September 15th 2023 marks the 60th anniversary of the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. A shocking act of racism that killed four girls attending Sunday school. It was the deadliest moment of the US civil rights era, a tragedy that ushered in sweeping legislative changes that had been long called-for across the country.

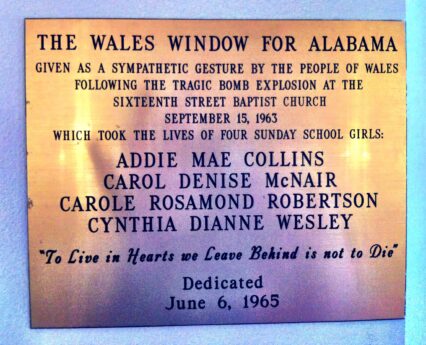

Events that day also began deep connections between Wales, the church and the movement for racial equality following a national gesture of goodwill and compassion in the form of a stained-glass window known as the Wales Window, created by the artist John Petts. It forever linked two families on opposite sides of the Atlantic — the Petts family in Wales and the family of the Reverend John Cross, the church’s Pastor in Alabama.

To grasp fully the significance of the change brought about by the actions of their fathers, Cerith Mathias spoke to the children of those changemakers John Cross and John Petts to ask about their memories of that time and what the Wales Window of Alabama means all these years later.

A version of this essay was originally published in Home to You: 10 Years of Wales Arts Review.

The morning of Sunday, September 15th 1963 began grey and overcast in Birmingham, Alabama. The days preceding it had been cloud-covered, filtering the city in a slate-toned light. The temperature a little below average for the area at that time of year, long sleeves replacing the bare arms of a scorching Southern summer a little earlier than usual.

For 13 year old Barbara Cross, despite the weather the morning dawned with a sense of excitement. It was the beginning of the school year, her second as a resident of Birmingham. Her family had relocated to the city in June of the previous year, when her father the Reverend John Cross had been called to Pastor the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, the oldest black church in the area. It was to be the first time he’d initiated Youth Sunday under his ministry, and she was eager to get to church and enjoy the proceedings with her friends.

Her mother had decided to stay at home that morning; she wasn’t feeling well and with Barbara and her three siblings, Michael, Alma and Lynn on the brink of another school year, she had chores keeping her busy, so father and children made the 20 minute journey across town from the Parsonage to the Church. Autumn was Reverend John Cross’ favourite time of year. A change of season, a punctuation point in the calendar often associated with new beginnings, a time to refocus.

That morning, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, a large, broad and solid looking structure that commands the corner of Sixteenth Street and Sixth Avenue North was filled with the chatter of children. After their Sunday school classes, which were held in the church’s basement, the younger members of the congregation were to take part in the main morning service upstairs. With classes underway, Reverend Cross began the final preparations for his sermon, taken from Luke 23:34, in which Jesus on the cross asks God to forgive those crucifying him. As always, there were church matters for him to tend to, including many administrative tasks. There’d been a problem with the gas hot water heater in the kitchen area – something that would need to be fixed. A job for another day however, today his attention was focused on his congregation, on the children of the church on Youth Sunday.

In the church basement, Sunday school lessons were beginning to wind down. Barbara Cross’ class had finished and fresh in her mind was that day’s lesson – ‘A Love that Forgives,’ where along with her classmates she’d learned about brotherly love and the act of forgiveness. Forgiveness was to be the overarching theme of worship that day, one that would be continued in Reverend Cross’ sermon.

Many of the children were milling around in the basement before heading upstairs for the morning service, one group of boys deep in conversation about football and the church band that they were all members of. Barbara Cross was still in the basement too, her teacher, Mrs DeMann had given her a task to finish before joining the service upstairs, she was to write down the names of those who would be moving up to the next age level in Sunday school. A good, respectful student, Barbara set about the task at hand, declining her friend Addie Mae Collins’ request that she join her and three classmates, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley and Denise McNair in the girls bathroom after class. Promising Addie that she’d be along as soon as the assignment was finished, Barbara handed over her wallet for safekeeping, telling her friend that she’d collect it from her in just a moment.

Upstairs, her father had left his study. John Cross made his way to the Sixteenth Street side of the building to sit in on the women’s bible study class, their lesson that morning also about forgiveness. The time was a little before 10.20am. As Reverend Cross listened to the women’s discussion, a telephone rang out in the church’s office. 15 year old Carolyn Maull, in her role as Sunday school secretary answered.

‘Three minutes’ said a male voice before hanging up.

Carolyn replaced the receiver and started to make her way out of the office. Downstairs, the boys’ animated conversation was still in full swing. Barbara Cross had just added a fifth name to her list of students. A great roar tore through the church, a noise unlike anything the children had ever heard before. At first, the Reverend Cross thought the faulty water tank in the kitchen had exploded, but soon realised the fumes filling the air weren’t gas, they were powder. The building shook violently and in the basement everything went dark.

When the bomb exploded it was 10.22am.

Hours earlier, under the cover of darkness a small splinter group of the racist white supremacist group the Ku Klux Klan, had carried out something they’d been overheard boasting about planning. The group, all local to Birmingham, had planted a stack of dynamite under the church steps and set a timer for the blast to coincide exactly with that Sunday’s worship.

On the other side of the Atlantic, in the small Welsh coastal village of Llansteffan the weather was brighter. A sunny September day greeted the artist John Petts as he prepared to spend his Sunday with the usual division of family and work, a split between kitchen conversations and hours spent in his studio, a converted cow-shed in the garden of the family home – Cambrian House in the heart of the village. A home life John Petts, the acclaimed stained glass artist shared with his wife, the poet Kusha Petts and their three children, David, Catrin and Michael.

Owing to the time difference, morning in Alabama was afternoon in Wales, and at the time the Cross family were settling in to church proceedings, John Petts was already stationed in his studio. After a typical Sunday morning of answering correspondence and dealing with paperwork, he’d left his wife Kusha sitting in the garden enjoying the September sunshine to continue work on a window he’d been crafting for three months. As he worked, his radio burbled in the background, tuned as it often was to the BBC’s Home Service.

Back in Birmingham, Reverend John Cross had quickly grasped the situation unfolding in his church. Calling on his congregation to evacuate the building, to ‘get out!’, he ran downstairs, criss-crossing the basement going from one room to another to make sure the children were leaving safely. When he finally reached the pavement outside, he stood in clouds of smoke, dust and debris; some of his congregation were injured, others frantically searched for family members and friends. His daughter Barbara had been struck in the head by a light fixture, her younger sister Lynn, aged just 4 had been taken to hospital. The church itself had been badly damaged, the sanctity of promised sanctuary wounded. The stone steps had been destroyed, windows smashed, the twisted fragments of brick and glass spilling out on to the street. The face of Jesus in the church’s main stained glass window was blown clean out, his watchful gaze seemingly vanished.

Needing to calm the amassing crowd, Reverend John Cross began pacing the pavement. ‘Please go home,’ he urged, tears streaming his cheeks. ‘The Lord is our shepherd, and we shall not want.’

People were still unaccounted for. Stepping back into the church through a gaping hole that had been slashed into the east wall, Reverend Cross and others began to dig through the debris. There, where only a short time before the girls bathroom had stood, they discovered four bodies. Under the wreckage lay 14 year olds Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley and 11 year old Denise McNair, huddled together, John Cross thought, as if they had been hugging.

In Wales, as the afternoon sunshine outside his Llansteffan garden studio was beginning to melt into early evening, John Petts’ attention had been abruptly snapped away from his work by a news bulletin on the radio. News of the atrocity unfolding in Birmingham had travelled. Horrified firstly by the loss of life – his daughter Catrin was the same age as three of the girls who had perished, as an artist details of the church’s smashed windows also caught his attention. ‘My word, what can we do about this,’ he thought, his mind not able to pass over the information he’d just heard. He hurried from his studio to tell his wife Kusha of the news, an idea already nagging at him that somehow they ought to do something in response, a ‘gesture of fellowship and goodwill… surely that’s better than just tut-tutting and protesting and saying “how dreadful,” and then passing on to a happier part of the news.’

The thought would give him no peace, sending him back and forth between studio and wife, wife and studio, the details of the racist bombing swirling around his mind. Kusha Petts, equally appalled by the news, yet knowing her husband’s nature issued him with the prompt he needed. “Now look,” she told him, “Either do something about it or shut up.”

It was the jolt Petts needed. Sunday though it was, he headed for the large black Bakelite telephone in the kitchen and dialled the number for his friend David Cole, the Editor of The Western Mail. Cole suggested running a fundraising campaign in the newspaper to replace the large stained glass window in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church with a window of Petts’ design. No one was to donate more than half a crown each, to ensure that the gesture would truly be given ‘as a gift from the people of Wales.’ Two days later on Tuesday September 17th, the Western Mail launched the campaign with the headline ‘Alabama: Chance for Wales to Show the Way.’ Within a month the fund’s target had been surpassed and Cole quickly found himself making preparations for John Petts to visit Alabama to discuss the replacement window with the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church’s pastor, the Reverend John Cross.

The campaign had been a success. One problem remained however. Constrained by the segregationist Jim Crow laws practiced statewide in Alabama, as a white man, John Petts’ presence in a black neighbourhood in Birmingham, working with a black church would not only be met with disapproval by the state’s devoutly pro-segregationist Governor, George Wallace, it would be mortally dangerous for both himself and Reverend John Cross also. Knowing this, both men decided to bridge the man made divide neither chose to recognise.

‘The people of Wales offer to recreate and erect a stained glass window to replace one shattered in the bombing of your church,’ read the telegram sent by David Cole and John Petts to the Reverend John Cross. ‘They do this as a gesture of comfort and support.’

The reply — Wales was ‘the only country to offer such direct and material assistance.’

In Birmingham, the months prior to September 15th 1963 had been tumultuous. One of the most racially divided cities in the US, a situation enforced both legally and culturally, racially motivated bombings were not extraordinary at that time. Nearly fifty unsolved incidents had taken place from the late 1940s through to the mid 1960s, leading to the city’s nickname ‘Bombingham.’ A hub for the fight for civil rights, the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church had become the beating heart of the movement’s campaign to be ‘free in ’63’, the streets directly outside it where Dr Martin Luther King Jr’s calls for non-violent protest were met with water cannons, baton wielding police officers and the snarling, snapping jaws of police dogs. The Reverend John Cross had agreed to Dr King’s request that the church be used as a meeting place for the civil rights movement and become the organising centre of the children’s crusade, a drive that produced the Birmingham Accord. On May 8th 1963, an agreement was reached which sanctioned amongst other things, the desegregation of schools, lunch counters, public bathrooms and drinking fountains within 90 days.

Dr King proclaimed that change was coming to the ‘the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States,’ and that ‘the walls of segregation will crumble in Birmingham and they will crumble soon.’

Just a fortnight before the Sixteenth Street bombing, on August 28th, King shared his dream at the Lincoln Memorial with over two-hundred-thousand people who had marched on Washington. A menacing tension crackled through Birmingham’s streets.

September 4th had seen the first three of the city’s schools integrated. White supremacist rhetoric spat back biliously at the move, and the ten days that followed were filled with violent anti-desegregation protests. Rioting ensued and the home of civil rights attorney Arthur Shores, who was campaigning for school integration was bombed for the second time in fifteen days. Suspected Klansmen toting confederate flags planted themselves at two of the newly desegregated schools’ gates. On September 10th, President John F. Kennedy federalised the Alabama National Guard to enforce integration, a deployment of federal authority not seen since reconstruction. Speaking to The New York Times, state Governor George Wallace stood firm in his prejudice telling a reporter that in order to halt integration, ‘What this country needs is a few first class funerals.’

A week later, a group of white supremacists enacted Wallace’s rhetoric by planting a bomb at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. The bomb would senselessly snuff out the lives of Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley and Denise McNair and injure twenty two others. The resulting chaotic unrest immediately afterwards also claiming the lives of two teenage boys, 16 year old Johnny Robinson who was shot in the back by police and 13 year old Virgil Ware, who was shot while riding through a residential suburb on the handlebars of his brother’s bike. The bombers, members of a splinter group of the Ku Klux Klan known as the Cahaba boys, were already suspected of other racist attacks in the city. Despite being identified in the investigation that followed the bombing, it would take another forty years before they were brought to justice. The Reverend John Cross and his daughter Barbara would testify at all three trials.

Events in Birmingham were condemned the world over. The death of the four girls shocking those with the power to bring about meaningful change to enact it. That Sunday altered forever the course of the civil rights movement, according to many, acting as a catalyst for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. A day never to be forgotten, commemorated by a stained glass window designed and made in a small Welsh village and installed to convey the brighter days that its creator hoped the southern sun would reflect through its panes.

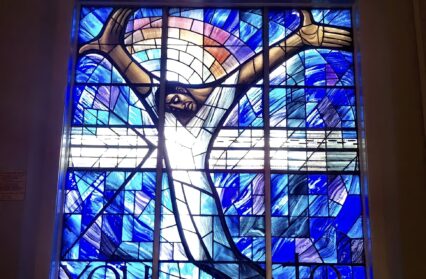

Indeed, Petts’ window would stand as more than a gesture of support. Its bold design became a symbol of the civil rights movement itself, a statement that change was not coming, but that it was already here. The window told those supporting the segregationist status quo that things were going to be different from now on in. Petts’ window would be the first ever depiction of a black Jesus in stained glass form in the United States.

John Petts sailed to America in March 1964, spending a week with Reverend Cross and the church’s building committee. His presence and the purpose of his visit kept from the press for fear any publicity would result in racist backlash. He was accompanied everywhere by a bodyguard, and the Reverend Cross sent his wife Julia along with Barbara and her siblings to stay with relatives for the duration of Petts’ time in Birmingham.

Petts and Cross had much in common. Reverend Cross was a people person who loved to talk, while it was said that John Petts had the gift of the gab. Both Johns had also served in the Second World War. Petts, a conscientious objector who abhorred violence of any kind, was reluctant to talk about much of his wartime experience which had placed him at one point near the Nazi concentration camp Bergen-Belsen. Cross had spent time in France and Japan and had suffered the humiliating racist abuse of his fellow American soldiers throughout his service. Both men were witness to the ugly the behaviour of human beings. The window, for both, was to convey another way. ‘What this window is fighting about,’ Petts said ‘is what man does to man.’

Upon Petts’ return home to Wales, the importance of the commission weighed heavily upon him, and the artist struggled to settle on a design, one that would speak to ‘the problem of what we do to each other during the short time we have the gift of living on the earth.’

Both Petts’ sons David Felix- Dexter and Michael Petts remember that time in their lives vividly. The level of activity in their family home increased significantly while their father worked on the window.

Michael, who was 7 in 1963 remembers ‘a level of angst’ in the house. ‘Both of my parents were, disturbed by this event. And I can remember a lot of to-ing and fro-ing going on and this heightened state of alarm and disturbance.’

David, who was 16 in 1963 recalls the significance his father immediately placed on the window.

‘This one had a completely different atmosphere and energy and momentum attached to it, the energy was quite remarkable,’ he says. ‘Our little coastal village in Wales was linked to a major international story. At that time, the death of children by violence was significantly other, it was a major piece of international news.’

David remembers clearly the moment Petts, after much struggling, struck upon the design for what would become known as the Wales Window.

‘He drew a hand, and such was the power in that drawing and the atmosphere and the energy of it, that he had to come up into the kitchen, into the house to tell us about it,’ David says ‘He wasn’t quite shaking, but he was in a form of shock because something had happened that took him right out of himself. The bar was raised in this drawing that he’d done.’

Inspired by a verse from Matthew 25:40 that presents the message of brotherly love: ‘Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me’, Petts’ window would depict a black Jesus ‘a suffering figure in a crucified gesture, with one hand flung wide in protest, the other in acceptance.’ Above his head, a rainbow constructed of tiny pieces of blue, purple and pink glass to represent racial unity. Underneath the crucified figure the words ‘You Do it to Me’ in large black lettering. Below that, spelled out on tiles of red glass, ‘Given by the People of Wales.’

David was to model for the torso of Jesus, asked by his father to twist and turn in different directions, the contortions representing the bodies of civil rights protestors under attack by the painful jets of police water cannons.

‘If you look at the window,’ David says ‘the figure is tilted to the left. So I had to stretch in that position so John could look at what was happening with my breast bone and muscles.’

The head of the figure was modelled for by a photographer friend of John Petts, a man named Bill Paterson, who travelled to Llansteffan from London to stay with the family. The artist was also to take inspiration from his visits to Tiger Bay’s multi-racial Rainbow Club, where he sketched the movement of the children at play.

Both sons are in agreement however that the most vital figure in Petts’ process at that time was their mother, his wife Kusha.

‘Without my mum, it wouldn’t have happened.’ Michael says. ‘She gave him that push by telling him to do something.’

‘She had a sensibility and an awareness that he didn’t have,’ David recalls. ‘Kusha was always quietly assisting someone who just lost a partner or a child or a parent. Or she was in attendance to a number of people who were dying. It was something she did, to participate, to share. And that’s where they connected, participation, that sharing is the background of this window.’

‘For me the window says that there’s no time for hate. We will reach out in love no matter what happens,’ says Barbara Cross. ‘He was ahead of his time,’ she says of John Petts ‘The way it’s saying “stop the violence, stop the murders.” The window speaks volumes about forgiveness.’

Forgiveness is a practice that has shaped Barbara Cross’ life since that dark day sixty years ago.

‘It’s symbolic that our lesson that day in church was “A Love that Forgives.” Because I hate what they did to us, but I can separate the deed from the person that did it. I wasn’t taught to hate.’

The dark shadow left by the bombing is unlikely to ever fully recede from Barbara’s life, she still feels its impact to this day.

‘If I hear loud noises, it bothers me, because I remember that sound. I’ll never forget it,’ she says. ‘I get emotional, but I must be able to share this history through my tears.’

For a long time, she didn’t like discussing the bombing in public, her nerves had suffered terribly and she shook for years afterwards. Thinking of the classroom task given to her by her Sunday school teacher that day, she takes a deep breath.

‘That writing assignment saved my life.’

Her father, the Reverend John Cross also bore the burden of that day until his death in 2007. In the later stages of his life, Barbara had been his caregiver.

Blaming himself for the bombing and for allowing Dr King and the civil rights movement to make the church the centre of its activities in Birmingham, the three trials held many years after the incident itself and the delayed justice for the victims took their toll on John Cross. Barbara says in his older years he would cry a lot.

“I think he had nightmares,” she says. ‘But I told my dad,” ‘You were courageous because if it wasn’t your church it would have been Dr King’s Church or anybody’s church. You knew that Dr King was trying to make a difference.’ I was so glad I had a chance to tell him that before he died.”

The events of September 15th 1963 are seared into America’s history, forever branding a moment of deep shame on its timeline.

“I like to think they are angels of change,” Barbara Cross says of her four classmates, none of whom lived beyond the age of 14. For the connection forged that day between her community and the people of Wales, she is thankful.

“We live in this huge world. And when you can bridge the gap between different nationalities or races, I think that’s beautiful. It shows love in action.”

A rekindling of that love and of Wales’ artistic relationship with Birmingham is currently underway. A partnership between the church and Wales’ youth organisation, The Urdd was established in 2019 and a virtual choir made up of young people from Wales and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) was formed during 2020’s Coronavirus lockdown, their online performance providing some much needed positivity during a difficult time the world over. The Urdd choir visited Alabama in 2022, performing at the University and the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church. Their visit was recently reciprocated, with the UAB choir performing at the Urdd Eisteddfod in Denbigh and at the Senedd in Cardiff Bay this summer. Connections between Aberystwyth University and the University of Alabama in Birmingham have also been strengthened, with a study exchange programme now in place. And this week, Wales’ Economy Minister Vaughan Gething and Birmingham’s Mayor, Randall Woodfin have reaffirmed the historic connection by signing a new International Friendship Pact.#

Links between two nations brought about by an artistic response to a very human tragedy.

‘The messaging behind the Wales window is timeless really,’ says Michael Petts. ‘It’s still totally relevant. It’s very powerful, really straightforward and no nonsense. It might be 60 years old, but it’s just as relevant now, if not more so.’

As an artist, John Petts was acutely aware of his work’s legacy.

‘There are cathedrals with stained glass windows which were put in in the fourteen hundreds. And the fact that he was part of that tradition meant that he was absolutely fastidious about doing a really good job,’ Michael Petts says. ‘He made sure that absolutely everything was done properly because it was going to last hundreds of years. So he was fully aware of, I would say constantly aware of the legacy that he was leaving.’

When John Petts passed away in 1991, the then Pastor of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, the Reverend Chris Hamlin sent a note of condolence to Kusha Petts. She responded in her usual thoughtful manner with a poem she’d titled ‘Day by Day.’ Words intended to comfort in a time of grief. She wrote:

‘The Moment is Forever

as it flies

Future, Past and Present

being one.’

As world events continue to demonstrate, John Petts’ Wales Window, a much loved symbol of hope and change was never intended as a final statement, an end to the conversation about how we treat our fellow human beings. Progress is not a linear force marching ever forward towards an endlessly bright future. Civil rights and liberties are hard won and to be closely guarded.

‘For me the window is about doing the right thing and not being afraid of the consequences of that,’ Michael Petts says. ‘It’s a message about vigilance. Never be complacent about the human condition and the absolute atrocities that can and do happen through negligence toward each other.’

A meaning both John Petts and the Reverend John Cross understood all too well.

A version of this essay was originally published in Home to You: 10 Years of Wales Arts Review, which is available to buy here.