David Cottis reflects on the National Theatre’s recent production of a new play by Jack Thorne which explores Richard Burton’s 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet, The Motive and the Cue.

By an odd coincidence, both large auditoria at London’s National Theatre are currently occupied by new plays about real people and (fairly) recent history. In the arena-styled Olivier, there’s Dear England by James Graham, which tells of England footballer/manager Gareth Southgate’s redemptive journey from a missed penalty in 1996 to the 2022 World Cup, while the proscenium-arched Lyttelton hosts Jack Thorne’s The Motive and the Cue, about the 1964 Broadway production of Hamlet directed by Sir John Gielgud and starring Richard Burton.

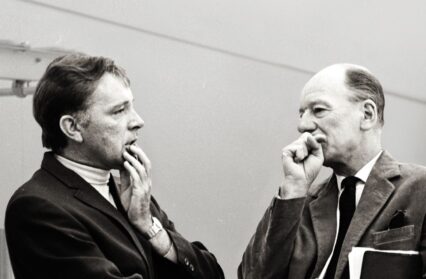

Both plays deal with the weight of history; in Dear England, Southgate, like all England managers, carries the burdens both of the 1966 World Cup triumph, and the nearly sixty years of hurt which have followed it. In The Motive and the Cue, Johnny Flynn’s Burton, one of the biggest movie stars in the world, and newly married to Liz Taylor (Tuppence Middleton), has to deal with the challenge of being directed by Gielgud (Mark Gatiss), the greatest Hamlet of his own, prewar, generation. The Motive and the Cue is inspired by two books; Letters from an Actor by William Redfield , who played Guildenstern, and is himself portrayed in this play by Luke Norris, and the clumsily-titled John Gielgud Directs Richard Burton in Hamlet, by Richard L. Sterne who, showing remarkable dedication to history, hid in the theatre to eavesdrop on rehearsals.

Burton makes an easy case study for the pop psychologist: left motherless at two, and with an unreliable, hard-drinking father, he was raised largely by his sister, then was in effect adopted by, and took the name of, his schoolteacher Philip Burton. He spent much of his life under the influence of various substitute father figures, most notably the actor/playwright Emlyn Williams. Hamlet, a play partly about the nature of fatherhood, is an obvious arena in which to play out these tensions, although at the start Burton’s attitude to Gielgud, his metaphorical father, seems to be not so much that of Hamlet as of Oedipus. The two men clash over interpretation in the rehearsal room, a battle set neatly across a series of oppositions: classical/modern, theatre/film, gay/fiercely heterosexual, English/Welsh – at one point Gielgud refers to ‘the Welshman’s worrisome bluntness sailing up the River Severn’.

In the end, it’s Elizabeth Taylor, bored in her hotel room, who brings the two men together, acting as go-between and finding a curious empathy with Gielgud as people whose greatest achievements might be behind them – he played King Lear in his twenties, she was a film star at twelve. The breakthrough comes in a rehearsal scene where Burton realises that his Hamlet, unlike Gielgud’s, didn’t like his father, which gives him motive and cue to find a new reading of the ‘To be or not to be’ soliloquy. Here, as surprisingly often, Thorne lets Shakespeare do the heavy lifting; both this climactic moment and the first-act curtain – Gielgud reciting Hamlet’s advice to the players – are cover versions.

The central three actors all have to deal with the challenges of playing modern icons, with the men having to suggest two of the most distinctive voices of the last century. To me, Flynn’s Port Talbot purr always sounds a bit effortful, more an impersonation than a performance. Gatiss is more relaxed, although the playwright, and the theme of the play, make Gielgud out to be more melancholic than he probably was – apart from one brief, quickly dispelled moment, the actor’s notorious tactlessness doesn’t appear in this play. The American cast and setting remind us that all three principals, like Hamlet himself, are outside their normal contexts and comfort zones. At one point, Gielgud’s young female assistant suggests that she’d like to direct Ann Jellicoe’s The Knack, providing a third alternative to both Gielgud’s classicism and Burton’s angry young maleness (although in an odd failure of research, Thorne has Gielgud refer to Jellicoe as Welsh, which she wasn’t).

At its root, The Motive and the Cue is a much smaller and (ironically) less theatrical play than Dear England. That, as its title suggests, is a state-of-the-nation play, pondering whether that team’s sporting difficulties may be part of a wider national identity crisis. Here, the stakes are lower, and clashes between individuals are more important than their context. It’s also a play that’s more specifically about its own subject – where Dear England is only tangentially about football, The Motive and the Cue is definitely about theatre, to the extent that one scene depends for its full effect on a familiarity with Titus Andronicus. It’s a play that was clearly programmed with a West End transfer in mind, and is getting one.

In the end, the Gielgud/Burton production went on to be a smash hit, and the longest-running Hamlet in Broadway history. It was recorded on film, and is now available on DVD. Ironically, Burton’s Hamlet, seen at the time as triumph of naturalism, now seems highly mannered, and a lot less modern than the audio recordings of Gielgud playing the same part. A projection at the end of this play tells us that over 200.000 actors have played Hamlet. In this context, The Motive and the Cue, despite Sam Mendes’ rather flat production, comes across as another reading of that play, asking some interesting questions about both real and metaphorical fatherhood, and answering at least some of them.

The Motive and the Cue transfers to the West End in December.