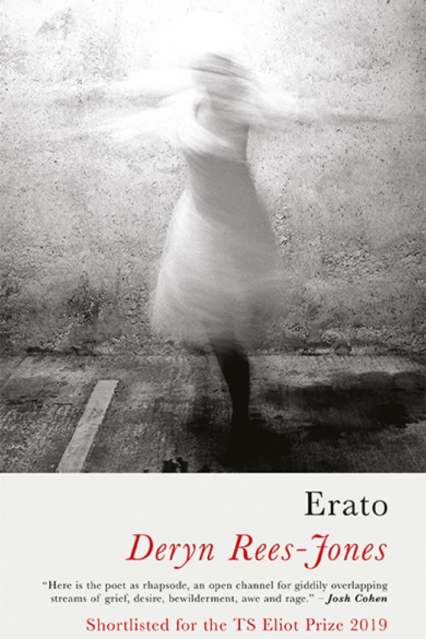

Thomas Tyrrell reviews Erato, Deryn Rees-Jones’ fifth collection of poetry which was shortlisted for the 2019 TS Eliot Prize.

The epigraphs to a poetry collection are a good place to judge its seriousness. I always have a fondness for those that mix high culture and low: Doctor Faustus and the Vengaboys, William Carlos Williams and Bruce Springsteen. Deryn Rees-Jones’ Erato poetry collection has three: Virgil, Elizabeth Bishop, and John Cage. Serious stuff, then. Ambitious. Not afraid to invoke the big beasts of the canon.

Then I turned the page of Erato and got the first surprise of the collection: prose. Not just prose, but autobiography — a slice of life, an email from the university appearing in Rees-Jones’s account. Prompting stray thoughts, more autobiographical nuggets, in separate, almost freestanding blocks of text, reminiscent of Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, though that book was presented as a novel.

Next in the Erato poem collection was a poem, recognisably a poem, the lines breaking before the page’s end. There’s a title, “Líthain and Cuirithir”, to google and find out about the forbidden love of two seventh-century Irish poets.

Excellent. Surer ground. Only the poem is struck through in its entirety. Still legible, but crossed out, discarded, and, paradoxically, collected.

In a later poem in Erato, in which the redactions are more thorough, almost untraceable unless you hold up the page at an angle to the light, Rees-Jones talks of “the impatience of the bad reader […] the reader in a hurry to be determined. decided upon deciding (in order to annul).”

At the risk of being that same bad reader, I resolve this poem in Erato as a deliberate farewell to an earlier style, abandoning the lyric uttered from behind the Yeatsian mask of figures from history or myth; the desertion of the circus animals. The poems of the rest of the Erato collection speak entirely in the lyric ‘I’ of the poet herself, which fits neatly with the title, Erato, the lyric muse, combined by wordplay with errata, another concern of the collection, with its strikethroughs and redactions.

A comfortable theory to hold for the next sixty pages of Erato, still alternating between prose and poetry. Many of the poems in Erato are full of loss. There are many In Memoriams, in titles and epigraphs. A father lost through a series of hospital poems, then a husband in a sonnet sequence that will feed any growing appetite for proper nouns, for the solidities of names and landscapes after these ghostly poems of unnamed universities and hospitals, authors and addressees.

Things broaden out thereafter in Erato. There’s an essay-poem, a neat hybrid that name-drops and summarises poets and critics like an essay does, but chases its theme like a poem. There’s the sudden beauty of a melody, striking through to the sadness at the Erato collection’s heart.

So many men

been passing through

but they’re not you.A bird on a wire

like a key in a lock

a moth on a stoneso much the stone

it could never leave.

They’re not you.One carried a canvas

instead of a flame,

one lied to his wifeand lied again.

One wept for his mother

and called me her name:they’re not you.

The poems in Erato never lose the intensity of personal speech, never take on another voice or mask, but they also touch on the sore points of our lives, the things we shy away from and hate to revisit. Paris in the year of Charlie Hedbo. Drone strikes. Jimmy Saville. Donald Trump clenching Theresa May’s hand on the White House steps. They remind me throughout of Colette’s advice to a young writer: “Look for a long time at what pleases you, and longer still at what pains you.”

They are worthy of a good long look.

Erato, the poetry collection, by Deryn Rees-Jones is available now from Seren.

Thomas Tyrrel is an avid contributor to Wales Arts Review.