Ben Woolhead spoke to photographer Robin Weaver about his new book focusing on Wales in the 1970s.

‘In school we’re taught about kings and queens,’ observed Paul Wright in a recent interview with the Manchester Evening News. ‘I want to hear the story of the girl on the checkout in the supermarket. … I want to celebrate the everyday lives of everyday people.’ Little wonder, then, that the British Culture Archive – the rich photographic resource founded by Wright to do precisely that – has previously showcased the work of Robin Weaver.

Weaver recalls first becoming fascinated by photography as a child, handling pictures taken back in the 1920s by a grandfather he never knew and realising that he was holding ‘a piece of history’. For someone who marvels at photography’s ability ‘to freeze a moment in time’, it’s not hard to understand why subsequently discovering Henri Cartier-Bresson’s pictures was a profoundly revelatory experience: ‘It inspired me to see how he photographed people in ordinary situations and was able to find moments and create compositions in which he found amazing beauty. Some of his best photographs are like a ballet in which the subjects are frozen together in perfect harmony. I wanted to take photographs like this; to find the extraordinary in the ordinary.’

This passionate pursuit led Weaver to enrol on a three-year course at Newport College of Art, but formal education proved to be something of a disappointment. Learning about theory and the art of processing was useful, he admits, but the prosaic practicalities of life as a professional – ‘the actual business of promoting yourself and making a living’, for instance – were barely covered. In any case, Weaver suggests, photographers are born not made: ‘I think good photographers have a natural eye and instinct for composition which can’t be taught. I don’t think about rules when I’m taking photographs. It’s an instinctive feeling and I just know when it looks right. If you think it looks right, it probably is – press the button.’

After leaving college, Weaver found work as a staff photographer for the South Wales Argus in Newport, but soon felt trapped by the rigid constraints of the trade and the format, itching for greater freedom and spontaneity: ‘The newspaper style was to have people looking at the camera, posed in set-up situations or groups. I relished the rare actual news situations when I could just photograph things as they happened. I always carried my own small Leica in my bag and I would pull it out when I could see a photograph I could take for myself in my style. I also spent a lot of time travelling around the South Wales Valleys in search of people, events and situations which interested me. I never really asked myself why, it was a compulsion to record life around me.’

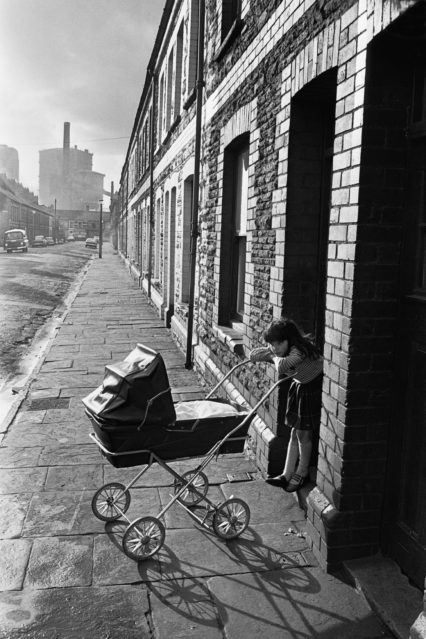

The resulting images would have forever remained personal, private mementoes of a particular time and place, had Weaver not gone back to the negatives many years later and decided to present them together in a self-published book. A Different Country appeared in 2015, and now Café Royal Books – whose admirable business model involves putting out a new limited edition book every week, each one showcasing the best in post-war British documentary photography, limited to 250 copies and available for the price of little more than a pint – have published a smaller selection of the pictures under the title South Wales in the 1970s. Those who feature in them are not ‘kings and queens’ but Wright’s ‘everyday people’: men walking up and down steep Valleys streets; a couple of women chatting in front of condemned houses in Tiger Bay; a girl minding a pram on a terraced Splott street that recedes away into the distance towards the ghostly shadow of the imposing East Moors Steelworks. Neither artificially posed nor taken to illustrate particular news stories, the unfiltered and unvarnished images give an invaluable insight into working-class lives and culture in the region at the time.

Weaver pitched the idea for South Wales in the 1970s to Café Royal’s Craig Atkinson but was happy to leave the publisher to choose which images to include. Of those that Atkinson selected, Weaver’s favourite, taken in a Splott corner shop in 1974, has everything that he admires in Cartier-Bresson’s best work: ‘I like the composition which is almost symmetrical with the door in the centre and the perspective of the counters leading to it, the people off-centre. But mostly because it’s a great moment caught. The child is handing over her money with such a joyful look on her face, the dog is scratching. And there’s so much nostalgic detail to find – the old-fashioned bottles of milk, the bacon slicer, jars of sweets, the poster on the door, the girl’s wellies.’ He’s also very fond of a picture of bow-tied brass band members relaxing on the grass after the 1978 Miners’ Gala in Cardiff, while children in their Sunday best play chase in the background: ‘It’s the sort of photo I love where you think “What’s going on here?” and all the clues are there if you look.’

In many ways, that image is typical of the whole collection. Much like the Martin Parr exhibition currently on display at the National Museum, the photos in South Wales in the 1970s generally show people at play rather than at work and skirt around politics – the obvious (and thus slightly jarring) exception being the picture of stony-faced Ebbw Vale steelworkers learning that they are to lose their livelihoods. ‘As a local press photographer I would naturally be sent to situations where people were having fun at events,’ Weaver explains.

Not that he shied away from depicting the grim realities of urban decay. Even then, though, like those of fellow Newport College of Art alumnus Tish Murtha in her posthumously published book Elswick Kids, his pictures of children standing smiling atop wrecked cars and imaginatively transforming rubble-strewn wastelands into playgrounds say more about the resilience and irrepressible joie de vivre of youth. ‘A sense of community was very strong in those places,’ he says, ‘and with less stress of modern life, they may even have been happier than now.’ Paul Wright has described the British Culture Archive’s mission as being ‘about highlighting diversity and community spirit as a way of bringing people together’; Weaver’s pictures of raucous parades, anti-racism marches and elderly Rhondda neighbours in matching patterned housecoats celebrate those same values.

Why capture these scenes in monochrome rather than in their full vibrant colour, though? Weaver’s reasons were both pragmatic and aesthetic: ‘All newspaper work was done in black and white at that time so it was the natural way to work. I had experimented with colour in college but it was expensive and I could easily process all my own black and white films and prints. Also, and this is something I still feel, with this sort of documentary work I think it looks better in black and white and that colour adds very little, possibly even detracts.’

Reflecting on the photos more than four decades after they were taken, he says, ‘I may have thought I was making a historic record but back then I couldn’t imagine how much the world would change.’ The Wales of the 1970s is metaphorically but also literally a different country for a photographer who for many years now has called England home. ‘It’s an ongoing project to revisit as many of the locations as I can, although, living in Derbyshire, I don’t get down to Wales as often as I’d like. The most striking difference I see in the valleys is the proliferation of trees. So many more trees everywhere as if nature is finally reclaiming the land now that the dirty industries of coal and steel have largely disappeared.’

Not only did Weaver leave Wales, for a time he also turned his back on documentary photography. Disillusioned with press work and what he calls ‘the constant “get-them-to-do-this” approach’, he found solace and succour in his new surroundings. ‘I have always loved the countryside, walking and climbing hills and mountains, and so I started taking landscapes seriously. Living on the edge of the Peak District was all the inspiration I needed. I found I could make good money from stock photography and lugged my Pentax 67 and tripod up many a mountain at dawn.’ These days, though, that enthusiasm for landscape photography is itself on the wane. ‘Since the advent of digital I return to those hills where once I was alone to find perhaps half a dozen photographers trying to get the same shot,’ he notes. ‘So, although I still do a lot and illustrate travel articles, I sometimes think “Does the world need another photo of this?” I find I’m coming full circle now I am retired and am more interested in the documentary side of photography.’

In the era of cameraphones, Weaver argues, we don’t just take too many pictures of the same landscapes and landmarks, we take too many pictures full stop – especially of ourselves: ‘What I don’t understand is the compulsion for people to take selfies all the time. I feel the world is full of narcissists. Today it almost seems as if people need to take photos to say “Yes, I’m here. I exist. I’m important.”’ It’s a phenomenon gently satirised in his ongoing project Snappers. Much better, he suggests, to flip the camera around and focus instead on the world you see around you. ‘Photograph what’s close to you,’ he urges. ‘There is magic around the corner. Also think about what is changing or could change. Document it before it’s too late.’

South Wales in the 1970s by Robin Weaver is available now from Cafe Royal Books