Frances Spurrier casts a critical eye over Boy Running, a new collection of poetry from poet and songwriter Paul Henry.

The collection is divided up into three sections: Studio Flat; Kicking the Stone; and Davy Blackrock. The first section deals with the poet finding himself alone again at the end of a failed marriage; the second section, increasingly elegiac in tone, follows a child kicking a stone around a town in 1960s Wales. The final section is based on and around the legend of Daffydd y Garreg Wen (David of the White Rock).

The collection is divided up into three sections: Studio Flat; Kicking the Stone; and Davy Blackrock. The first section deals with the poet finding himself alone again at the end of a failed marriage; the second section, increasingly elegiac in tone, follows a child kicking a stone around a town in 1960s Wales. The final section is based on and around the legend of Daffydd y Garreg Wen (David of the White Rock).

Some of the characters that weave their way in and out of the work, are, it seems humorous renditions of a new dystopian environment, some are ghosts; some feel as though they are ghosts still waiting for Rosie Probert.

Jones, Powell, Prosser, Price…

Her Closed sign means nothing to them.

They want to see themselves again

In Sunday best …

(Jo)

I first came across Paul Henry’s work when I saw his poem ‘Usk’ in a copy of Poetry Wales:

So we’ve moved out of the years.

I am finally back upstream.

And but for their holiday grins

On every bookcase the boys

Were never born, it was a dream.

This poem deservedly takes pride of place on the first page of the book. No matter how many times I read it, I am moved not only by its adroit technique but the breadth of emotional range and landscape evoked in three short stanzas.

The Usk flows lucidly through many of the pieces in the first section, with it’s ‘river’s griefs and joys’ (Jo) as do the flats, houses and rooms of the poet’s life, also the ‘lost’ voices of the poet’s sons.

And where are you, my sons?

I heard your voices in the bells

Of snowdrops, pulled by the wind.

(Studio Flat)

Many of the poems concern themselves with the idea that things which we believed were permanent in our lives turn out to be impermanent. The poem ‘Chattels’, for example, is an evocation of the fragmentary nature of permanence, the simple, broken bits and pieces we piece together in our lives to make a narrative.

The keys

Without furniture on the floor.

The standard lamp’s missing claw

The chattels of love, the chattels of war.

This theme continues into the second section Kicking the Stone. ‘In place of graves, front doors/name the neighbours’ as we follow through a Welsh town dressed in its 1969 garb. We make our own choices and live with them but somewhere the child that was us is still running, still kicking the stone around lost boyhood towns.

Children have an automatic edit function – or should I say memories have an automatic edit function when it comes to childhood – which does not allow for the presence of rain so there is often sunlight present in the second section, which is as it should be.

oh scuff of sunny dust

Preserve this woman’s song

Only the stone and I can hear

Up the unfinished road.

and

I must have taken pity on you,

Brought you home, kicked you

All the way up Penglais Hill

then into Maeshendre.

Where I kick you this minute

Between a skipping rope’s

First orbit of Wyn Kyffin

And its last, stone without end.

(Kicking the stone)

What is it about the land of lost content, the happy highways where we all, Housman style, can never come again? And why as poets do we seem to spend much of our time trying to do just that? More than just rose-tinted spectacles, perhaps the temptation is to expiate present pain by digging down far enough to a time when most of us were blissfully unaware of the difficulties which awaited adult lives.

Titles of collections are very important. Poet’s usually do their best to choose something which they feel comes close to encompassing an overall meaning for their work. This title reminded me of some lines spoken by Richard Harris playing King Arthur in the film, Camelot.

“Run, Tom, Run!” This line, spoken with all the considerable pathos which the actor Richard Harris was capable of projecting, sees King Arthur urge a young messenger boy called Tom to escape a battlefield; to survive. Living is better than dying and living to tell the world of the round table and its ideals, rather than stay and be killed by Arthur’s bastard son, Mordred, as the King himself would be, was deemed best of all. The film was of course based on T.H. Whyte’s famous novel The Once and Future King.

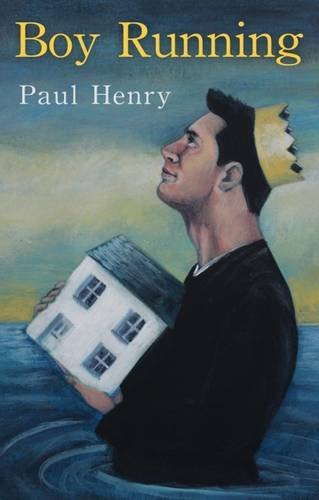

It wasn’t until Paul Henry’s book Boy Running landed on my desk that I realized how much those lines still resonate with me; although the cover artwork bears no resemblance to the scene, the title brought it back sharply into my memory. Somewhere, it seems to me, young Tom is still running, still trying to make Arthur’s vision a reality.

The poet’s own sons are seen :

My boys are coming back to me

Across the Glebelands pitches

Out of the echoey underpass

Leaving their childhoods behind

On the other side of the motorway

(Late Kick-off)

The first signs and signifiers of adulthood are great: freedom! Away from the restrictions and constrictions of being a legal minor; off to University; live; love; eat; whatever. But adult life erodes this narrative of freedom and so we seek to re-create it in poetic form. There is something about the lure and allure of memory, and particularly childhood memory; we are stalked by this small, innocent ghost of the used-to -be us. Being Welsh there are longings for places you thought you never wanted to see again. It’s called hiraeth.

This book is the stuff of survival, the stuff of mythology. For all that these poems may have arisen from personal suffering, they were born like Daffydd y Garreg Wen from a country of stone and song; a place where spirit is not bounded by the passing of time.

Boy Running is the finest collection of contemporary poetry I have read in years.

Boy Running is available from Seren Books.

Frances Spurrier is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.