Craig Austin explores the multi-faceted career of the band Savages, and the messages behind their most recent album, Silence Yourself.

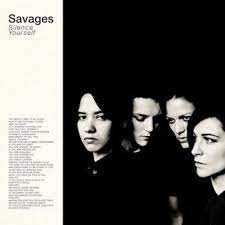

The stark, matt, monochrome sleeve of Savages’ album Silence Yourself is adorned with the text of a self-titled spoken word piece bemoaning how ‘the world used to be silent’ and how ‘now it has too many voices’, a sentiment less diplomatically expressed by its flagship single ‘Shut Up’. Yet despite being released in the same year that David Bowie shattered our sleepwalking cultural sloth with a wholly unexpected overnight blitzkrieg of impeccably sequestered bunker-crafted supremacy, the simple concept of a band that similarly seeks to cloak its seclusion and mystique within the framework of its art remains an atypical and jarring peculiarity.

A recent Guardian interview with the band, (a borderline-fatuous shakedown of indeterminate motivation), sought to paint them as little more than a sulky cabal of joyless, ungrateful party-poopers. It was a peculiarly passive-aggressive piece that focused as much on the band’s supposedly studied aloofness and their stated aversion to the contemporary live music plague of the mobile phone as exasperating rinky-dink camera, as it did the brooding majesty of the band’s début album and formidable live show. We have never been a nation that unambiguously embraces the emergence of any kind of breakthrough artistic virtuosity, often seeking instead to focus upon the petty periphery or perceived notions of preferentialism, and the recent idle accusations of ‘hype’ that have been hurled at Savages are as predictable as they are unjust, a self-satisfied knee-jerk reaction to the new cultural order on a par with the tiresomely lank-haired hippy notion of ‘selling out’.

Silence Yourself is an album that follows an artistic and stylistic model last executed – successfully, at least – by The Holy Bible-era Manic Street Preachers. A detached and template-setting inaugural sample of ambiguous dialogue giving way to a squall of controlled and menacing guitar and a procession of tightly-weaved self-contained melodramas in thrall to the British post-punk monarchy of Siouxsie and the Banshees and Joy Division. An unattended consignment of inflammable fireworks and loose Swan Vesta wrapped up in a paraffin-soaked shroud of steely harmonic vibrations and austere aesthetics. Jehnny Beth’s breathlessly heart-stopping vocals have been routinely compared to those of the ice queen herself, Siouxsie Sioux, and given that Beth sounds a LOT like La Sioux the comparison is on occasions an uncannily palpable one.

In Silence Yourself, this is not a voice or a sound borne of either the embryonic ramshackle Banshees or the acid-tinged carnival act of the mid-1980s however. Instead, Savages reinvent the finest elements of the blistering voodoo witchcraft of Juju and its attendant overtones of claustrophobia and brutal urgency, an uncompromising and relentless offensive spearheaded by a voice that has the power to unnerve and empower in equal measures: ‘She will open her heart / She will open her lips / She will choose to ignite / And never to extinguish’.

Up-lit and in-the-round, the Savages live experience is a performance even more intensely utilitarian than its recorded counterpart. Incongruously booked to play a nightclub venue most famous for its longstanding affiliation with the dance and hip-hop scene, the band are barely visible to the majority of the tangibly expectant audience, the exception being the brave few who clamber atop a scattering of towering bass bins in a bid to peer into the whites of the eyes of the noble young Savages.

A select few gaze down upon this transient amphitheatre from an overcrowded balcony vantage point, its inadvertent emperor one Polly Jean Harvey who overlooks proceedings with the engrossed expression of the recently converted. Tonight she is a fan, a fan with a camera phone. A woman who clearly didn’t get the memo, but whose lofty legacy of raw femme-centred introspection is evidently in eminently capable hands. When Beth stares resolutely ahead during the captivating bleak imagery of ‘Strife’ and conjures up a place ‘where furies smite young slits’, the memory of Polly’s own early forays into the unsettling collision of sex and death are immediately redolent.

Likewise, ‘City’s Full’, a tale of ‘skinny pretty girls’ and vacant compulsive love is given the full Patti Smith treatment, a lonely celebration of the imperfection of it all. ‘I love the stretch marks on your thighs’, she intones. ‘I love the wrinkles around your eyes.’

As much as Savages might present an image that seeks to exist in the shadows of pop culture, their discordant symphony ‘the distant rhythm of an angry young tune’, this is both a band and a record that emanates the beguiling self-confidence of having created something of immense power and a dark beauty. As for Silence Yourself, ‘This album’, as its own sleeve-notes betray, ‘is to be played loud and in the foreground.’

You might also like…

It’s a tried trope in criticism of visual arts to encourage slowness, but artists rarely give reason or device to linger. Upon receiving the second £5,000 Wal Pawb Commission at Tŷ Pawb, artist Kevin Hunt gives said reason and device, diligently, with a multi-faceted intervention, Face-Ade. Bob Gelsthorpe takes a look.

Craig Austin is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.