Winterreise | David Truslove listens in on Ian Bostridge and Antonio Pappano give a chilling but compelling performance of Schubert’s Winterreise at the Royal Welsh College of Music and Drama.

Performing to a visibly reduced audience is likely to be a disheartening experience for any recitalist, any hall’s partially occupied seats certain to lower the emotional temperature. Yet the starkness of such an encounter is, arguably, ideal for Schubert’s 1827 Winterreise, performed last Friday evening by Ian Bostridge and Antonio Pappano in a sparsely populated Dora Stoutzker Concert Hall.

The song cycle’s preoccupation with alienation and solitude may have resonated especially powerfully for online listeners, offering them a heightened involvement within the current global pandemic. Certainly, the atmosphere in Wilhelm Müller’s bleak poems and Schubert’s almost minimalistic writings chimes readily with our own wintry isolation.

If, in these coronavirus-laden times, the connection is an ideal fit, so too is the voice and manner of Ian Bostridge where Schubert’s song cycle seems to have been written expressly for him. Since his first performance as a twenty-year old History undergraduate at Oxford, Winterreise has been central to this tenor’s life: he has presented the work for over thirty years. Indeed, few singers have explored Schubert’s twenty-four songs so exhaustively, and with over a hundred recitals (partnered by numerous internationally acclaimed pianists in world-wide tours) and three recordings to his credit, his relationship with the work is virtually unequalled in modern times. There has also been a Channel 4 film with David Alden from 1994 and, more recently, an award-winning book: Schubert’s Winter Journey: Anatomy of an Obsession.

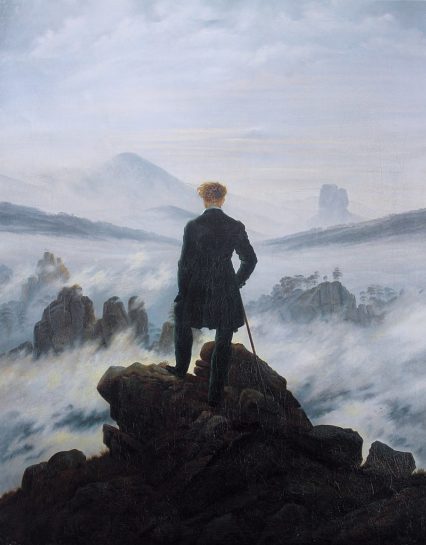

This might suggest there is no other interpreter than Bostridge for this song cycle. He seems to inhabit the very soul of a Romantic poet. Pale-faced, lithe and willowy, Bostridge paces the stage, head lowered, with all the appearance of a condemned man often seemingly singing to himself, narrowly avoiding histrionics, yet never exaggerating sentiment. Both delivery and timbre form an ideal alliance that underline the wild swings of emotion of Müller’s young man, disappointed in love and disillusioned with life. (Bostridge could have been the Wanderer above the Sea of Fog so evocatively portrayed in Caspar David Friedrich’s 1818 painting.)

For some, his idiosyncrasies come across as mannerisms but who cares, if those facial contortions, the abrupt lurching to one side or the sudden vocal stresses help define a characterisation. Winterreise is a cycle that compels restlessness, and his platform manner is part of a personal armoury of one individual confronting an intense psychological trauma. Why should we mind too if his commitment to every turn of phrase is so musical? His ability to communicate the protagonist’s disintegrating mind (veering between delusion, mocking self-awareness and nihilistic despair) is now a fully honed interpretation, sharpened across three decades.

Interpretative decisions will vary from one performer to another and Bostridge gives a haunting characterisation of what Schubert himself dubbed “a cycle of spine-chilling Lieder” and fully inhabits the diminishing world of the wanderer. Unsurprisingly, these songs have attracted a wide range of artists, from Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau’s baritone to Alice Coote’s mezzo. But for me, despite Fischer-Dieskau’s relationship with the song cycle and his seven commercial recordings, Winterreise is most closely associated with Bostridge who has made it his own.

Antonio Pappano (Music Director of the Royal Opera House) is no stranger to Winterreise either and while he hasn’t partnered Bostridge as often as Thomas Adès, he has built up a modest recording portfolio with the singer, including Schubert’s Schwanengesang and repertoire from 20th century English song. Pappano proved a sensitive and equal partner, whose own understated contribution also revealed much of the music’s character, while remaining deftly fluent. Notable throughout was his subtle balancing of the piano part’s internal voices, including his highlighting of vital secondary lines. If the dramatic contrasts of ‘Frühlingstraum’ felt unremarkable or the measured ‘Die Post’ denied any excitement (perhaps this has been overly jaunty in the past), there was much to enjoy in Antonio Pappano’s mocking staccatos of ‘Auf dem Flusse’, the sepulchral sonorities of ‘Das Wirtshaus’, and the eerie half-lights of ‘Die Krähe’, the latter wonderfully shaped by Ian Bostridge’s sinewy tenor.

His is a distinctive English sound, still gleaming at fifty-six, and on Friday, still producing a tone of pure spring water. At times his voice struggled with the lower pitches becoming grainy in ‘Gefrorne Tränen’ and audibly sinking below the radar as his voice trailed off to expressive effect in ‘Der Lindenbaum’. Earlier, we were in no doubt as to the fickle nature of love and the traveller’s emotional unpredictability evoked in the suitably accented contours of ‘Die Wetterfahne’, and in the subdued ‘Gute Nacht’ his voice swung between reluctant acceptance and resolution not to disturb his faithless lover’s sleep. ‘Erstarrung’ brought the first signs of torment from both singer and accompanist in sudden stresses and in ‘Wasserflut’ Bostridge seemed to howl with distress as the wanderer requests the snow to direct his tears past his sweetheart’s house. Elsewhere, ‘Einsamkeit’ was distinctive for its wretchedness, there was Dutch courage in ‘Mut’ and a darkening intensity gripped ‘Der Wegweiser’. By the end, a bleached tone of heartrending beauty wrapped itself around ‘Der Leiermann’, the last verse remote, defeated and drained of any life pulse. At the very end, the long silence seemed to hold a mirror to our times and within it to ask as many questions as provide answers.

David Truslove is a critic and regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.