An opera by Leŏs Janáček

Libretto after Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Notes from the House of the Dead

Welsh National Opera

Conductor: Tomáš Hanus

Director: David Pountney

Designer: Maria Björnson

Lighting Designer: Chris Ellis

Revival: First performance using new critical edition by John Tyrrell and Charles Mackerras

Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff, 8th October 2017

In the video projected onto the set at the opening of this production the great eagle turns its gaze on the audience in a way which immediately inspires compassion, for its own life and for human life. And this encapsulates the Czech composer Janáček’s final work, the three-act opera From the House of the Dead, found on his desk after his death in 1928. Wrongly thought at that time to be unfinished because of its extraordinarily sparse textures, and subsequently elaborated by well-meaning contemporaries, it has now been restored to the form that – as far as we know – the composer intended.

Sadly, Charles Mackerras himself died before he had the opportunity to hear the final result of what he had worked on with the musicologist John Tyrrell. We have Mackerras to thank for bringing the music of Janáček to British audiences at all. The composer’s work is now part of the regular repertoire of the opera houses, but it is 20 years since this production of From the House of the Dead was last performed by WNO. The design, created for the original 1982 co-production with Scottish Opera by Maria Björnson, remains fresh visually. When Björnson died in 2002, David Jays wrote in her obituary in The Guardian:

“Her designs were lavish but unsettling, as she perfected a unique idiom of romantic expressionism. Her sets often functioned as magnificently haunted cages.”

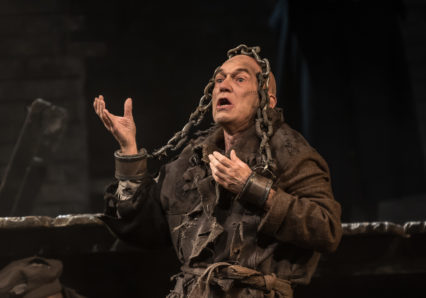

The set for this production is indeed so. The action takes place in a Siberian prison camp – akin to the one where Dostoyevsky was himself incarcerated – where prisoners are effectively entombed. The men work, sleep, tell their stories and, occasionally, entertain one another and a few inscrutable visitors. Most of the time they are shackled, the sounds of their irons ever-echoing, themselves a part of the music. The chance of freedom is rare and apparently random, but there is always hope. The wounded ‘Eagle Tsar of all the forests’ is imprisoned there too. The image of the bird trying to fly away recurs in the opera and the prisoners raise their shackled arms in imitation of the action.

Within the mass of the prisoners all are nonetheless individuals. The structure of the opera is, both musically and dramatically, cellular. What we see on stage is a collage, an ever-turning composite image in which different elements are momentarily highlighted at different times, literally so in Chris Ellis’s brilliant lighting design. Against the backdrop of the grinding round of heavy work there are human interactions, recounted or portrayed. Most are brutal. Several of the men who tell their stories have committed murders. But Janáček refuses to despair over this. The autograph on his score reads ‘In every creature a spark of God.’

Janáček’s music for From the House of Dead contains extremes of texture and harmony. By leaving yawning gaps between treble and bass he creates an emotional maelstrom from which, as a listener, you are not set free until, at the end of the opera, the eagle flies once more, watched by all the prisoners.

This is an ensemble piece, but if there is a star in this production it is the WNO orchestra, conducted with tremendous energy and sympathy by Tomáš Hanus, himself a Czech who grew up in the town of Brno where Janáček lived, and who has championed his music. There are parts of the opera, particularly during the entertainments which the prisoners put on, when there is very little or no singing, and the orchestra comes to the fore. In the music here we hear swirls of folk melodies, a comforting lyricism so that briefly we, with the watchers on stage, can laugh at the grand guignol of the devils with pigs’ heads and the innocent knockabout in the pantomine. ‘What good actors,’ sings the Tartar boy Alyeya as he drinks tea with his protector, the political prisoner Goryanchikov. But the mood changes abruptly as real violence breaks out again, the innocent Alyeya is injured and drum rolls announce a crackdown by the prison warders.

In the sung sections Janáček’s use of speech rhythms in his music defines and differentiates his characters. Of course he was writing for the rhythms of Czech, not English, which surely presented particular challenges both to David Pountney as translator and to John Tyrrell and Charles Mackerras as editors. The decision to perform an English translation is understandable, given difficulties for both singers and listeners, but we are inevitably some way away from hearing the tone colours that were in Janáček’s mind.

Nevertheless, this is a production of great intensity and its sounds and images linger in the mind. Amongst a strong cast Simon Bailey, as Shishkov, gives a powerfully-sustained performance in the long and awful story of his life, which ends with a dramatic revelation. The sure-voiced story tellers also include Alan Oke as Skuratov, Mark Le Brocq as Luka and, in a perfectly-judged cameo, Adrian Thompson as the unfortunately big-eared Shapkin. Paula Greenwood, taking the soprano role of the boy Alyeya, is convincing, and her cries of ‘You are my father’ to Ben McTeer as her protector Goryanchikov are heart-rending – for he is to be released and she must stay on in the brutalised environment of the prison.

Janáček’s music is masterful in its portrayal of the shifting moods among the prisoners. At the end of the opera hope soars as the eagle flies free, but the men must go back to work; the orchestra falls silent as they turn to continue on their relentless shackled cycle.

Performances of From the House of the Dead continue within WNO’s Russian Revolution Season, part of R17 across Wales.

Read Steph Power’s conversation with David Pountney about Musorgsky, Janáček and more.

Cath Barton, a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review, is an English writer who lives in Wales. She won the New Welsh Writing AmeriCymru Prize for the Novella for The Plankton Collector, which will be published in 2018 by New Welsh Review under their Rarebyte imprint.

Header photo credit Clive Barda/ArenaPAL

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.