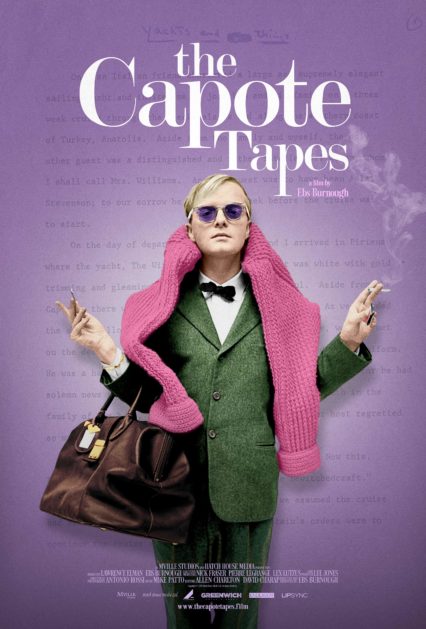

He was the celebrated literary lion embraced by America’s high society, who sparked his own downfall with a stinging, thinly veiled tell-all about his rich and powerful friends. The drunken, drug-addled and painfully public decline of his final years is still the most commonly conjured image of one of twentieth-century America’s most groundbreaking writers. Now, a new documentary re-examines the remarkable life of Truman Capote and delves into the literary mystery he left behind — just what happened to his final manuscript, Answered Prayers? Cerith Mathias speaks with the film’s director, Ebs Burnough.

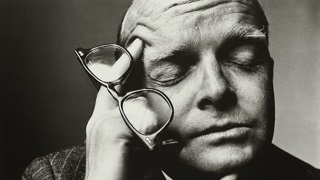

You may think you already know all there is to know about Truman Capote, at one time America’s most famous writer. The boy-genius from the rural Deep South who wowed the literary scene with his debut novel, Other Voices, Other Rooms when he was just 23; the author of Breakfast At Tiffany’s who went on to become the self-titled father of the non-fiction novel with the publication of In Cold Blood, researched with childhood friend Harper Lee, its success celebrated with a grand, generation-defining ball at New York’s Plaza Hotel. The mean-spirited gossip and gleeful participant in public spats that were lapped up by the press and an emerging chat-show scene, a stage on which he played out his final years often in a haze of alcohol or drugs having been banished from the kingdom of New York’s elite for publishing their deepest, darkest secrets in barely disguised works of fiction that were to supposedly form his never fully published Proustian masterpiece, Answered Prayers.

All present and correct? Not quite, says Ebs Burnough, whose new documentary, The Capote Tapes, offers a thorough insight into the life and work of the author through those who knew him best. ‘I thought there was a larger story to be told,’ says Burnough, ‘that said, I didn’t know where I was going to end up.’ A lifelong fan of Capote’s literature, first-time filmmaker Ebs Burnough (a former Whitehouse deputy social secretary and senior adviser to Michelle Obama), speaks to me over Zoom from the US.

‘We’d had these two feature films — two great portrayals,’ Burnough says, referring to 2005’s Capote, with Phillip Seymour Hoffman in the titular role, and 2006’s Infamous, with Toby Jones stepping into the writer’s shoes. ‘Both were very fixated on a slice of life, about the writing of In Cold Blood. They weren’t expansive, not what I would deem a biopic.’

His interest in Capote was rekindled after reading a biography of CBS mogul William S. Paley, where details of the friendship (and high-profile falling out) of the ‘supporting players’ — Paley’s wife Babe, and Capote, whom she called ‘True Heart,’ captured his imagination. ‘I had some connections to that world,’ Burnough says, ‘I knew a daughter of Babe Paley in New York.’

So began his project, which would take four years of research, interview gathering and production to complete. The documentary interweaves beautiful archive footage of 1950s and 60s New York, with Capote’s many TV appearances and candid footage of the author at play — entertaining at book launches, mixing drinks at a party, along with new interviews with friends and cultural commentators, among them the author Colm Tóbín, playwright Dotson Radar and US Vouge’s Editor at Large André Leon Talley.

The ‘secret sauce’ though, as Burnough calls it, comes in the form of previously unheard audio recordings with Capote’s nearest and not-so-dearest, made by George Plimpton, the late Editor of The Paris Review, for his 1997 oral biography Truman Capote: In Which Various Friends, Enemies, Acquaintances and Detractors Recall His Turbulent Career.

Burnough says he was already ‘well down the road’ of working on the film, when a friend suggested he contact George Plimpton’s widow Sarah about the cassette recordings which feature the likes of Lauren Bacall, Norman Mailer and Capote’s long-term partner Jack Dunphy. ‘I remember the moment,’ Burnough says of collecting the tapes. ‘It was a real discovery: hearing George’s voice, and then hearing the relationship he had with some of the interviewees, the ease they had together. You would hear him and Lauren Bacall and then you would hear glasses clinking, and you’d hear her say, “Oh darling, fix me another drink.” To hear them in their own voices is really something very special.’

The mixing of Plimpton’s archive interviews along with freshly gathered material offers up a fuller picture of Capote, one that doesn’t ignore, but that goes beyond the familiar ‘candied tarantula’ and ‘tiny terror’ caricatures, presenting alongside them a softer, more vulnerable version of author. For his part, Burnough says he began the project feeling ‘relatively agnostic’ about Capote as a person. His production team, on the other hand, was a different matter. ‘My production team hated him from the get-go,’ Burnough says. ‘They’d say, “How could he do this to his friends? What a tiny terror!” By the end of the process, they were all madly in love with Truman.’

Burnough says he didn’t initially set out to right any perceived wrongs where Capote was concerned. ‘I didn’t like him, I didn’t dislike him, I found him to be fascinating. I wanted to know more,’ he says. ‘I didn’t want to soften him, because if he were a person that just had sharp edges, then so be it.’

For Burnough, the key to unlocking Capote came in the form of a freshly recorded interview with Kate Harrington, Capote’s unofficially ‘adopted’ daughter. ‘It’s the heart and soul of the film to me,’ he says. Kate met Capote when he and her father became lovers and set up home together. Though his turbulent relationship with the hard-drinking John O’Shea wasn’t to last, Capote and Kate’s blossomed, and would last until the end of the author’s life. She went to live with him in his apartment in Manhattan’s UN Plaza, and he helped find her work as a model, taking her to Richard Avedon’s studio and then introducing her to his jet-set pals.

‘Kate is the one for me who gave Truman a soul,’ Burnough says. ‘You can be caustic and sharp and mean and all of these things, but for someone to consider you their father and for that person to be as warm and kind and intelligent and deep, then you had love and empathy and soul that you poured into that. Once I saw it, once I realised it, I knew it had to be an important part of the film, because it was another angle of him that we hadn’t been privy to see.’

The film opens with Kate Harrington talking fondly of her years with Capote, of the way her life changed: ‘he opened up the worlds of art, literature, fashion and meeting all sorts of accomplished people.’

Harrington says that she once complained of being bored at the gossipy society lunches she accompanied him to. Capote put her to work. ‘He told me that what I should do is sit and listen to the conversation next to us,’ she says in the film. ‘And on the way home, I could tell him everything they talked about.’ A habit she admits she has kept to this day.

Harrington also talks with authority about Capote’s upbringing in rural Alabama, where he had been abandoned by his social-climbing mother Lille Mae, who left him in the care of her ageing relatives in Monroeville. Years later, now re-invented as Nina Capote and living in New York (a trajectory not dissimilar to Holly Golightly, Capote’s famous heroine of Breakfast at Tiffany’s), his mother sent for him to go and live with her and her new husband. Once there, he didn’t find the family life he craved, never feeling that his mother fully accepted him. Unable to afford the lavish lifestyle that she’d so desired and on the brink of bankruptcy, Nina Capote took her own life. ‘Truman always said that was the thing he drank over.’ Kate says softy to the camera.

Capote’s subsequent desire for a family of his own at a time when, as an openly gay man, society didn’t permit him to have one, makes Kate’s part in Truman’s life all the more meaningful for Burnough. ‘It was important to show very clearly the life we lead today — the things we take for granted as just life. It was important to show Truman as the pioneer that he was because I think in LGBTQ history he has largely been lost as a mean queen or a bitter, bitchy person,’ says Burnough. ‘The reality of the situation is that he lived out loud, he lived his life as the person that he was and that’s really quite extraordinary for someone in that era to take it on the chin for all of us who follow.’ The documentary depicts in all its ugliness the discrimination Capote met with during his lifetime; allowing the viewer see it or hear it first hand certainly packs the punch Burnough intended.

Audio archive of Norman Mailer includes a description of an afternoon spent drinking with Capote in one of Manhattan’s Irish bars. Capote, Mailer says, walked in ‘looking like a beautiful little faggot prince.’ ‘I remember someone on the production team asking if we should keep that in,’ Burnough says animatedly. ‘Of course we have to keep that in, because I’m a believer that the only way that we grow and learn is by remembering. There’s something so powerful about the simple words ‘never forget’. We have to move on and we have to evolve and progress, but if we don’t remember the struggle, then we are damned to probably repeat it.’

A pioneer indeed, Capote carved his life experiences into the wider American experience. Undeterred, he took up his space in a society that was largely unwilling to grant him the right to do so. ‘Every gay life in those years took courage,’ Colm Tóbín says in the documentary. ‘I think it nourished him as a writer. It wasn’t as if he was seeing himself on television or in the movies or in any other way.’

Capote was a master of self-invention. A razor-sharp publicist, who choreographed his public persona meticulously, he appears chameleon-like through his writing, which is examined chronologically in the film. From the sensitive, elfin Southerner to the chronicler of 1950s New York, to creative journalist, to socialite and eventually, author of his own downfall, it is difficult to decipher who exactly the real Capote was.

‘I think the real Truman was a brilliant, terrified, lonely little boy that had been abandoned,’ Burnough says. ‘I think everything else was layered on top, the self-made dimensions that made him stronger and tougher and able to handle the world head-on given his size and his demeanour and who he was. I think it’s an incredibly powerful story. It’s the stuff of legend, the truth of self invention — the ability to take yourself out of a situation.’

Does Burnough ever think Capote found the happiness he was looking for? ‘I don’t think so,’ he says. ‘I think he had it, but I don’t think that he ever found it. You know, Kate has a daughter and her name is Truman. And you think — what a testament to who he was, that’s how she chose to honour him. You wonder what he would have made of that.’

A significant portion of the film deals with the years before Capote’s death, and the scandal of Answered Prayers, his infamous unfinished novel, parts of which were published in Esquire magazine in 1975 with devastating effects. The novel, which Capote had been working on for two decades and talking about publicly for just as long was going to be his masterpiece, lifting the lid on New York’s glittering café society, in the vein of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, written about the French aristocracy. One extract in particular – La Côte Basque, 1965 set New York’s gossip columns alight with its re-telling, using the thinnest application of fiction, the most personal secrets of Babe Paley, Princess Lee Radziwill, Slim Keith, Marella Agnelli and Gloria Guinness, a diamond-encrusted flock known as Capote’s Swans. The women, once his greatest conspirators and confidants, cried betrayal (loudly) and never spoke to him again, cutting him off entirely. Capote was devastated. ‘I’m a writer,’ he reportedly said, ‘what did they expect?’

‘Truman throughout his life always wrote what he saw,’ Burnough says. ‘At that time in his life he was heavily addicted to prescription drugs and cocaine and addicted to alcohol. So the writing, while it’s still very good writing to me, it’s not as strong as the writing from before and I think as such the nuance that he might have woven into the storylines was lost.’

Perhaps had Capote’s ‘artistic powers been where readers were accustomed to them being,’ Burnough suggests, the fall-out wouldn’t have been quite so devastating. After all, following the publication of Breakfast At Tiffany’s in 1958, several of New York’s ladies-who-lunch claimed the novella’s leading lady was based on them. ‘When we look at Holly Golightly and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, the idea when you read it that any person would want to hold their hand up and say, “Oh it’s based on me!” is insane. But the writing was so beautiful, it’s so lyrical, it’s so perfect that everyone overlooked the fact that she was a prostitute.

‘Had it been better, and it’s hard to define what better would be, but I do believe had he been in full possession of his faculties the writing would have been stronger and he would have come closer to achieving his Proustian wish.’

Despite telling many people that the Answered Prayers was finished, indeed many of the documentary’s contributors claim he’d completed work on the novel, following his death in 1984 (he was a month shy of his 60th birthday), no manuscript has ever been found. Will we witness another publishing sensation like that of his old childhood pal Harper Lee’s Go Set A Watchman I wonder, or is the likelihood that a finished manuscript was another of Capote’s tall tales?

‘I believe that it was written. I also believe that there’s a high likelihood that he may have, in a drug and drink-fuelled rage, done something silly, and thrown a chunk of it into the fire,’ Burnough says. ‘But I also think he was such a cheeky guy, there really is a possibility that he got the rest and he said,“Well, you know what? I’m just going to lock this away and they’ll be ready for it eventually.” That’s my wish, because I would love to stumble upon the rest of it and actually get a chance to see where he was going, how he was going to weave in all of those different storylines and create something really interesting.’

Something that Burnough is certain of, however, is that Capote would be delighted that both he and the book were still being discussed all these years later. ‘I always say, I wish he were here now, because I think he would be an incredible force on social media,’ Burnough laughs. ‘Truman would have been giving Kim Kardashian a run for her money. He would have been tweeting back, “Hey Kim, we don’t care!” He would have been tweeting back to Trump. He would have had all of us on our toes, somewhere between being horrified at what he said and loving it and laughing. The digital platforms that we have today would have really been his sweet spot.’

Truman Capote’s attitude to the truth was that it should never get in the way of a good story. ‘Is truth an illusion, or is illusion truth, or are they essentially the same thing?’ P.B. Jones, the narrator of Answered Prayers muses. ‘Myself, I don’t care what is written about me as long as it isn’t true.’

In 1986 the incomplete chapters of Answered Prayers were published with an introduction by Capote’s long-term literary editor Joseph Fox. ‘There is only one person who knows the truth,’ Fox writes, ‘and he is dead. God bless him.’

The real truth of who Capote was when the cameras had stopped rolling or the pencil lay idle on his favoured yellow writing pads will perhaps remain as elusive as his completed final novel. But Burnough’s incisive, considered film offers more than a momentary glimpse of the man behind the many masks.

The Capote Tapes is available now at Altitude and digital platforms across the UK and Ireland.

Cerith Mathias is a journalist, TV producer and freelance writer as well as Co-Director of Cardiff Book Festival and co-founder and trustee of Pontypridd Children’s Book Festival.

Header image: Ebs Burnough and Dick Cavett.