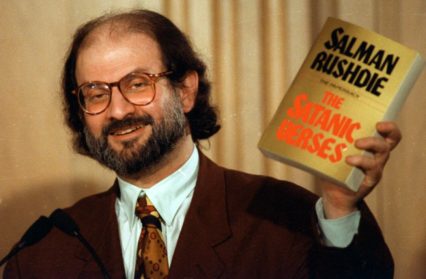

Following the shocking attack on the writer Salman Rushdie at an event in New York last week, the journalist and broadcaster Adrian Masters – a lifelong admirer of Rushdie – gives a personal view of the work that means so much to him.

As I write this, in my peripheral vision, is a shelf of books on the top of a bookcase, level with my shoulder. The shelf is full of books by Salman Rushdie, the result of three decades of reading and enjoying his work. I read recently how, frustrated that the Satanic Verses furore continues to overshadow the rest of his work, Rushdie quoted his friend Martin Amis about leaving behind “a shelf of books – to be able to say ‘From here to here is me.’” “Hopefully at some point,” Rushdie went on, “people will read all my shelf of books just as books rather than some kind of hot potato.” I hope, then, that he would be pleased to see the shelf at my shoulder, filled not with hot potatoes but big, expansive books which bring me such enjoyment and provoke so much thought.

There’s the most-recently-published, Quichotte with its deluded hero on a modern picaresque journey across the US, who wins us over to his delusions even as he confronts them. Next to him is the joyous Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Days in which the suddenly-levitating Mr Geronimo is said to have “taken leave of solid ground and moved upwards into, let us say, more speculative territory.” There are the injured icons of Vina Apsara and Ormus Cama, rock superstars in The Ground Beneath Her Feet which drops a mythic love story filled with operatically grand gestures into an eddy of other stories and a universe that is unspooling.

Probably my favourite, The Moor’s Last Sigh, is a sprawling story ostensibly about the family of the narrator, Moraes Zogoiby whose nickname echoes the painting referred to in the title. Enjoyably shifting, the narrative unpeels different versions of the same stories which change even as they are repeated. One pivotal episode is told three times in the same chapter. The central character Aurora Zogoiby provocatively visits the site of a naval strike and narrowly escapes violence. You have three different explanations as to how she escaped. All are possible.

Aurora is one of the great Rushdie characters: monstrous in many ways, deluded in others but bursting with charisma and vividly-mangled words. There are a lot of cover-ups in this book, both in the unlikely crime-plot and the repeated references to the notion of ‘palimpsest’.

There are the missteps on this shelf too, such as his saddest book, Fury; all misplaced pop-cultural references and brand names. Saddest because it feels like the pressure of being the public Salman Rushdie has undermined his efforts. You’ll find similar problems in The Golden House, but this time because the clunky Trump satire drowns out the Salman magic.

Serious subjects don’t always diminish the magic. For all its topic of terrorism, Shalimar the Clown delivers its lessons with a light touch and that Rushdie way with words and ideas: “He slipped across the globe like a shadow, his presence detectable only by its influence on the actions of others.” Then there are the essays ranging across subjects far and wide in three volumes, (one of which includes a letter explaining how the particular book that I now own used to belong to his early publisher and lifetime friend, the late Liz Calder). Also on the shelf is his massive, brutally honest autobiography, Joseph Anton, with its eye-opening accounts of the racism he endured in an English public school and the horrifying reality of living under constant protection and deadly serious death threats.

So yes, there is plenty of darkness and plenty to chew on in the books on my shelf. But it’s laughter that I think of when I think of Salman Rushdie: extravagant hilarity and rich writing. It was laughter that first drew me to his books in the 1980s when a fellow student read to me laugh-out-loud passages from Midnight’s Children, then his most-recently published novel. At their best, Rushdie’s books are packed with jokes and puns, some of them groan-worthy, but more often than not they’ll keep a broad smile on your face even while your brain is processing some profound ideas. That was certainly my view of him, when, a couple of years after first reading Midnight’s Children, I lay in bed listening to the same writer, dazed and scared, unable to answer fully the Today programme’s questions about what the fatwa meant for him and his life. Like everyone else, he’d just heard the news. Unlike everyone else, he couldn’t turn over and go back to sleep.

I don’t want to ignore the terrible attack on him in New York State last week or belittle the importance of his experience of having to spend so many years in hiding. But I do want to take him at his word and tell you what I’ve gained from enjoying my shelf of his books. It’s a shelf of stories: important and trivial, sad and sublime, ridiculous and sober, sometimes unfinished, sometimes failing as works of art, more often rich and satisfying, the stories of an extravagantly hilarious mangler and magician of words who’s also a profound and preposterous thinker. As well as the tumble of stories, you’ll find ideas, jokes, allegories and references to books, films, politics, music, art, comic books and full of sometimes contradictory opinion but all driven by an expansive, generous openness.

But if fun isn’t enough for you, what about the fact that each of the books presents and argues for a generous, open, large approach to life? In Midnight’s Children the narrator Saleem Sinai says that “To understand just one life, you have to swallow the world.”

Who or what am I? My answer: I am the sum total of everything that went before me, of all I have been seen done, of everything done-to-me. I am everyone everything whose being-in-the-world affected was affected by mine. I am anything that happens after I’ve gone which would not have happened if I had not come. Nor am I particularly exceptional in this matter; each ‘I’ every one of the now six-hundred-million-plus-of us contains multitudes. I repeat for the last time: to understand me, you’ll have to swallow a world.

It’s a book-long expansion of the Walt Whitman phrase, but it also serves as a motto for all of Rushdie’s work. His stories are in the tradition of ‘wonder tales’ from the Arabian Nights to modern sci-fi, stories that feature the fantastic but are not fantasy. Realism in literature, he notes, in an essay in Languages of Truth, can be escapist in that it tells you nothing about life that you didn’t already know. Whereas to the writer of ‘wonder tales,’ the marvellous strangeness of the world can be better conveyed.

“I like to argue,” he writes, “that reality isn’t realistic, and so I prefer the other kind of literature, what one might call the Protean tradition, which is more realistic than realism because it corresponds to the unrealism of the world.”

He quotes Randall Jarrell who said that “a novel is a prose narrative of some length that has something wrong with it”. Rushdie expands on that thought:

So: if a novel, or indeed a play, is bound to have ‘something wrong with it,’ then let it at least be a wonderful wrongness, speaking of the strangeness of the world’s beauty, a wrongness that seeks to wipe from our eyes and cleanse from our ears the dull patina and muffling wax of the everyday, which makes us see reality as monochromatic and hear it as monotonous, and to reveal the rainbow music of how things really are.

Long may he continue to reveal the rainbow music.