Tyler Keevil’s second novel, The Drive, is exactly what it presents itself as: a road-trip. It’s a rite-of-passage tale about a young guy who’s split up with his girlfriend and decides to get over his broken heart by going on an adventure.

So far so good.

The Drive is a perfectly confident, humorous and accomplished book. Written in the first person, Keevil’s protagonist Trevor has a strong West Coast vernacular that can be funny and ironic. He makes dry observations about American culture that makes the book an easy read and propels the plot along. Not that there is much of a plot, but then, this is a road-trip and that’s the nature of the beast. They’re episodic. Keevil’s aware of that and early on Trevor himself points out to the director of a road movie he’s helping to shoot that the story seems uninspired: ‘about one character’s journey. A personal odyssey. But with all these trippy and surreal elements thrown in.’ At that point, I had high hopes for The Drive. Okay, so this isn’t just going to be a twenty-first century re-hash of Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas.

Mouth-watering.

I tore through part one like Trevor speeding down the interstate in his Neon. The novel was proving to be kind of mindless though, and I started feeling a bit like I’d been huffing whippets with him, but on the upside it was totally digestible, and plus I started to talk like Trevor in my head, which was fairly amusing. Trevor, from his detached perspective, regards everything as ‘fairly’ something or other. ‘Fairly awkward’; ‘fairly creepy’; ‘fairly cinematic’. Fairly banal.

But there’s a darkness in him that suggests a descent into something deeper and more expansive than the surface weirdness that he keeps encountering on the road; the seemingly random dream-like struggles he has with various freaks and villains on the way. Eating nothing and ingesting a constant stream of whisky and mescal, Trevor is bound to stumble on some inner crisis of his own and the book will become meaningful.

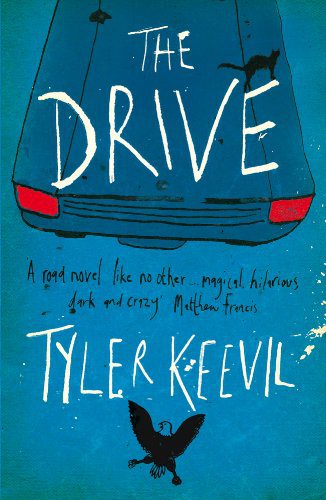

385 pages, Myriad Editions, £8.99

I began hoping something really profound would happen to Trevor, but for all the dramatic near-misses and scrapes with disaster, he never seems to gain much from his experience, other than perhaps glimpses of self-awareness that reveal his opinion of himself as a total jerk. These glimpses are funny and redeeming, and on a few occasions – when I’d almost written him off completely – I managed to climb back aboard the Neon, extending my loyalty in the same way as his faithful flea-ridden cat seems perpetually to do.

Undoubtedly there’s something of memoir in The Drive: Keevil graduating methodically through life from his first novel of teenage loves and losses to the journey of discovery of the twenty-something recovering from his first heartbreak. That’s good material and I’m right beside him all the way. But The Drive proves to be something of a missed opportunity. There is so much room for introspection, soul-searching, personal growth and enlightenment; the things that happen in reality could so easily inform Trevor’s inner landscape and an existentially great novel might have emerged. And yet the whole thing somehow never really seems to get beneath the skin. It remains, at worst, just a bit silly. If it’s a credible memoir-style novel, I want Kerouac’s intensity. I want his passion and his insights, whether it warms me to him or not. The beauty of On The Road, and Fear and Loathing for that matter, is that you’re not obliged to like the characters. That’s not what it’s about. It’s that they provoke a response. For better or worse. The writing, and the characters that populate the novels, burn. If The Drive is an attempt at a ‘failure’ novel in the true American tradition, then it is woefully lacking in the thoughtful introspection required to pass muster.

I realised about half way through that I might be happier if it simply presented itself as a sort of Bill Bryson-esque comic travel piece. I kept hoping that the naïve Trevor would journey through a surreal and mythical landscape and come out evolved. I kept looking for the odyssey to transcend the inane. Keevil can definitely write, and there’s some beautiful landscaping that puts the reader right in the thick of his sensually saturated jaunt. But the personal relationships lack depth. I never really cared about Zuzska, his Czech sweetheart until it was too late, and for all the accolade he heaps on her and his beloved Beatrice, they remain stiff two-dimensional portraits.

As a last resort, I tried to get myself swept away on the promise that this was actually magical realism. That the whole thing was a symbolic nod to Homer and that perhaps, having only read The Illiad, that some of the esoteric mystery was lost on me. It brought to mind The Magus, and whilst I’m aware that John Fowles’ brilliant novel is steeped in Greek literary references that I may or may not be aware of – that a thorough and comprehensive knowledge of the classics could only serve to enrich and enhance a reading of Fowles’ masterpiece – the genius of his writing is that it in no way detracts from its standing should the reader be anything less than on a total intellectual par with its author.