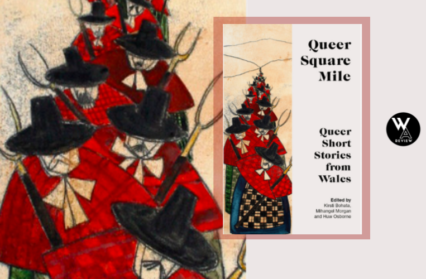

Joshua Jones reviews Queer Square Mile, a milestone volume of short stories shining a light on queer writing from Wales, spanning both centuries and genres.

The significance of Nonconformist religious movements in Wales cannot be overstated — where working-class communities developed their own networks and meeting houses, and led to the prosperity of many settlements and advances in education and legalisation — the movement was inherently conservative. Women were rendered invisible despite being the prominent percentage of chapelgoers in the congregation. Attitudes were strict towards alcohol, what literature was circulated — and, sex. To boldly represent sex and sexuality within literature was scandalous, so like many subversive English-language writers, Welsh writers of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries opted for coded, symbolic language to indirectly and subtly write about queerness; as otherness, sex, sexuality and same-sex romance.

A Welsh Labour MP (Leo Abse, Labour MP for Pontypool) was instrumental in the Sexual Offences Act in 1967, which legalised homosexuality in England and Wales. However, the law stated that same-sex must be consensual between two men 21 years old or above, and in private. Homosexuality was legal, if it’s behind closed doors. This only led to further vilification of homosexuality in the decades that followed, during the AIDS crisis, and Thatcher’s Section 28, but also dedicated political activism in the 1970s-2000s. From the first page of the introduction right up until the author biographies page, Queer Square Mile doesn’t just present a chronology of linear queer liberation, or a history lesson, but instead provides a queer canon of literature that celebrates lives lost, hidden, and forgotten.

Queer Square Mile’s forty-six short stories are arranged into five broad thematic terms, with plenty of crossover between them, with the first section, ‘Love, Loss and the Art of Failure’ carrying the most weight at fifteen stories. Most of the stories collected here could be described as being presented with “slow, priestlike tenderness and deliberation while the big shadows twitched behind them” (The Kiss, Glyn Jones, 1936). The first story to open this section — and the entire anthology — is ‘The Treasure’ by Kate Roberts. Originally published in Welsh in 1972 this is a quiet tale of a woman, Jane Rhisiart, in her old age trying “to put the events of that life in their proper place”. She takes stock of the moments that have changed her most; her husband leaving her when she was thirty-five, to the realisation all her children had disappointed her through their selfishness, to the death of her “close friend”, Martha Huws. This story is quiet yet devastating, containing all thematic terms of this section and setting a precedent for the whole anthology.

Whether they’re depicting homoeroticised pit workers (possibly projected by the reviewer) in Glyn Jones’ ‘Knowledge’, the slow persistence of time in Kate Roberts’ ‘Christmas’, or the loneliness of denial and unvisited desire in many of these stories, such as ‘all the boys’ by Thomas Morris (a personal favourite of mine), these stories ache with longing and pain. And yet, loss and failure don’t have to be considered as straightforwardly negative experiences. As quoted in the Introduction, Judith Halberstram said “failing is something that queers do and have always done exceptionally well.”

Heteronormative, cisgendered society has and continues to be hostile towards queer love, longing and queer existences. Even now, there is still a long way to go in reaching queer liberation. And yet, failing to “succeed” in heteronormative time and space itself can be considered a success, demonstrated by stories such as ‘Go Play with Cucumbers’ by Crystal Jeans. At first, it’s a difficult read; initially it seemed that main character Polly punished Lou for being possibly drugged and sexually abused by Kimmy, but it’s also suggested that Lou is lying to cover up her cheating on Polly. Regardless, both characters are unreliable, untrusting and untrustworthy, but when the tension reaches its peak, they both burst into laughter at the absurdity of the situation. It completely dissipates the tension between them. Laughing in the face of success; which, to them, might look something like a traditional heteronormative, and boring, relationship.

While homosexuality between men was illegal, sexuality and romance between women was often overlooked or hidden. This is suggested in Rhys Davies’ ‘The Doctor’s Wife’ (1930). The story is found in the ‘Disorderly Women’ section, and is one of the five stories authored by Rhys Davies featured in the anthology. The protagonist, Phoebe, is surrounded by artists and actors (“effeminate” men, “nancy-boys”), and conducts an affair of sorts with Agnes. Her husband, the Doctor Morgan (self-described as an “A1 man”) suspects of her infidelity, and even catches Phoebe and Agnes kissing. However, he still believes she has been twisted by the company she keeps, and is actually having an affair with the “nancy-boy” actor, Emlyn Walters. The story is brilliantly humorous and positions Dr Morgan, the most respected, powerful man in the Valley, as someone quite clueless. This completely flips the power dynamic in a way that is satisfying to observe as a reader: the queer wife running away to pursue a life with another woman, while the man is left humiliated and overcompensating.

Throughout the stories written by Davies in this anthology, positions of power and control are explored, surrounding otherness or queer dynamics. There is the possessiveness of Policewoman Ella Dobson in ‘The Romantic Policewoman’ (1931), who oversteps boundaries and her responsibilities as an upholder of the law, to “protect” this “fallen girl”, Kathleen. Also the reclamation of power in ‘The Nightgown’, whose unnamed, downtrodden protagonist, after a lifetime of service to her mineworking husband and sons, is worked to death. As a final act of defiance, she is buried in the nightgown that she bought with savings she kept secret from her family. Because of the demands of the men in her life, she couldn’t wear nice dresses or be beautiful, but she chose to look beautiful and dignified in death. This is one of many quietly devastating moments in Queer Square Mile, and is an example of how Rhys Davies is revered as a master of the short story form.

A few more stories worth mentioning here; ‘The Man and The Rat’ by Pennar Davies (1941) effectively positions the perspective of the rat next to the scientist’s desperate pleas to a lover. The rat, written with great self-awareness, is frustrated that he does all the work while the lazy, stupid rats benefit from his hard work — “the one who does all the work does not get the profit” — while the man believes stupidity and “poverty of the mind” take advantage of other’s intelligence. It’s as much an exploration of class struggle and capitalism as it is a longing for the company of a lover, to be “others” together against “the normality of society”. The following quote is one of the most haunting moments in the anthology:

When I was your love, I had a sort of society of my own, and it was possible for me to challenge the normal word and its nasty enmity. But now […] I stand alone against the world, and the world is stronger than me.

And secondly; ‘Love Alone, Remains’ by Mihangel Morgan, who has two stories featured here as well as translator credits, appears to be non-fiction rather than short story. It collects fictional letters sent to an unnamed recipient, from a young, gay student from Austria, whom the recipient met in Cardiff and developed a friendship. The letters ruminate on poetry and books such as Last Exit to Brooklyn, exploring hedonistic homosexuality in clubs and pornography in Berlin, and queer longing for community. The letters are incredibly touching, while the ending, the unnamed recipient’s editorial note, is one of the saddest things I’ve read all year.

Writing about Wales, Welsh literature and culture is facing a resurgence of interest. Publications such as Just So You Know (Parthian, 2020), The Welsh Way (Parthian, 2021), Welsh (Plural) (Repeater Books, 2022), among others, are investigating the future of Wales through radical politics, gender and sexuality, Welsh culture and experiences. Parthian is one publisher leading the charge, publishing radical works such as Queer Square Mile that celebrate Welsh literature of the past and the now, while looking towards the future.

Queer Square Mile successfully anthologises a queer Welsh canon. The anthology does not insist on a chronology of progressive attitudes, nor does it assert contemporary identities or terms on the sexuality of the authors featured. This would be a fruitless quest, as there is no such thing as a linear path of progression, and it would be impossible to impress an identity onto an author. The stories here all feed into a collective Welsh melancholia, of lives inhibited but not lived to their full extent; of unvisited desires, of regret and “failure”. Like all good stories, the ones collected here reflect contemporary (queer) experiences; people living everyday lives, with all the nuances of love, sadness, catharsis, and complications that entails.

Queer Square Mile edited by Kirsti Bohata, Mihangel Morgan and Huw Osborne is available via Parthian.