Nigel Jarrett was on hand at St David’s Hall to take in a performance of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 3 in D Minor by the Prague Symphony Orchestra.

Embracing the world and its wonders in a work of art today might be thought of as aggrandisement, self-aggrandisement if artists position themselves at the centre of things. Music, for instance, has moved on to constriction and particularity, dwelling on simplicity and detail (though it’s not always that simple). Minimalism was and is an antithesis of the gargantuan as represented by Mahler’s Third Symphony and other late-Romantic works. But the Mahler revival in the 1960s coincided with the Cold War and its threat of universal extinction. Maybe it continues fifty years on because the threat is of a different order, or is simply compounded by environmental disasters. Maybe ‘thinking big’ will be our only salvation.

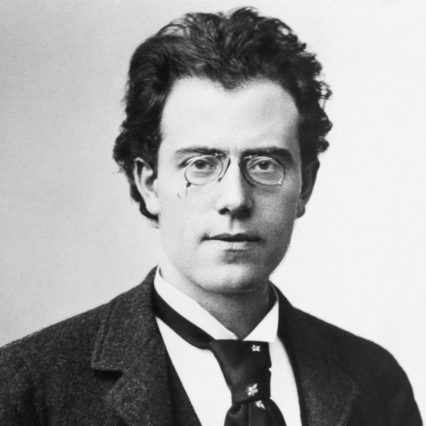

Taking Mahler’s Third as inspiration, however, is stalled by the composer’s decision to disguise its allusion to ‘real’, everyday scenes and events, to what in his world is vulnerable to loss. So-called ‘programme’ music, which tells a story, is often considered inferior to ‘absolute’ music, which has its own form, life, meaning and relevance uttered in a purely musical language. That said, Mahler did offer literary-philosophical clues to what the Third represents. But however you describe it, the prominent feature of a symphony that lasts more than ninety minutes is its length and whether or not the longevity is justified. The last thing such a gesture requires is a discreetly hidden yawn. Mahler’s ideas of what a symphony should be about were confided to Sibelius when the Finnish composer had pared his view of form and content, though it was not a limiting exercise in terms of an inclusive world view.

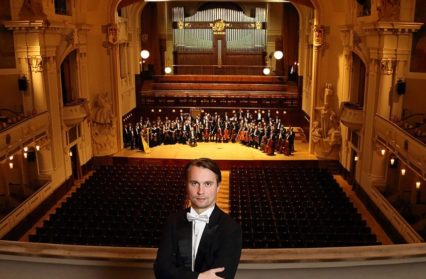

It’s a Finn, Pietari Inkinen, who as its chief conductor, has brought the Prague Symphony Orchestra and Mahler’s Third on a tour of Britain. The trip has meant employing local choristers to sing the vocal parts of the symphony at each venue. This is some undertaking, particularly when the choir is combined, as on this occasion: two from Cardiff and one from Swansea. For someone who next year will conduct Wagner’s The Ring cycle at Bayreuth, the prospect probably held little trepidation. The Cardiff vocal forces scarce slipped on a cue but more of them might have made a more significant sound: Inkinen could have done little about it on the night. This was a pity, because his orchestra, at full complement, had the measure of the work’s breadth and distance.

Not the least of his achievements was to suggest that the huge first movement was not the end of matters but the beginning. That Mahler composed it last is a mighty paradox. Inkinen’s interpretation of this opening, like the score, concentrated on brass, winds and percussion to depict the rolling-out of life and nature themselves and their manifestation as something ever-advancing and blossoming. It’s a patchwork of marches and fanfares. That it should not exhaust its audience underlines its importance as the base of a pyramid, on which subsequent movements stand less bulky and more delicately transparent. Inkinen allowed time after it for everyone to re-group, and his second movement, Mahler’s symbolic moment ‘when the creation cannot speak a word or make a sound’, was a delight, the high strings in particular and the pizzicato basses evoking a flower meadow, all aflutter in the warm air. The third movement, with its distant ‘posthorn’ (principal trumpet Marek Zvolánek) and its military-band simulacra, was not entirely successful. The hall’s acoustic-only ever becomes a problem when multitudinous orchestral forces are on stage as here. The trumpet was not so much a few furlongs away as in the garden next door, so to speak. Heads in the audience turned to find out where at the back of the auditorium it was. Whatever the location, it was sonically far too ‘forward’. As an antidote, the leader for the evening, Hiroko Takahashi, had played her embedded solo passages with feeling and a sense of belonging.

Balance was also a problem later, though it was restored in the fourth movement, a setting for contralto of lines from Nietzsche’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, delivered with a fine sense of space and rich colouring by the Czech mezzo Ester Pavlů. Inkinen’s tempi were such that the text’s short phrases were uttered and left in space, denoting the isolation Mahler intended. This is Nachtmusik, ending in warm lyricism. The fifth movement is where almost unnoticed the singer is joined by the choir, and in this case, where its small numbers showed and the separation of continuity between the women’s voices and the children’s (their ‘Bimm, bamm, bimm, bamm’ of the bells) to achieve Mahler’s antiphony did not work. This is also, therefore, where using local forces without time for proper integration left the choir to its own devices, when in fact there is the subtlety of utterance to be observed and rehearsed.

Inkenen quite rightly saw the sixth and final movement as a height to be scaled, from which the foregoing material, programmatic or purely musical, could be viewed. It is triumphant of the work’s evolution and, if you are so convinced, of the power of love. It’s where even the composer’s descriptions of pure sound start to become problematic and even of little use, that final bashing duo of timpanists no longer vindicated by score markings but providing the kind of finale that Minimalists might smile at when not stifling a yawn. But one of Mahler’s bequests has been to mingle low and high art (those military marches and elevated concepts), and composers are still fretting over them.

The Prague Symphony Orchestra has a website if you would like to stay updated on their future performances.

Nigel Jarrett is a former newspaperman. He is a winner of the Rhys Davies prize and the Templar Shorts award for short stories and is represented in the Library of Wales’s anthology of 20th–and 21st-century short fiction. He’s also written a poetry collection and two volumes of stories. Among others, he writes for an Acumen poetry magazine, Jazz Journal, and on music and other subjects for the Wales Arts Review. His pamphlet of stories, A Gloucester Trilogy, has just been published by Templar Press.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.