In the first of a new series of short stories highlighting the rich history and contemporary work in the form being done by Welsh publishers, we bring you a story from the new collection by the late Norman Schwenk, “Miss Cross” from Miss Cross and Other Stories (Parthian).

‘Vera, take the children to the story corner, please, and keep them away from the windows. Give me 10 minutes.’ Miss Cross was whispering – unusual for her. She taught the children never to whisper, and she was the kind of head teacher who led by example.

Vera had enough experience not to dither or flap, just to do it. She caught the note of disciplined alarm in her young boss’s voice, and knew she did not panic for nothing. Miss Cross took one more look out the window and headed for the door. She had to work quickly. In half an hour the children would be going home, and in ten or fifteen minutes mothers and fathers would be assembling to pick them up. She walked swiftly round the corner of the school, through the gate and onto the grass verge by the school-crossing. She stood for a moment and stared at the small, inchoate mound of grey fur mashed onto the tarmac. Someone’s pet. Tears made her eyes itch, and a solid knot formed in her throat. She remembered her little mongrel, Pearl, who had been run over when she was ten. Miss Cross took a deep breath and tried to think.

Cars swished past in that unrelenting way traffic has. Some drivers slowed to glance at the small woman standing there, since she looked about to cross: a few men paused to gawp because she was a bit of all right, but none noticed the lump of matted hair that fixed her attention.

Miss Cross had just passed an exasperating half hour phoning round to council services – everything from Police to Fire, Cleansing to Animal Shelter – hoping to find someone who would come quickly and clear away poor Dusty or Pepsi, whatever the name was on the bent metal tag just visible in the fur. Cleansing had promised to come tomorrow. Too late. No one seemed to understand the distress that would overwhelm some of her little charges when they stepped onto the crossing and saw the tiny, mangled corpse. In the distance Miss Cross could see Brenda, the lollipop lady, on her way to mind the crossing. This focussed her thoughts. Brenda was certain to be unhelpful, and she had a knack for making you feel everything was your fault.

Miss Cross marched round to the back of the school, took out her heavy ring of keys and unlocked the cupboard where the tools were stored. The scoop shovel was long gone, stolen in one of the frequent raids on the school – the police regularly called her out in the depths of night – but there was still a venerable spade with a broken handle. Tooled up with spade and black plastic bin bag, she walked round to the front again and walked onto the crossing, stopping the honking traffic. Brenda had arrived by now, as a mute, baleful witness.

‘It’s good there’s no blood,’ thought Miss Cross. She ignored the gaping drivers who crawled past – one actually whistled as she bent over – and studied how best to approach the task. At first, squinting from the school window, she thought it might have been a cat, but close up she was now sure, from the texture of the tail, which was still intact, that it had recently been a dog. There was no address or phone number on the tag, and she could not read the name, which had been scratched on by hand.

Miss Cross positioned one foot on the bag so it would not blow away, then slid the spade along the tarmac until the small body was more or less balanced on the blade. She marvelled at the construction of bodies. How could one, squashed so flat and so completely floppy, somehow keep its shape? Even the little head was flattened. It dangled off the spade on the end of a broken neck. At this point the reasonable thing would have been to ask Brenda to hold the bag for her. She could just hear Brenda say, ‘Nothing to do with me,’ her favourite phrase. Now, holding the bag with her left hand, she negotiated the spade with her right and, with a single deft movement, as if she had been shovelling cadavers all her life, popped it in and out of sight. The grace of this manoeuvre surprised even Miss Cross. There was a greasy spot where the body had lain, which looked both slippery and sticky. She took a tissue out of her sleeve and wiped it round to little effect. Then she straightened up and tied the top of the bag, swallowing a small spurt of vomit which had risen to her mouth. Finally, disciplining herself not to glare at Brenda, she left the public arena of the crossing, walked briskly round the back, leaned against a wall and pondered what to do next.

A proper grave was out of the question. The nursery school ground had been covered almost entirely in plastic cushion, and the children were certain to spot anything unusual. It would have to go into one of the giant steel wheelie bins in front of her. She stepped up to one, raised the cover and looked in. A stale, unidentifiable stench wafted over her as she peered in trying to see the bottom. How on earth did the cleaners manage? The bins were efficiently designed for emptying into council lorries, but awkward to handle for human beings. The cover alone seemed to weigh a ton. Her sad parcel hit the bottom with a soft splash. Miss Cross exhaled profoundly, then took her anger out on the old spade, slinging it back in the cupboard and slamming the door like a sheriff jailing a bandit. As she walked round the front she remembered the dead dog story that was part of family legend. A favourite aunt of hers had woken one morning to discover her little old dog had died in the night. The aunt lived in a block of flats in London and couldn’t bear to put the body out with rubbish. She decided to take it back to the family farm and bury it there. So she packed it in a suitcase and went straight to the railway station. A nice man at the station offered to help with her heavy suitcase, but while she was buying a ticket the nice man ran off. She was left to imagine the horrors of what might have happened to the body of her pet. Her only consolation was to imagine also the look on the thief’s face when he opened her suitcase.

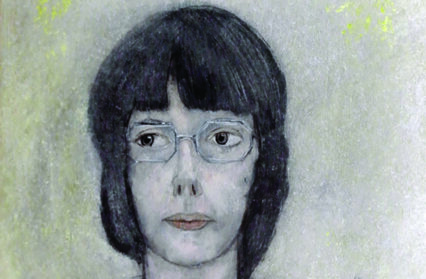

Inside the school you’d never have known there was an emergency. Blessed Vera was coping. The children were clearly enjoying their extended version of ‘Gelert’, the tragic tale of the heroically faithful dog. Miss Cross spotted little Rosie Todd, with her thick glasses and cross-eyes, her face shining. She wondered how Rosie, so proud and sensitive, would have dealt with seeing the body in the road.

But when Miss Cross glanced out the window again she spotted Brenda marching toward the school, holding her lollipop like a pikestaff at the ready. What could have induced Brenda to leave her post? Shuffling beside her was a crumpled woman with a puffy red face who carried a large box of tissues. Miss Cross nipped over to the entrance and managed to head them off.

‘What is it, Brenda?’ she said, standing with her back to the door.

‘This is my friend, Pat,’ announced Brenda. ‘The police say you’ve got her dog.’

Miss Cross noticed their conversation was already attracting attention. A few mothers and fathers had gathered at the fence. She could imagine the questions at tomorrow’s parents’ evening.

‘Brenda, I think you’d better go back to your crossing,’ she said. ‘Pat, I’m Rebecca. We can talk in my office.’

Brenda opened her mouth to speak, but Miss Cross gave her a look; Brenda did an about-face and retreated.

Miss Cross led Pat to her office, where she explained about the dog on the crossing as gently as she could. Her remarks were punctuated by ripping sounds and toots as Pat removed tissues from the box, mopped her tears and blew her nose. Pat’s dog was Georgie, a small white poodle she was convinced had been stolen by dog thieves. She was maddeningly vague about his collar and tag. Miss Cross had to admit the dog on the crossing could once have been a white poodle. If she pressed Pat for more complete information, though, it seemed to make her cry even louder, so she promised to bring the body in where Pat could have a look. She didn’t say it was dumped in a wheelie bin. As Miss Cross walked through the schoolroom on her way back to the bins, she noticed Vera was at the question-and-answer stage, winding up her story in preparation for the final song.

Little Mohammed Clark caught her eye, his upper lip as always shining with nasal slime; surely her efforts were worthwhile, saving him a nightmare or two – he was such a tender-hearted softie, who loved Miss Cross with utter devotion.

Back at the bins she struggled to remember which one she’d chucked the bag in. The smell was no help. They all had the same unrecognisably foul odour, one that didn’t make you jump with revulsion but drove you back slowly. She stood on tiptoe – as a career woman she had to contend with the handicap of being petite as well as pretty – and peered in the middle bin. She saw lots of black bags, and there it was; she was quite certain, even though all the bags looked very much the same. She got a rickety stepladder out of the cupboard, together with a grizzled old floor brush, climbed up and threw back the huge lid, which sheared off its hinge and fell to the concrete with a crash. Miss Cross stopped and listened. She could hear the children singing ‘She’ll Be Coming Round the Mountain’. They always had a song at the end of the day – nice for the parents while they were waiting. She started fishing with the brush, trying to hoist the bag up where she could catch hold of it. This didn’t work. The bags were slippery from a pool of rancid water at the bottom. She then laid the brush across the top of the bin so she could grip it like an acrobat, reaching down with her short arms and groping with her small hands. Just as she touched the chosen bag, she teetered on the stepladder, overbalanced and pitched in head first.

Anyone peering around the corner of the school at this moment, as indeed Brenda was, would have seen a slim set of ankles and a neat pair of beige court shoes waggling just above the rim of the bin. Miss Cross had landed on the layer of bags and was not injured, though she would nurse a painful shoulder for a few days, and a sore nose where the brush had struck her. She stood up inside the bin, wiped off her neat brown suit, readjusted the scarf round her throat and ascertained that her tights were well-laddered. She checked an impulse to tears, holding her breath and swallowing hard. Then she picked up the bag she’d been angling for and opened it. All-purpose trash. God help me if I’m in the wrong bin, she said almost out loud. (What she did say out loud was, ‘balls’.) A quick rummage produced the right bag, though, and Miss Cross dropped it over the side along with her shoes and started struggling to climb out. She could feel hysteria rising in her and concentrated hard on practical things. She made a pedestal of bags, threw one shapely leg over the rim, then the other and slid down onto the concrete. As she did she noted Brenda spying on her round the corner. Brenda had traffic backed up for a hundred yards or more, because standing out on the crossing gave her the best view. Then, seeing that Miss Cross saw her, she resumed conscientious lollipop duty. Miss Cross had just got her shoes back on when a worried Vera appeared and asked, please, would she come and deal with some council workmen who said she’d phoned them. They were causing a ruction. Miss Cross, bag in hand, was confronted at the school door by two men wearing wheel-clamp-yellow council jackets that said CLEANSING. One was large and burly, the other small and scrawny.

‘Where’s the dead dog!’ shouted the big one, so everyone could hear. Parents and children were milling around putting coats on.

‘We were called here on emergency,’ said the little one. ‘Dead dog on the crossing.’ Miss Cross didn’t dare look at the children, but she could sense their agitation, like a kettle starting to boil. She opened her mouth to speak to the workmen and felt the bag snatched out of her hand. Behind her the pathetic Pat was untying the bag so as to display its contents to the massed gathering. Miss Cross tried to snatch the bag back and there was an unseemly grapple. ‘Please! Let’s open it in my office,’ hissed Miss Cross. ‘You’re upsetting the children.’

Pat burst into sobs, still clutching the bag.

‘Is that the dead dog?’ shouted the burly workman.

Miss Cross turned on him. ‘I’ve cleaned the crossing myself,’ she said. ‘You’re too late. Now please go.’

‘So who’s going to sign our job sheet?’ said the scrawny one. ‘You’ve wasted our time.’

Miss Cross scrawled on the proffered job sheet and turned her back on the men, only to behold Pat, surrounded by children, opening the bag. As the dab of dead fluff came into view there was a chorus of wails, followed by tears and general chaos. Vera was doing her best to shepherd children out the door and match them up with the right parents.

‘Miss Cross!’ She could hear the grating voice of Ms Viner at her elbow, a parent who never missed a chance to complain. ‘Miss Cross, I must protest. This is outrageous.’

Miss Cross turned to Ms Viner and looked her in the eye until Ms Viner looked away. She noticed Ms Viner had a bright yellow spot on the end of her nose, which seemed sufficient revenge for the day and helped Miss Cross resist an impulse to kick her in the shins.

‘I’ll explain at the parents’ evening tomorrow night,’ she said, her voice even and smooth. ‘Now please excuse me.’ Small as she was, Miss Cross gathered up Pat and the bag, hauled them into her office and shut the door on the noise. She started to give Pat a telling off but didn’t have the heart and ended up comforting her.

‘Sorry, Rebecca,’ Pat kept saying. ‘I’ve caused you such trouble. You’ve been so good.’

‘It’s your little dog, is it?’ said Mrs Cross. ‘Georgie?’

‘No, it isn’t,’ Pat blubbered. ‘Nothing like him.’

A small explosion of rage detonated inside Miss Cross, but there was not a flicker of an outward sign. Just then Rosie Todd’s father barged into the office without knocking, clearly upset. Oh, no, thought Miss Cross, I’m losing even the supportive ones. His voice trembled as he spoke.

‘Miss Cross, can you please explain why my child was handed over to me in tears? What is going on in this school of yours?’

‘I do apologise, Mr Todd. I can’t discuss it now. I’ll make an announcement at parents’ evening.’

Mr Todd hesitated. ‘I’m afraid that’s all I can say for now.’ She indicated the weeping Pat, glad to be able to use her as an excuse.

‘Very well,’ said Mr Todd, who left in confusion.

Pat started sobbing even louder, going on about what trouble she’d caused and how kind Miss Cross was. Stonily, Miss Cross left her to it and went to help Vera clear up. Before long Brenda arrived to collect her friend, and they limped away, Brenda helping Pat down the path as if she’d broken a leg.

Before Vera went home Miss Cross apologised for not keeping her better informed about the dog. Vera shrugged and laughed – not a nervous laugh, but a loud, genuine, Vera laugh.

‘I loved it when you sent those council blokes packing,’ said Vera. ‘We’ll talk to the kids about it tomorrow. They’ll understand.’

‘Yes,’ said Miss Cross. ‘And the parents.’ Her heart sank at the thought.

‘I know you well enough to do some grooming, don’t I?’ said Vera unexpectedly, and reached over and touched Miss Cross’s shoulder. Then Vera held out her hand and laughed again. In her palm was what looked like a large sprig of parsley.

‘A bit of garnish from round the back, I expect,’ said Vera.

After Vera had gone Miss Cross stood alone looking out the window, all her nerves singing, waiting for calm to return. Maybe they ought to have a burial tomorrow. Would it be wise? Some of the parents would protest, perhaps quite rightly. But now that they had all seen the dead dog? She couldn’t say it had gone out with the garbage. Just then, over the crossing and up the path to the school, shambled a pleasant-looking young man in scruffy clothes. His body was deformed in some way, but Miss Cross couldn’t quite make out how. She went to the door to meet him.

‘Sorry to trouble you,’ he said, in a warm, dry voice. ‘The police say you might have the remains of my dog, Bandy. He got out this morning. My fault. He hasn’t a clue about cars.’

Miss Cross sighed and smiled. ‘The police seem to think I run a canine morgue,’ she said. ‘You’re welcome to have a look. I’m afraid the body’s in a rubbish bag.’

‘He’s white, with a black band round the base of his tail,’ said the man. ‘Like a napkin ring.’

She went into her office and got the bag out of the desk drawer where she’d stowed it while placating Pat. The man looked inside. Miss Cross noticed he used only one hand.

‘That’s Bandy,’ he said, swallowing. ‘Poor little sod.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Miss Cross. ‘I’m so sorry.’

‘Thanks,’ said the man. They stood facing each other, the young man choked with feeling. Miss Cross could now see he had only one arm. He knelt beside the bag.

‘Is he going to pray?’ she thought. ‘Should I kneel too?’

With his one arm the man reached inside the sleeve of the other. There was a small whirring sound, and a prosthetic arm slowly reeled out of the sleeve and grasped the top of the bag. The arm was a complicated structure which looked like it might have been made from antique toys. The man looked up and smiled. ‘Like it?’ he said. ‘I made it myself.’

Miss Cross gaped at him, speechless, and smiled weakly. He hooked the bag onto the mechanical arm, shook her hand with the other and went out. Miss Cross started to snicker hysterically, but controlled herself. Then quietly she began to cry.

***

Norman Schwenk (1935-2023) was a writer and teacher from Lincoln, Nebraska in the United States. A love of reading and writing poems infused his childhood and intending to work as a teacher, he took a first degree at Nebraska Wesleyan University, and then enrolled as a postgraduate in American Studies at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where he was made a teaching and research assistant in English. In 1960 he won a Fulbright Award from the U.S. State Department, and for the next five years he was a Fulbright Lecturer in English at Uppsala University in Sweden. He moved to Wales in 1965, having been appointed lecturer in American Literature at Cardiff University. He later became head of a thriving creative writing programme developing and influencing a diverse group of many talents.

Love and mortality were enduring themes for Schwenk including his fine collection The Black Goddess (1990) through to his selected poems in 2016. He also had a playful side to writing which included a series of chapbooks of comic verse exploring popular forms including How To Pronounce Welsh Place Names, a collection of limericks.