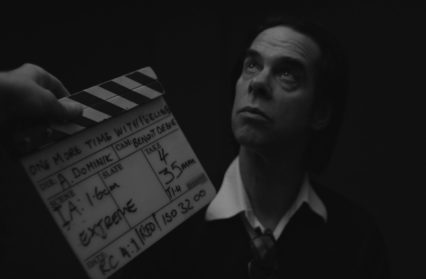

Poet and Young People’s Laureate Sophie McKeand on the heart-breaking documentary accompanying the new album from Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – One More Time With Feeling.

One More Time With Feeling is, in Nick Cave’s own words, a film about change. What director Andrew Dominik also beautifully and poignantly illustrates is how change doesn’t just sneak into your house, help itself to the last of your favourite food and rearrange the furniture. Apocalyptic change like that experienced by Cave over the death of his teenage son, Arthur, will barrel through the door, raze the house to the ground with you in it then blow the ashes to the wind. Your belief in the linear narrative of the stories you tell yourself is thoroughly decimated before being scattered across the ocean of time (or desert if you prefer), with past, present and future waves indistinguishable from one another.

Cataclysmic change strips a person of any sense of identity or purpose. Time becomes (to paraphrase Cave) like a piece of elastic you stretch out, before it snaps back to that one moment. Cave’s usually commanding voice is uncertain and wavers as his mouth struggles to explain his epiphany that time is everywhere and all of it is happening right now.

This is not a new concept, the circularity and ubiquity of time is central to many indigenous belief systems including Aboriginal Dreamtime, as well as Taoist philosophy, and in more recent years western writers as diverse as Terry Pratchett (Thief of Time, amongst other books) and Jay Griffiths (Pip Pip, A Sideways Look At Time) have analysed the possible shape and form of time. I created the long poem, Coflyfr: experimentations with time in an attempt to continue this exploration, with some limited success.

What is apparent with Cave (and has been for a variety of people, myself included) is that it can often take a huge mental, spiritual and/or emotional upheaval to rupture our western, patriarchal perspective of time and open our eyes to its more female, circular, fluid nature. And when we, as artists, are left at this point in no-time-time, with the knowledge that none of it works in the way we’d always believed, that really we are all just tiny boats cast adrift, bobbing around the vast ocean of past, present and future, it becomes difficult to continue creating work as an outdated linear fairytale.

The interviewer questions why Cave’s latest work lacks the narrative storytelling of previous songs, to which Cave replies that linear structure is something he needed in the ‘time before’, and we realise that now this new perspective has been gained nothing can ever be the same.

Moving into the past for a moment, I’m convinced everybody who knows Nick Cave’s music has had the lightbulb moment. That one track or album when his work burrows itself so deep into the subconscious you can do nothing less than kneel at the altar of his genius.

For me it was And No More Shall We Part, which will signal to Nick Cave die-hard readers that I’m pretty much a lightweight – And No More being the eleventh studio album from Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds – but I found it utterly compelling and played it relentlessly (still do). To use words like haunting, captivating or heart-wrenchingly beautiful does it no justice at all.

The first time I saw Nick Cave live was on 5th May 2008 at the Birmingham Academy for the Dig, Lazarus Dig!!! tour. The energy, the swagger, the heat, the handlebar moustache, the words tumbling from his mouth like prophecies as he grandstanded his way through an entire set like a preacher man on a mission, were overwhelming. The room was so tightly packed I ended up crouched on a shelf, back pressed against a hot damp ceiling. This gig was a revelation, an epiphany, a realisation that Nick Cave embodies every song, every character he writes about. I understood at that moment what it is to live your art.

The 2014 film 20,000 Days On Earth continued blurring the boundaries between biography and story, wrapping the narrative around objects from Cave’s past that were used as cornerstones of truth. Surrounded by various cameo appearances from the likes of pop legend Kylie Minogue, Cave strides through the entire film with his trademark eloquence, dark humour and confidence.

Returning to One More Time, what this film does, apart from showcase songs from the stunning new album Skeleton Tree, is unfold a new chapter of Cave’s creativity forced upon our protagonist by his recent bereavement, and he is clearly floundering in the aftermath. Arthur’s absence expands at times to fill the film to almost claustrophobic levels, with the hesitations and uncertainties in Cave’s speech creating unexpected and jarring voids that the audience cannot help be sucked into.

It is difficult to watch Cave, usually so poised and expressive, stare at the bags under his eyes in a mirror and fail to relay his dismay other than to point out the obvious and shrug. I’m choked writing this. Cave’s well-worn swagger and crown have been stripped from him to be replaced with a head of thorns and a mouth of ash. And this is the thing I need to repeat, watching someone so articulate be so, inarticulate, is more than difficult. Speaking with friends afterwards we were all put through the wringer by the experience. One said they felt as though they’d been to a funeral – which perhaps we had, of sorts.

Please don’t let this put you off. One More Time With Feeling is an intense, beautifully shot, minimal film, incandescent with Cave’s stunning new tracks. It is deftly edited and avoids falling into the usual tropes of sentimentality, pity-seeking or resolution. Arthur’s death is not mentioned until the very end, but there is no escaping the effect this trauma is having on Cave, Susie (the wife he so openly adores) and Arthur’s twin brother, Earl. No matter how little he is mentioned, Arthur’s presence, and absence, are inextricably stitched throughout this film and the accompanying album.

One More Time With Feeling

Writer’s note: We saw One More Time With Feeling at a great, local(ish) community cinema called Kinokulture just over the border in Oswestry. I need to firstly shamefacedly admit to never visiting before and secondly, sing its praises. It’s a CIC (community interest company) run predominantly by volunteers and is a wonderful place to have a beer or coffee before any of the films regularly on offer.