Professor Daniel G. Williams of Swansea University delivered the inaugural #WalesinKolkata Lecture at the British Council library in January. Here Wales Arts Review presents a fascinating journey through the deep Welsh connections in India that begins in 1783, and brings in some surprising characters along the way.

The Sanscrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the form of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three without believing them to have sprung from some common source.

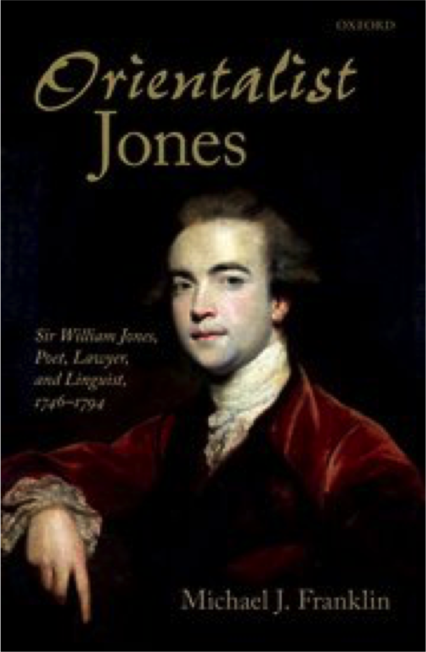

These words are by William Jones (1746-94), a Welshman buried among the captains of Empire at South Park Street Cemetery, a place that reminds the visitor that Kolkata was both the capital of India until 1912 and the second city of the largest Empire the world has ever known. In 1783, William Jones gave up his career as a circuit judge in Wales and set sail for India. As the quotation above suggests, he became a scholar of ancient Indian texts and languages, founding the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784, and discovering a deep structural relationship between European and Indian languages. Disdaining notions of racial superiority, he disseminated his discoveries with Bengali intellectuals, while at the same time ‘domesticating the Orient’ and, in Edward Said’s influential words, ‘turning it into a province of European learning’.

Apostrophised as ‘Accomplsh’d Jones’ in a contemporary poem on ‘The Restoration of Learning in the East’, that act of ‘restoration’ was predicated on the paternalistic assumptions that informed the founding of ‘Orientalism’ and formed the cultural basis for colonisation. The duality of Jones’s legacy reflects broader truths about the place of Wales within the British Empire as manifest in our nation’s relationship with India. Powis Castle, near Y Trallwng / Welshpool in mid-Wales holds a remarkable collection of Indian treasures, collected by one Henrietta Herbert (wife of Edward Clive, Governor of Madras, and daughter-in-law of the infamous robber-baron Robert, ‘Clive of India’) following a journey to South India in 1798.

Apostrophised as ‘Accomplsh’d Jones’ in a contemporary poem on ‘The Restoration of Learning in the East’, that act of ‘restoration’ was predicated on the paternalistic assumptions that informed the founding of ‘Orientalism’ and formed the cultural basis for colonisation. The duality of Jones’s legacy reflects broader truths about the place of Wales within the British Empire as manifest in our nation’s relationship with India. Powis Castle, near Y Trallwng / Welshpool in mid-Wales holds a remarkable collection of Indian treasures, collected by one Henrietta Herbert (wife of Edward Clive, Governor of Madras, and daughter-in-law of the infamous robber-baron Robert, ‘Clive of India’) following a journey to South India in 1798.

In the 1870s, industrialist Richard Glynn Vivian – the fourth son of the owners of the most successful copper smelting plant in the world – departed to foreign shores from Swansea, equipped with a sketch-book and camera. His diaries document his journeys from Sri Lanka to Madras and then on to Bombay. The field of Celtic studies, since its nineteenth-century formation, has been characterised by occasional comparative forays into tracing the similarities between ancient Vedic myths and Celtic legends and the Victorian era saw a host of Welsh missionaries and educators make their various pilgrimages to conquer the hearts, minds and souls of South Asians, as recounted most powerfully in Nigel Jenkins’s (1949 – 2014) magnificent and troubling travelogue Gwalia in Khasia (1995). The melody ‘Bryniau Casia’ remains in the hymn books of Welsh nonconformists to this day (check our Lleuwen Steffan’s version on Duw a Ŵyr [Sain, 2010]), and Thomas Jones, the instigator of the ‘biggest overseas venture sustained by the Welsh’ – a venture that turned hundreds of Khasis into hymn-singing Presbyterians – is buried in the Scottish Cemetery at Karaya Street in Kolkata.

The Brecon-born educationalist and medic Frances Hoggan (1843 – 1927) sought to ameliorate the suffering of India’s poor through Western medical practices and dissemination of the English language. Gandhi would come to see both the English language and Western medicine as underpinning the ‘enslavement’ of his people, and the ferocity of his critique indicates the extent to which Western medical ideas had been adopted in India, and highlights both the success of Frances Hoggan’s desire to disseminate medical practices and the contradictory legacy of such reformist activities. Gandhi turned to Wales in order to illustrate his point, and expressed his admiration for ‘the great efforts being made to revive a knowledge of Welsh among Welshmen’.

The first English language biography of the Bengali poet, educationalist and artist Rabindranath Tagore, was written by the Anglo-Welsh author Ernest Rhys (1859-1946) who compared Indian ragas with the Welsh folk tradition of cerdd dant. Welsh nationalists, from Ambrose Bebb to Waldo Williams, drew much from the non-violent anti-Colonial politics of Gandhi. More recently the Swansea Valley-based curator and art historian at the Courtauld Institute of Art, Zehra Jumabhoy, has redefined our understanding of Modernism in Indian art and its relationship to national identity. Today Indian industrialists are vital contributors to a fragile Welsh economy – the Tata Steel works in Port Talbot is owned by an old Bombay family. As with much else when it comes to Britain’s acknowledgement of Wales, many of these connections are overlooked in the accepted narratives. The Wales-India project has offered a viewfinder for bringing some of these connections back into focus, for exploring their conflicted implications and for developing lines of cultural dialogue and debate.

In this lecture, I’m going to try and weave another web of connections; connections that are historically timely given the global rise of Far-Right movements and their politics of intolerance, and relevant to our visit as I’m here with Dr. Elaine Canning representing Swansea University and the International Dylan Thomas Prize. ‘Light, Ladd and Emberton’ are performing their magnificent evocation of Caitlin Thomas’s life as part of this visit, and it’s with Caitlin Thomas that I’m going to begin. Francesco Fazio, her son with a later husband, argued that:

My mother Caitlin had a lot in common with Sylvia Plath. They both made suicide attempts. They both married men who were the most famous poets of their day. They both lived in their shadow and gave up their own work to sustain their men’s art. These women suffered so much and have so much to tell. But their husbands were so egotistical that they didn’t let the women tell their story.

Whatever we wish to make of the comparison, there is no doubt that Plath was a great admirer of Dylan Thomas. The narrator of Plath’s semi-autobiographical novel The Bell Jar tells us that she loves Dylan Thomas, and was reading his work in the summer of 1953, a summer – as we’re told in the novel’s opening – that was ‘queer’ and ‘sultry’, it was

the summer that they executed the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York. I’m stupid about executions. The idea of being electrocuted makes me sick, and that’s all there was to read about in the papers.

This was the context in which Dylan Thomas made the last two of his American visits in 1953. The Rosenbergs (to whom I shall return) were executed on June 19th. Dylan was to die in New York on the 9th of November. What I think is often missed in accounts of Dylan Thomas’s visits to America is the highly fraught political context of the time, and the political radicalism that Thomas communicated in his readings. In his lecture ‘A Visit to America’ he spoke of the ‘prejudiced procession of European lectures’ travelling across the USA, including not only ‘fat poets with slim volumes’, but also ‘men from the BBC who speak as though they have the Elgin marbles in their mouths’, and ‘brassy bossy men-women with corrugated iron perms and hippo hides who come self-announced as “ordinary British housewives” to talk to rich minked chuncks of American matronhood about the iniquity of the Health Service, the criminal sloth of miners, the visible tail and horns of Mr Aneurin Bevan’.

Aneurin Bevan (1897 – 1960) was a leading minister in Clement Attlee’s post-war Labour government, a self-described ‘projectile discharged from the Welsh valleys’ to represent the interest of the working class. Attlee’s government would largely oversee the dismantling of Empire – India achieving its Independence in 1947, of course – and embarked on a programme of radical policies at home, not least the establishment of the National Health Service led by Bevan himself, which made him a hero of the Left and vilified by the political Right in Britain and the United States.

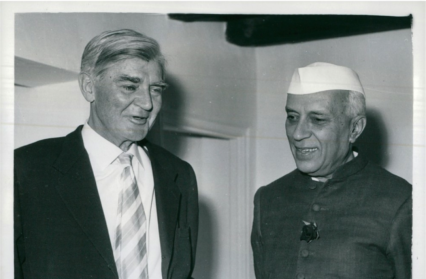

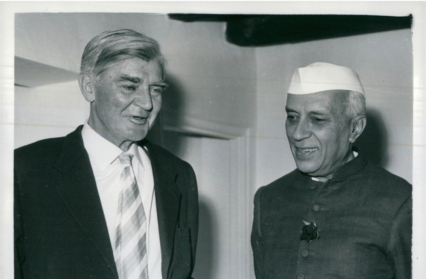

While Dylan Thomas was referring to Aneurin Bevan in his speeches, Bevan himself was in India in March 1953. Bevan developed a friendship with Jawaharlal Nehru (1889 – 1964) that was to last until the end of his life. During his first visit to India, Bevan asked to be taken to see the Himalayas. He noted that ‘as the peaks of the Himalayas unfolded their chaste loveliness before us I was almost seduced from my allegiance to my favourite view of the Black Mountains and the Brecon Beacons above Tredegar’. During that visit Bevan had controversially suggested that a third bloc of nations would be needed to hold the balance of power between the American and Russian nations that were both ‘hagg-ridden by fear’. In the United States that fear was manifested explicitly and tragically in the case of the Rosenbergs.

*

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were American citizens executed for conspiracy to pass information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union. Communists and left-leaning artists such as Nelson Algren, Bertolt Brecht, Dashiell Hammett, Frida Kahlo and Dylan Thomas protested the position of the American government. In galvanising the Left, the comparison made in America was between the Rosenberg trial of the 50s and that of two Italian Anarchists, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, executed in the 1920s.

Sacco and Vanzetti were Italian-born anarchists, convicted of murdering a guard and a paymaster during the armed robbery of a shoe factory in Braintree, Massachusetts in 1920. They were executed in 1927. In that case as well, celebrated writers, artists, and academics pleaded for their pardon or for a new trial. If anti-Italian prejudice and opposition to Anarchism informed the executions in the 1920s, then anti-Semitism and a virulent anti-Communism were seen to have played a decisive role in the Rosenberg case. (The whole era is brought to life in E L Doctorow’s novel of 1971, The Book of Daniel).

Sacco and Vanzetti were Italian-born anarchists, convicted of murdering a guard and a paymaster during the armed robbery of a shoe factory in Braintree, Massachusetts in 1920. They were executed in 1927. In that case as well, celebrated writers, artists, and academics pleaded for their pardon or for a new trial. If anti-Italian prejudice and opposition to Anarchism informed the executions in the 1920s, then anti-Semitism and a virulent anti-Communism were seen to have played a decisive role in the Rosenberg case. (The whole era is brought to life in E L Doctorow’s novel of 1971, The Book of Daniel).

The trial of the Rosenbergs began on March 6, 1951 and it brought the Sacco and Vanzetti case back to mind of the American Left and Liberal intelligentsia – the type of people who turned up to hear Dylan Thomas reading. Thomas noted in a letter that ‘the murder of the Rosenbergs should make all men sick and mad’. Dylan would often read works by poets other than himself on his tours, and was particularly generous to his Welsh contemporaries. He would include poems by Lynette Roberts, Ken Etheredige, Idris Davies, Vernon Watkins and, most relevant for this lecture, Alun Lewis in his public readings of this era. Alun Lewis, from Cwmaman in south Wales, committed suicide while serving in India in 1944. He left a body of poems, short stories and a recently discovered novel behind him, in some of which he responds poetically to his time as a soldier in India. In introducing Alun Lewis, Dylan Thomas described him as

a healer and illuminator, humble before his own confessions, awed before the eternal confession of love by the despised and condemned inhabitants of the world crumbling around him. … He knew, like Wilfred Owen, that, in war, the poetry is in the pity. And, like Owen, he could never place himself above pity but must give it tongue. Here is an extract from an unfinished play in which Sacco, the comrade of Vanzetti, writes from prison to his son.

And so in the year of his own death, in the context of Joe McCarthy’s anti-Communist witch-hunts in America, in the America that was denying the socialist African American singer Paul Robeson a passport to travel, and was about to execute Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Dylan Thomas read Alun Lewis’s poem ‘Sacco Writes to his Son’. It is not a typical poem by Lewis. But it is a poem that illustrates the healing compassion that Thomas detected in his Welsh contemporary’s work:

And for yourself, remember in the play

Of happiness you must not act alone.

The joy is in the sharing of the feast.

Also be like a man in how you greet

The suffering that makes your young face thin.

Be not perturbed if you are called to fight.

Only a fool thinks life was made his way,

A fool or the daughter of a wealthy house.

Husband yourself, but never stale your mind

With prudence or with doubting. I could wish

You saw my body slipping from the chair

Tomorrow. You’d remember that, my son [.]

I can’t help but feel, then, that to read this poem in America in 1953 was a politically deliberate act.

If Dylan Thomas was reading Alun Lewis’s poem based on Sacco’s letter to his son as a protest against the execution of the Rosenbergs, a poem directly about the Rosenberg case was being composed in Hyderabad prison in Pakistan.

The author was Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911 – 1984), one of the most celebrated of all Urdu poets. Born in Punjab, British India, now Pakistan, Faiz served in the British Indian Army and was awarded the British Empire Medal. After Pakistan’s independence, Faiz became the editor of The Pakistan Times and was a leading voice of the political Left. He was arrested in 1951 for allegedly playing a part in an attempt to overthrow the Pakistani administration and replace it with a left-wing government. Faiz was released after four years in prison and went on to become a notable member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement and eventually an aide to the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto administration. Following Buhtto’s execution in 1979, he went to live in a self-imposed exile in Beirut. Faiz was an avowed Marxist, receiving the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet Union in 1962. He returned to Pakistan in poor health in 1982 and died in 1984.

The author was Faiz Ahmed Faiz (1911 – 1984), one of the most celebrated of all Urdu poets. Born in Punjab, British India, now Pakistan, Faiz served in the British Indian Army and was awarded the British Empire Medal. After Pakistan’s independence, Faiz became the editor of The Pakistan Times and was a leading voice of the political Left. He was arrested in 1951 for allegedly playing a part in an attempt to overthrow the Pakistani administration and replace it with a left-wing government. Faiz was released after four years in prison and went on to become a notable member of the Progressive Writers’ Movement and eventually an aide to the Zulfikar Ali Bhutto administration. Following Buhtto’s execution in 1979, he went to live in a self-imposed exile in Beirut. Faiz was an avowed Marxist, receiving the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet Union in 1962. He returned to Pakistan in poor health in 1982 and died in 1984.

During his time in prison in the early 1950s Faiz found himself writing more poetry than he had in the previous years. His jailers permitted him not only to write the poems, but also to read them to other inmates twice each month. His English wife Alys (an interesting figure in her own right) was permitted to take the poems back on one visit, duly stamped ‘approved’ by the censors. She would recall the journey into the Sindh desert to visit her husband: ‘So this was Hyderabad and these were the grey prison walls, and here in the compound was the whipping post. I was to grow to know it all so well.’ Faiz’s volume Dast-e-saba (hand of breeze) was published in 1953; the year in which Dylan Thomas (and Joseph Stalin) died, in which Aneurin Bevan visited India and Pakistan, and in which the Rosenbergs were executed. Among his prison poems there is one written, Faiz tells us, ‘After reading the letters of Julius and Ether Rosenberg’. This is a translation of the poem ‘Hum jo tareek raahon mein maare gaye’ (We who were executed on dark highways):

I longed for your lips, dreamed of their roses:

I was hanged from the dry branch of the scaffold.

I wanted to touch your hands, their silver light:

I was murdered in the half-light of dim lanes.And there where you were crucified,

so far away from my words,

you still were beautiful:

color kept clinging to your lips –

rapture was still vivid in your hair –

light remained silvering in your hands.When the night of cruelty merged with the roads you had taken,

I came as far as my feet could bring me,

on my lips the phrase of a song,

my heart lit up only by sorrow.

This sorrow was my testimony to your beauty–

Look! I remained a witness till the end,

I who was killed in the darkest lanes.It’s true – that not to reach you was fate–

but who’ll deny that to love you

was entirely in my hands?

So why complain if these matters of desire

brought me inevitably to the execution grounds?Why complain? Holding up our sorrows as banners,

new lovers will emerge

from the lanes where we were killed

and embark, in caravans, on those highways of desire.

It’s because of them that we shortened the distances of sorrow,

it’s because of them that we went out to make the world our own,

we who were murdered in the darkest lanes.

Somewhat like Alun Lewis’s poem on the Sacco and Vanzetti trial, Faiz’s poem in response to the Rosenburg case is a tribute to the persistence of love in the face of death.

The first book of Faiz’s poetry in English translation appeared in 1989. The collaboration for these translations began in 1979, when Faiz and American poet Naomi Lazard met at a writers conference in Honolulu. Lazard quoted a line to Faiz from Anglo-Celt Robert Graves’s long mythopoetic volume The White Goddess (1948). The quotation, received by Graves in a letter by Alun Lewis, noted that ‘the true subject of poetry is the loss of the beloved’. According to Naomi Lezard, Faiz laughed his famous throaty laugh upon hearing these words, before noting that it was he who had originally passed on that particular Sufi teaching to Alun Lewis. Alun Lewis and Faiz Ahmed Faiz had been soldiers together during the Second World War. Faiz had served as a Captain in the British Indian Army alongside his Welsh contemporary in Burma.

There is no correspondence between them, and were it not for the conversation with Naomi Lezard, it is unlikely that we would know that Lewis and Faiz had met. But now that we do know, is there not an echo, a strain of influence, linking Lewis’s poem on Sacco and Vanzetti, read by Dylan Thomas in America, to Faiz’s poem on the Rosenbergs? Today, as Welsh and South Asian histories and cultures connect in the sun of Kolkata, as dark clouds loom over the world’s politics, I don’t think it is too fanciful to suggest that these poets were also connected as they walked some of the darkest lanes of the twentieth century, singing of the loss of the beloved in the face of political incarceration and injustice.

In November Dr Zehra Jumabhoy of the Courtauld Institute, Katy Freer of the Glyn Vivian Gallery and Professor Daniel G. Williams will be arranging a conference on South-Asia and Wales at the Glyn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea.. ‘Imperial Subjects: (Post)colonial conversations between South Asia & Wales’ will take place on the 1 and 2 of November 2019. A call for papers has been published here.

This lecture was part of Wales in Kolkata, a season of Welsh arts activity and collaboration taking place in Kolkata this January. Supported by Wales Arts International and the British Council, Wales in Kolkata is a result of the relationships and networks formed by the 2017/18 #IndiaWales season, a major programme of artistic collaboration between Wales and India.