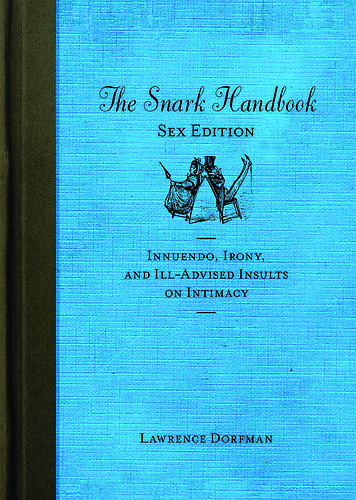

New York: Skyhorse Publishing

What is snark, exactly? No, not Lewis Carroll’s famous creation. Nor an aircraft.

Snark, as in sarcasm. Except not quite.

Actually, it might be easier to explain what it means to be snarky: a snarky comment is critical and cutting, an insult, although ideally an insult offered in a witty way. If you are being snarky, you want to be rude but also to be recognised for your cleverness. You need to be able to come up with the perfect pithy retort immediately, rather than later on, as in l’esprit de l’escalier (a.k.a. staircase wit, where you think of the greatest rejoinder when it’s too late and you’re already on your way up the stairs). Forewit, not afterwit, although clearly it’s a more straightforward matter if you’re writing rather than if you are speaking; book reviews are a common place to see snarky comments. Still, in short, it’s not so simple to be snarky, because it requires just the right mix of biting words, fast thinking, and sly wit.

One imagines Oscar Wilde being a master at snarkiness, and Shakespeare’s work certainly shows evidence of it as well, but in many respects, snarkiness seems to perfectly suit our modern era. It also seems peculiarly American – despite the American reputation for friendliness and the British reputation for acerbic humour – which is perhaps why it is being celebrated in recent publications from the US. It may be that America has looked to Britain for so long that writers and speakers there have been inspired to bring rudeness to new levels.

Lawrence Dorfman’s new series of Snark Handbooks, such as the clichés edition, the insult edition, the sex edition, or the parenting edition, explores snark in all its permutations. He focuses mainly on contemporary times but sneaks in some quotes and references to earlier ones as well. In the parenting book, for example, Dorfman quotes Mark Twain as saying: ‘When I was a boy of fourteen, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be twenty-one, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.’ And also: ‘Familiarity breeds contempt—and children.’ George Bernard Shaw is quoted too: ‘If you must hold yourself up to your children as an object lesson, hold yourself up as a warning and not an example.’

In the clichés book, Dorfman offers snarky responses to commonly used expressions. ‘How do I love thee?’ asks the famous poem. Dorfman: ‘I could count the ways but I think I’ll just refer to pages 17, 23, 102, and 103 of the Kama Sutra.’ Cliché: ‘A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.’ Dorfman: ‘But a bush in the hand is typically anywhere from $50 to $100.’ Cliché: ‘The pen is mightier than the sword.’ Dorfman: ‘Not sure who you’ve been fighting with but I’m not going up against a swordsman with a PaperMate—not now, not ever.’ Cliché: ‘It’s harder for a rich man to go to heaven than for a camel to go through the eye of a needle.’ Dorfman: ‘The only teaching from the Bible that’s completely ignored by Republicans.’

Meow.

Or, rather, snark.

Dorman’s snark books seem intended more as humorous texts to dip in and out of rather than in-depth analyses of what snark is and why it so popular just now. The latter would be interesting, but it’s only referenced in the short introductions to each section. Besides the quotes and retorts, Dorfman includes funny lists (the worst parenting books, including The No-Cry Sleep Solution by Jack Daniels) and quizzes (such as matching quotes to the films they come from). Some of the various quotes may inspire you to be more witty yourself, while others are so harsh they may make you glad that your humour is staircase.

‘Life is like a box of chocolates; you never know what you’re going to get’, to which Dorfman replies, ‘But, guaranteed, there’s a toothache involved.’ The snark books are like a box of chocolates too: good to try out, but sometimes offering toothache (or, rather, headache) instead of joy.