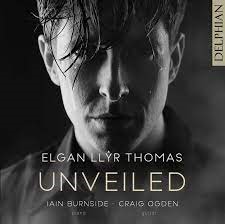

David Truslove listens to Unveiled, the first solo release from Welsh tenor Elgan Llŷr Thomas.

The release of Unveiled is a big moment for Elgan Llŷr Thomas (born 1990), marking his first solo release. In curating an album in which he feels a connection with its themes of hidden love, shame and pride, the compilation explores LGBTQ representation in vocal music through some of the UK’s most iconic gay composers and poets, as well as marginalised artists. In an interview with Claire Seymour (Opera Today) Thomas commented ‘I realised that I needed to record an album that would let listeners into my world – would open up the things that I am interested in and that make me the person I am’. This world, as Lucy Walker’s liner notes clarify, ‘traverses a history of male homosexuality from necessary discretion to the (relatively) liberated present’.

Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett were always going to be obvious choices for this debut disc. But Thomas has also included premiere recordings of music by Ruth Gipps whose four songs set verses by the Great War poet Rupert Brooke. A single song by W. Denis Browne reminds us of his association with Brooke and his presence at the poet’s death at Gallipoli in April 1915. Finally, there is a cycle of songs by the soloist as composer, with a singular reference to Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. Regrettably, for copyright reasons, the texts are not included in the booklet, and likewise for Tippett’s trio of songs. Delphian does, however, include the texts of new English versions of Britten’s Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo conceived by Jeremy Sams, replacing those by Elizabeth Mayor and Peter Pears in the 1943 Boosey & Hawkes edition. These translations carry a less ambiguous message, one that provides an obvious clue to the disc’s title Unveiled.

There is nothing remotely ambiguous about Thomas’s jewel-like tenor, an authoritative voice of considerable stature that could carry with ease across his hometown of Llandudno. There are echoes of both Pears and Robert Tear in the clarity of execution and the communication of emotion. At times, it’s a no-holds-barred sound that can knock you sideways, with a ringing upper register sounding over-egged, even strenuous. But there’s real energy and passion in the voice, nowhere more discernible than in the Michelangelo sonnets. Premiered by Britten and Pears at the Wigmore Hall in September 1942, these declamatory love songs date from the composer’s self-imposed exile in America during the early years of the Second World War. Bearing in mind homosexual love was still a criminal offence, the ardour of Britten’s songs – plainly directed at Pears – was camouflaged by the original Italian texts. Emotions are even more transparent in this new version, where shared love is a ‘field of gold’ and the object of the poet’s longing is the ‘ne plus ultra of Creation’. Secrecy and frustrated desire are unambiguous in the feverish setting of ‘Sonnet LV’ where emotions ‘must be hidden’. Thomas pours his heart and soul into these songs; wonderfully tender in ‘Sonnet XXX’, elsewhere fiery, lovelorn and adoring, movingly so in the final song when his singing of the ‘flawless face I love so dearly’ is beyond beautiful.

From the same year as Britten’s cycle (1940) comes Ruth Gipps’s Four Songs of Youth. The first, ‘Failure’, with its sheer weight of sound can be wearying, its decibels denying warmth. Yet, there’s no denying Thomas’ involvement with the agonised spirit of Brooke’s verses or the assurance with which he negotiates Gipps’ dramatic vocal lines with their awkward upward leaps, most notably in ‘The Dance’. If Thomas tends to go full tilt here, a more gratifying tone emerges in the resignation of ‘Unfortunate’ and too in the savage attack on lost youth that is ‘Peace 1914’ where he achieves a lovely mezza-voce at ‘into swimmers cleanness leaping’. Coming as a breath of fresh air is W. Denis Browne’s To Gratiana dancing and singing (1913), setting words by the Cavalier poet Richard Lovelace (1618-1657). Browne recreates the intensity of the grieving poet’s experience as he and other men watch the captivating but unattainable Gratiana, reflecting on her charms as ‘Each step trod out a lover’s thought’. It has been suggested that the song was written by Browne directly to Brooke as an expression of his love.

To the Songs for Achilles (1961) Thomas fashions an exceptional performance, drawing attention to Tippett’s bravura vocal style, one at odds with the more intimate guitar accompaniment. Premiered by Peter Pears and Julian Bream, these homoerotic songs are sung here with remarkable passion and precision, their melodic angularities (not the most user-friendly of vocal contours) fearlessly dispatched. There’s no mistaking Thomas’s sustaining power or sense of yearning within ‘In the Tent’ where his voice can both melt hearts and burn like an acetylene torch. The battle cries of ‘Across the Plain’ are no less commanding, and the concluding ‘By the Sea’ brings relief in its lamenting for the death of Patroclus, closing with an exquisitely rendered top B flat. Sensitive support is provided by Craig Ogden’s bewitching guitar, the accompaniment’s rigorously detailed part handsomely rendered.

Setting short poems by Andrew McMillan, Thomas refers to his own fourteen-minute song cycle, Swan, as a ‘mini opera’, its accessibility described as ‘offering some familiarity in harmonic terms’. To my ear they bring faint echoes of the heightened expressivity of Britten whom Thomas clearly reveres. The cycle relates the story of Swan Lake, with each song having its own musical style and linked by leitmotifs. While not every word is clear (and the absence of the text is irritating), an emotional arc is communicated and the watery evocations within the accompaniment are highly effective. The image of a swan (serene above water and furiously agitated beneath) seems entirely appropriate for those artists prior to a more tolerant society who had to hide their often complex personal lives under a veneer of poised respectability. No doubt, this cycle will be a much-cherished addition to the repertoire.

Throughout the disc, accompanist Iain Burnside is a sensitive and poetic collaborator with a chameleon-like ability to adapt to the varied musical characterisations within this confessional-style programme. Well worth investigating!

Unveiled is available now through Delphian Records.