I have lived among the English for many years, and beyond superficial differences in idiosyncrasies and attitudes, and despite English reservations, I believe these neighbour races share, like all others, the lapses into disorderliness of mind and the hidden impulses which provide the tiny, concentrated explosion short stories should contain. – Rhys Davies

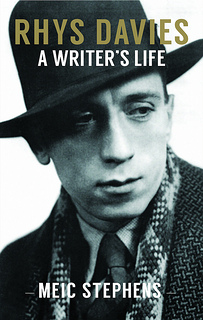

by Meic Stephens

Parthian Books, £20. 354pp.

I must confess that I had never read Rhys Davies until I came to prepare for this essay. Although I was aware of his reputation as Wales’ premier exponent of the short story, for some reason I had neither chanced upon nor purposefully settled down to read any of his works. While this is assuredly my own fault, there can be little doubt that one of the factors which contributed to this ignorance, is the odd lack of contemporary interest in Rhys Davies, to say nothing of the extremely limited number of books (from a canon in excess of forty – Davies was extremely prolific) that are currently in print.

The Parthian/Library of Wales series produced a typically handsome version of his debut novel The Withered Root in 2007. However, being particularly interested in the realm of short fiction, it was to his short stories that I most wanted to turn. To my surprise, and latterly my dismay, I found that there was only one small volume currently in print, a rather thin, if entirely excellent collection entitled A Human Condition, which had been published in 2001 to celebrate the centenary of Davies’ birth.

Within the one hundred or so pages of this marvellous if rather limited collection (considering Davies wrote in excess of one hundred stories, the republishing of a mere seven seems a little on the slim side – but this again, is perhaps indicative of his strange lack of popularity), we immediately find ourselves within a perfectly realised, stylistically idiosyncratic universe. A universe, moreover, that is quite clearly the work of a writer of the first rank.

Why then, this lack of contemporary interest in Rhys Davies? As Meic Stephens makes clear in A Writer’s Life, (which is the first full biography of Davies), in his time Davies was eulogised by everyone from Lawrence to H.E. Bates, from Betjeman to Muriel Spark. He was frequently read aloud on the BBC, while his stories appeared in all the best anthologies. He was even kept on a retainer by The New Yorker, winning the Edgar Award for the best short story published in the United States in 1966 (for ‘The Chosen One’, which had first appeared there.)

Stephen’s suggests that a large part of the reason may be that the man himself was not keen to associate himself with literary movements (he was not terribly impressed by Lady Ottoline Morrell and the Bloomsbury group, neither was he much taken with Ivy Compton Burnett and her largely homosexual set, declaring her ‘soooo boring.’) Nor was he one to actively cultivate the limelight even as he ardently craved literary success. No, he preferred to work diligently on his extraordinarily large body of work – his work ethic surely, at least in part, being a product of the hardworking Rhondda background from which he came – believing that his art was the only important thing.

Another factor, of course, in the comparative lack of attention he receives in his homeland of Wales, may well be a result of the somewhat dilettantish attitude that he could at times display towards his birthplace (his relationship with Wales was surely, as Meic Stephens says, made up of both ‘a mixture of love and hatred’ – but then, what artist doesn’t feel this attitude towards the place in which they grew up?) Here he – in a letter to a literary friend – describes a return visit to the valleys, to stay with his parents:

As you see I’m in Wales trying to persuade myself that the country is doing me good… it’s raining persistently now, the coal-dusty hills are all sopped with wet, the people are quite blank with poverty… in the nights one seems to be sucked into a cylinder of unutterable gloom. I shan’t stay long after my American advance arrives… but my people are as chirpy as ever – fat, red-cheeked, always eating and bickering with each other – it keeps them alive.

But while Meic Stephens tends to present examples like this as being indicative of Davies’ attitude towards Wales, certain aspects strike me in this and several of the other quoted passages in A Writer’s Life, as having more to do with Davies’ apprenticeship as a writer than his true feelings. Those ‘coal dusty hills… all sopped with wet’ and those ‘people… quite blank with poverty’ are clearly rehearsals for his creative work. Meanwhile the dandyish writer in him clearly can’t resist that Wildean, ‘it keeps them alive’; which, as much as anything, is probably to amuse the recipient of the letter. Indeed there is a callowness and a dandyishness to much of Davies’ early pronouncements which is entirely in keeping with the vogueish way of the Bright Young Things who populated the 1920s London that he had recently left the Rhondda for. Viewed in this light it is surely not too much to think of pronouncements like this as being just as much to do with a desire to impress as to do with truthful candour. (And Rhys Davies is a writer who was rarely on first name terms with truthful candour, something that A Writer’s Life frequently attests to.)

But for all this, it may well be true to say that Davies, in so deliberately setting himself apart from the idea of being a capital ‘W’ Welsh writer – even if many of his stories are set in his home country – may have partially alienated himself from his own people. He set out to make himself an artist free of borders and that is just what he seems to have achieved.

And, of course, this is what all artists should and must do. An artist must be defined by their work and not where they come from. Perhaps too, it is necessary to first leave a place in order to describe it, as Joyce did in order to ‘give Dublin to the world.’ (And let us not forget that Joyce was not always the national treasure in Ireland that he is today). That Davies realised this so early in his career is clearly a mark of the implicit understanding he possessed concerning what it takes to be a writer. And this being the case it is easy to understand the exasperation he showed when asked, in this interview with Keidrych Rhys in 1946, ‘whether ‘Anglo-Welsh literature should express a Welsh attitude to life and affairs, or whether it should merely be a literature about Welsh things[?]’:

Neither, consciously. If a writer thinks of his work along these lines it tends to become too parochial, narrow. But if he is Welsh by birth, upbringing and selects a Welsh background and characters for his work, an essence of Wales should be in his work, giving it a national ‘slant’ or flavour. But no flag-waving. A curse on flag-waving.

Perhaps then the main reason for Davies’ complicated attitude towards the Rhondda, and indeed Wales as a whole (and there are times when it feels as though he only views Wales through the prism of his childhood in the Rhondda), is to be found in his sexual orientation. These were difficult times to be a homosexual anywhere, and it seems reasonable to suggest – as Meic Stephens does – that a working class, Nonconformist mining community, was probably one of the more challenging places in which a young homosexual man could spend the tenure of his adolescence.

Davies himself wrote very little that was directly about his childhood and almost nothing about his homosexuality (at least amongst his surviving papers – Stephens’ task has been made all the harder by Davies losing a great deal of his letters and manuscripts in a house fire), and so it is difficult to judge exactly the kind of effect this environment had on him. However, it seems fair to assume that when he makes his more horrified comments concerning the valleys it is presumably viewed through both a sense of rejection regarding his sexuality and perhaps, also, an alarm at some of the more extreme aspects of Nonconformism that he may have witnessed.

Because there is also clearly a great deal of warmth and affection for Davies’ homeland to be found in his work, not least in his descriptions of the Welsh countryside, for which he had a poet’s eye – as we can see in this description of North Wales after heavy snowfall:

Not a boulder or streak of path showed on Moelwyn’s swollen heights. Yet close at hand there were charming snow effects. The van rounded a turn of the lane, and breaks in the hedges on either side revealed birch glades, their spectral depths glittering as though from the light of ceremonial chandeliers. All the crystalline birches were struck into eternal stillness – fragile, rime-heavy boughs sweeping downward, white hairs of mourning. Not a bird, rabbit, or beetle could stir in those frozen grottoes, and the blue harebell or the pink convolvulus never ring out in them again.

Meanwhile a story like ‘I Will Stay By Her Side’ (from which the above quote comes) contains enormous sympathy for its protagonist, an old man whose wife has just died, and who refuses to leave their home in the Snowdonia hills. Meic Stephens discusses (and appears to side with) Barbara Prys-Williams’ theory that Davies was a narcissist (an opinion his brother, Lewis Davies strongly refutes in a letter to the biographer) but the degree of sensitivity to and perception of human emotions that a story like this requires, for me, refutes this line of thinking in one foul swoop. Davies clearly relates to the old man’s right to a stay in his home, rather than be moved to the old people’s home as the local – rather pushy – nurse wants, and indeed on one level, the man can be seen as a metaphor for Davies’ belief in the inviolacy of the individual. The appearance of a hare at the end of the story is of course hugely significant – the hare being the emblem that Davies uses to represent himself, and indeed his conception of the creative process, in his semi-fictive autobiography Print of a Hare’s Foot (Prys-Williams also has a problem with the semi-fictive aspect of Hare’s Foot, clearly never having heard of Nabokov’s Speak, Memory.):

Arriving from nowhere, a hare had jumped on to the smooth track. His jump lacked a hare’s usual celerity. He seemed bewildered, and sat up for an instant, ears tensed to noise breaking the silence of these chaotic acres, a palpitating eye cast back in assessment of the oncoming plough. Then his forepaws gave a quick play of movement, like shadowboxing, and he sprang forward on the track with renewed vitality. Twice he stopped to look as though in need of affiliation with the plough’s motion. But, beyond a bridge over the frozen rivers he took a flying leap and, paws barely touching the hardened snow and scut whisking, escaped out of sight.

Here the hare acts as a manifestation of the man’s spirit, fleeing the pedantic nurse’s clutches, and maintaining his freedom. This also, of course, acts as an illustration of the way Davies conducted both his personal and his artistic life. He always cherished his independence from family life, long-term relationships and literary coteries, while steadfastly ploughing his own artistic furrow. But not only this, the hare also acts as a manifestation of those moments on, to borrow Nabokov’s phrase, ‘the highest terrace of consciousness’, which may also be described as epiphanies. A moment of perception come and gone in a second, ‘paws barely touching the hardened snow and scut whisking, escaped out of sight.’

One of the other things that elevates this story is that the pushy, pedantic nurse, is only partly those things. Davies also portrays her kindness – she feels genuine affection for the old man – and her loneliness too. Even the clergy man and plough driver are not relegated to the one dimensional. Indeed throughout the piece Davies displays an extremely acute understanding of human psychology. An understanding that, when combined with the poetic description of landscape, culminating in the epiphanic moment of the hare pausing and then leaping to freedom, represents as perfect an example of the short story as you could wish to see.

Whether the entirety of Davies’ vast oeuvre is as successful as this it will be impossible to say until more of his works become available again. Meic Stephens gives the impression that the Davies’ cannon is something of a rollercoaster ride of extreme highs, steady in-betweens and peculiar lows, including a cartoonish account of Wales and it’s people entitled My Wales, as well as the frankly bizarre-sounding seafaring epic entitled, Sea Urchin: Adventures of Jorgen Jorgensen. Either way, there can be little doubt that in writing this informative, intriguing biography, Meic Stephens has done the reading public a great service, as Rhys Davies is clearly a writer who should be read more of by people not just in Wales but everywhere.