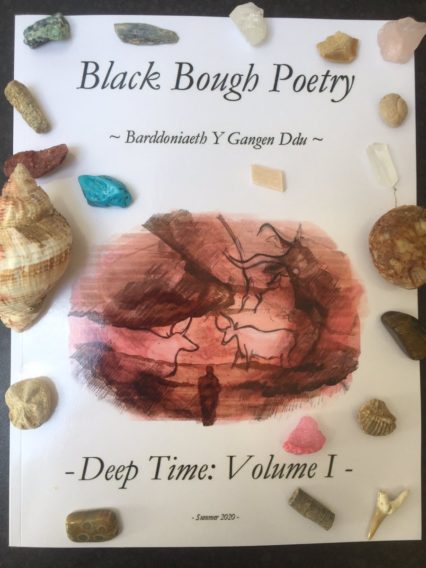

Thomas Tyrrell reviews Deep Time by Black Bough Poetry, the first volume of an anthology of geological poetry inspired by the work of Robert Macfarlane.

Geology is a museum cabinet full of wonderful words: malachite, Dalradian schists, gypsum, Karst. Stalagmites and stalactites. Then there’s the geological ages, Eocene, Silurian, Triassic, as magic and incantatory as the shipping forecast. Poets have delved into this wonderful word-hoard for decades, from Auden’s ‘In Praise of Limestone’ to the late work of Hugh MacDiarmid. Robert Macfarlane drew on it for Underland, a prose exploration of parts underground, and by direct inspiration from Macfarlane comes this first volume of Deep Time, an anthology of geological poetry. It is published under the aegis of Black Bough, a Swansea-based poetry publisher run by Matthew M. C. Smith. Their previous output, released free online, has been carefully themed broadsides of very short lyrics, beautifully illustrated. The careful theming returns here, and some of the illustrations, by London architect Rebecca Wainwright, are breathtakingly beautiful. The concision is less in evidence: their normal limit is ten lines, but a few poems here stretch to sixteen, or circumvent the requirement with long, Whitmanesque lines.

The title theme presents any poet with a challenge. Lyric poetry, intertwined with personal viewpoint and the writer’s emotions, is not the easiest medium in which to confront the fathomless abyss of deep time, in which the whole span of human existence is less than an eyeblink. From the opening poems, however, in which the poets reflect on the wall drawings of our primeval cave-dwelling ancestors, there’s more of an emphasis on connection than displacement. ‘Open Ocean’, by Clarissa Ackroyd, is one of the few to acknowledge the chasm.

From the light you can dream

of traces and beginnings

but humankind

is written nowhere here.

The best and most enjoyable poems in the anthology are those that lean into the personal lyric or shy away altogether. The wittily titled ‘Caving is not an optional activity’, by Estelle Price, recounts the utter panic of a school caving trip, during the minute when all torches are turned off to allow the eyes to accustom themselves to the absolute darkness of the underground.

It is not as if

I can’t hear water’s voice, a long way below my feet,

singing like my mother, suggesting a way out,

a journey through stone to light. It is only

that for the elongated minute we must sit

with head torches off, dark falls into my open mouth

begins to strip me from the inside.

Alternately, in ‘Linville Caverns, Humpback Mountain’, Carol Parris Krauss gives us something like a primordial myth, if our ancestors had been able to witness the glaciers advancing and receding on the scale of geological time. Channelling Ted Hughes, the poem remains strikingly original.

Mountain collapsed, a bindle full of woes

and weary strapped to his back, affixed

by lichen and laurel. Mountain lamented

limestone tears, coursed underland

streams – only the blind trout to witness.

Deft use of social media has given Deep Time an international range that’s refreshing, and the variety on offer is delightful. The geological treasures of Europe and the Americas inspire many thoughtful and innovative works, but it’s still a pity not to see our local landscape more celebrated. In the final Anthropocene section, there’s little sense that the sensibilities of Welsh poets have added anything to poems on mining. National treasures also go unsung: Paviland cave on the Gower, once home to the oldest human skeleton in Europe; the copper mines at Great Orme Head, or the cave near Trefil where the Chartists hid their pikes. With submissions for volume two still open, however, there’s more than time for our Welsh poets to pull their finger out.

More information about Deep Time and submission details for volume two can be found on Black Bough Poetry.

Thomas Tyrrell is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.