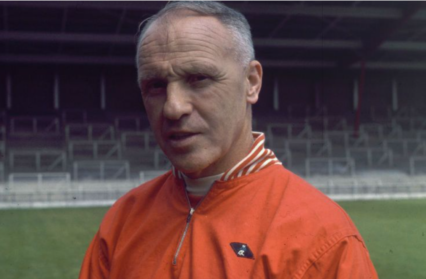

In a unique work of historical fiction, David Peace paints a picture of iconic Liverpool Football Club manager Bill Shankly in Red or Dead.

In May 1971 when Bill Shankly addressed the 100,000-plus cheering supporters of Liverpool Football Club from the plateau of the city’s iconic St George’s Hall – only a day after an FA Cup final that the club had lost – he spoke not just to the supporters who idolised him but also to the recently defeated players who flanked him: ‘Since I’ve come here to Liverpool and to Anfield I’ve drummed it into our players, time and again, that they’re privileged. To play for you! If they didn’t believe me then, they believe me now.’ In between the periods of sustained applause, the Scot continued in characteristically defiant terms. ‘Ladies and gentlemen, yesterday at Wembley we may have lost the Cup, but you the people have won everything. You have won over the policemen in London. You won over the London public, and it’s questionable if Chairman Mao of China could have arranged such a show of strength as you have shown yesterday and today.’

In David Peace’s latest book Red or Dead, a weighty and authoritative tome borne of meticulous research, the author seeks to explore the values and principles that Bill Shankly used to inspire such unprecedented levels of success and devotion, how he swiftly achieved messianic status in his adopted city of Liverpool, and how a man felt by many to be one of football’s ‘immortals’ struggled to come to terms with the shattering personal impact and resultant isolation of his wholly unforeseen relinquishing of the managerial reins. In doing so he draws out the contradiction of the defiantly jaw-thrusting orator and the sweetly devoted husband, the ruthless competitor and the man cast adrift. A story of one man and his life’s work, and of the man after that work. A story ruptured and segmented by a single jarring schism. A book of two halves. A man in two halves.

Though nominally a work of fiction, Red or Dead bears a weight of historical and personal accuracy that is testament to both the meticulous nature of the author and the breadth and accuracy of his source material. Unlike David Peace’s most famous work The Damned United, a book that has with time and a cinematic adaptation acquired a reputation for being a football book that even people who don’t like football can appreciate, it is hard to argue that Red or Dead will attract an audience much beyond those not already appropriately engrained in the rituals, customs and obsessions of the sport. Peace’s style, though uniquely compelling to this writer, is deliberately and compulsively repetitive in its nature, an unrelenting torrent of fixtures, dates, scorers and results, an intentionally knowing and evident reflection of Bill Shankly’s own fanatical and obsessive nature. Throughout, Liverpool (the team) is referred to only ever as ‘Liverpool Football Club’ as is still the wont of many of its fans, to distinguish it from Liverpool (the city) in much the same way as the inhabitants of the city itself will often seek to distinguish themselves from the rest of England, the rest of Britain, the rest of the bloody world. It is a spirit borne of defiance and contrariness that appealed to Shankly himself. One reflected within the book in the manager’s initial promotion of the city to his wife, Ness: ‘It’s a good city, love. More like a Scottish city. Good people, love. Like Scottish people. I can tell, love.’ And later in a valiant address to Celtic’s equally iconic Jock Stein: ‘You’ll see me (next) at Anfield, John. And Anfield is not in England. And Liverpool is not in England. Liverpool is in a different country, John. A different league.’

Given the timespan of the period that David Peace has sought to chronicle, it is inevitable that the subject of that earlier book, Brian Clough, makes a number of cameo appearances within Red or Dead in a series of minor exchanges that underlines the mutual respect that existed between the two. Between Shankly and Clough, between Shankly and Busby, between Shankly and Stein, working class men of socialist motivation and formidable disposition who built their parallel successes on the shared principles of hard work, honesty, and a disdain for personal aggrandisement. A team ethic, a five-year plan, a ten-year plan. A bloody revolution. It is this devotion to the principles of socialism and a hatred of any form of cheating that culminates in a hilarious episode in which Peace details Shankly’s explosive response to the concealment by a corrupt Romanian hotel manager of a case of Coca-Cola, smuggled through the Iron Curtain, especially for his players: ‘You are a cheat and you are a liar. Telling my boys, telling me, there was no Coca-Cola.When we had ordered Coca-Cola and we had paid for Coca-Cola. You are a disgrace to international socialism. You are a disgrace to your party. An absolute disgrace. And I am going to report you. Report you to the Kremlin, sir!’

But even more than the Scot’s socialism, it is his devotion to the fans of Liverpool Football Club, the fans even more than the club, the fans who are the club, whom much of Red or Dead is fixated upon – ‘I thank you boys for supporting Liverpool Football Club. Because we could do nothing without you. We would be nothing without you, boys.’ There are countless instances of interactions, personal and tender interactions, with the people who pay the wages of the players, the people – as is now – without whom the players would be nothing. A relationship that becomes even more acute with the passing of time and the socio-economic impact upon Merseyside of right-wing market economics that would succeed in decimating Liverpool’s economy and the self-respect of its labour force. In writing about a city which at one point only had the success of its football teams to cling onto, only football to represent civic and community pride, David Peace does not shy away from the prescient intimations of impending tragedy. Whether it be the private insight the author offers us into Shankly’s distress upon learning of the deaths incurred in the 1971 Ibrox disaster, or the Scot’s personal response to the media’s vilification of football supporters in general, the spectre of Hillsborough is never far from the surface of the narrative.

How Shankly would have reacted to the tragedy, the body blow it would have been to his fundamental belief in the basic requirement to treat others with decency and respect, a crime upon his people. Shankly’s people. Liverpool people. In a passage that follows a sequence of factual accounts of increasingly brutal instances of football violence that beset the country throughout much of the seventies, a post-retirement Bill Shankly confronts a journalist who recognises him amongst the throng of other Liverpool supporters leaving an FA Cup semi-final replay between Liverpool and Everton. In doing so, Peace uses Shankly as the mouthpiece for the downtrodden and the vilified, for the 96 human beings who would ultimately be killed on the cold hard concrete of the Leppings Lane terrace in the Hillsborough Stadium, Sheffield: ‘There was water dripping on me throughout the match. And there were little boys and little girls with only singlets on. They had spent all their money to get there. And they were soaked to their skins for their trouble. And then you people come out in the media and you say, these are the people we don’t want. They are hooligans. Hooligans. And we don’t want them here. And it appals me. The way you make them sit or stand in the rain in pens. The way you treat them like animals, worse than animals. Branding them as animals, branding them as hooligans. And hoping they will not come. Don’t you realise that without these people, without these boys and girls, there would be no game? Don’t you realise that throughout the country these are the people who will spend all their money and do without a pair of shoes to support their team? Don’t you bloody realise? Don’t you fucking care?’

The personal impact of Shankly’s eventual retirement, a decision taken by the man himself, one initially intended to allow himself the precious luxury of time with his beloved wife, Ness, is explored by the author in painfully forensic detail, a once-towering emperor swiftly diminished to the role of an impotently passive observer. A man trapped outside the gates of the citadel, the citadel he constructed through blood. His red, red blood, his sweat and his tears. And Liverpool, Liverpool Football Club, does not come out of this covered in glory, the glory that did not exist at Liverpool Football Club before Bill Shankly’s arrival at the ramshackle weed-strewn stadium that would eventually become his Vatican City, the glory of which he would always deserve. Peace details the former manager’s repetitive, fruitless wait for any kind of communication from the club that he led to untold success, for a token of its recognition, a letter, a ticket, an invite to an away game. A painful disconnection that is best exemplified by the Liverpool Football Club’s chairman openly discouraging Shankly to stay away from the club’s training ground for supposed fear of undermining Bob Paisley, the new manager. A shattering blow, an excommunication, or in Peace’s brutal language, ‘a cattle-gun to the head’.

For this writer there are two calculatingly understated yet nevertheless standout moments in David Peace’s work, two private and unassuming instances that typify the two sides of the man – Bill Shankly, the showman, and Bill Shankly, the humanitarian. The first, a pre-match portrait in the dressing room at Old Trafford, Manchester, a fleeting glimpse of the performer preparing to meet his audience: ‘In the dressing room, the away dressing room. Bill Shankly in his coat, Bill Shankly in his hat. In the mirror, the dressing-room mirror. Adjusting the lapels of his coat, adjusting the brim of his hat.In the mirror, the dressing-room mirror. Bill Shankly smiled.’ Here, the parallel that is drawn between Shankly and Sinatra (deliberately, or otherwise) is both vivid and utterly fitting; two men, both of a resolutely blue-collar background, who took on the world and did it their way, uncompromisingly so. The second, the perfect encapsulation of the difference between Shankly’s focus – the fans, always the fans – and that of the directors of Liverpool Football Club in 1959, the year that the manager took up post. When Bill Shankly complains about the state of the toilets at Anfield, the directors are at first baffled, amused even, before eventually realising that it is the condition of the facilities available to the fans that are deemed to be unacceptable: ‘The ones in the stands. The ones the people who pay to watch Liverpool Football Club have to use. Those people who pay my wages. Those people, their toilets’.

It is a powerful passage, a sobering passage, a depressing passage, because as much as this formidable book is an ode to what was won, won by Bill Shankly, won by Liverpool Football Club, it is equally as much about what we, our society, in its ugly impetuous rush for short-term personal acquisition at the expense of human decency, has lost. What we have lost.

Craig Austin is a Wales Arts Review senior editor.