Gary Raymond is at the National Museum in Cardiff to cast a critical eye over the exhibit War’s Hell, depicting the Battle of Mametz Wood in art.

The title of the National Museum’s exhibition commemorating the art connected to the Battle of Mametz Wood, War’s Hell, is not simply a platitude to fit all wars and so fit all minds; it is a line from the great Robert Graves poem, “A Dead Boche”, itself a stark warning against those who seek, ignorantly, glory in combat. Graves’ line is a quote, a non-artisanal bromide, so the exhibition title quotes a quote, pulls the call of the common man through the funnel of the poet. One effect of the First World War, noted perhaps more than of any other war, was to overwhelm. Overwhelmed or not, it was the job of artists – both morally and, for some, on commission – to convey the lot of the common man through these extraordinary circumstances. And that, from title on, is the essence of this ambitious, multi-faceted and thoughtful show.

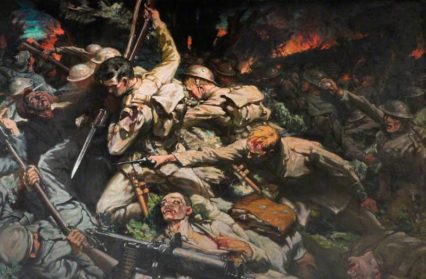

An excellent exhibition, then, although not everything in it is agreeable in terms of artistry. But perhaps, for once, that is a secondary consideration; like a retrospective that includes an artist’s less successful work, not all work in War’s Hell is great work. Most notable perhaps is the most famous. Christopher Williams’ “The Welsh Division at Mametz Wood, 1916” is an iconic theatrical vision of close-quarter combat, but is also somewhat under-nourishing, particularly in the company of some of the other works on display. Williams’ work was a commission from Lloyd George himself (Williams had already painted a stately portrait of the then prime minister), and there is something stately about the poised violence. It is in a tradition of war painting, and that tradition is for the decorating of the hallowed halls, billiard rooms and municipal gathering spots of the Britain’s Empire. Even more telling are Williams’ charcoal sketches. They are perfunctory – scenes of camps, trenches, thickets of barbed wire – but they give nothing below the surface. Muirhead Bone, a Scotsman also working on commission who passed through Mametz, sketches with an understanding of the relationship between audience and subject beyond anything Williams displays. In his charcoal work “In Mametz Wood” we are introduced to a profound loneliness, looking out with a Tommy, over his shoulder, to the exploded tree trunks and dystopic waste of No Man’s Land.

It is interesting that alongside Williams’ large imperial work are displayed various studies for the final piece, from charcoal to pencil drafts and reliefs of the images that make up the whole. Of some of the charcoal drafts, a much more startling impressionistic approach comes out. The soldiers here are faceless, their violence less defined. These studies are much more eerie, they are almost cubist in parts, and they kick back powerfully against the conservatism of the final public art.

Edward Handley-Read offers a hauntingly still vision of Mametz Wood, the debris almost part of the undergrowth, there is an unerring stillness to it that is befitting the reverence of the exhibition as a whole. This is, to an extent, about terrible violence captured in aspic. Handley-Read, who served in the Artists Rifles and Machine Gun Corps, was an English artist who painted many depictions of his war experience as well as sketching some very striking charcoal work which he would knock out at lightening pace; but it seems that it is his “Mametz Wood, 1916” that stands as his great work of that period. Perhaps it is this lack of motion that brings his work to a point, as the artist takes his time, so does the viewer.

Of what must be considered the three centre-pieces, the figurehead is Margaret Lindsay Williams’ “Wounded Soldiers at Cardiff Royal Infirmary”, another, like Christopher Williams’ Mametz painting, commissioned for a public space. It is positioned at the far end of the exhibition hall, opposite the entrance – the visitor begins with an authentic World War One stretcher, on loan from the Army Medical Services Museum in London laid out on a shin-high plinth, and ends on a ward back home in Wales, in a spirited homage to renaissance ensemble scenes. It is a painting all about comfort, about light at the end of the tunnel, and again contributes to the story whilst also being outshone by smaller, more gripping works all around it.

The focus of the visual artwork on display, inevitably, belongs to David Jones, a young artist who took a bullet in the leg at Mametz and went on to become one of Wales’ most significant twentieth century artists. The exhibition moves deftly from the work concerned with the build-up to the battle, the work concerned with the conflict itself, and then the artistic legacy of it. Jones features heavily in each section.

The selection of his sketches (including a particularly poignant sketchbook of Jones’ on loan from the Imperial War Museum, in one glass display case), taken from around 80 he made during those days in Mametz, are invaluable artistic impressions of the life of the Tommy in the trenches – perhaps all the more valuable for the lack of cameras in that particular sector. His sketch of soldiers taking Mass from a priest, vestments and military uniforms forming a stark counterbalance, is one of the most powerful 7-or-so square inches you are likely to see. Jones in this guise is the epitome of the “soldier’s voice”. His sketches speak for those otherwise lost to history. There is also on display here, amongst the various excerpts of poems from Graves, Sassoon, and Llewellyn Wynn-Griffith, the moment of connection between message, image and word, and it is spelled out most succinctly in Jones’ own words from his poem In Parenthesis: “They talked of ordinary things…”

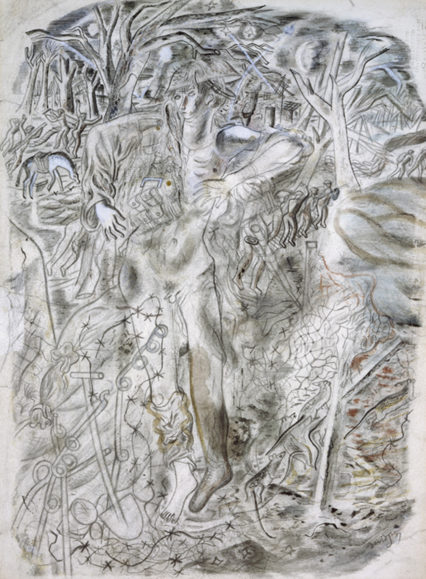

Jones takes us through the combat – his drawing “Close Quarters”, a far more involving and kinetic effort than Christopher Williams’ painting, was published in the magazine The Graphic in September 1916. But perhaps the most impressive is the inclusion of Jones’ “Jesus Mocked” from 1923. Painted directly onto the wall (it is oil on tongue and groove board, to be precise) of the Ditchling Guild workshop he was working from at the time, it is a blast of sacrilegious satire, of anti-establishment symbolism, mounted with a remarkable ability to mimic renaissance and medieval iconography. Jones is quoted as saying that something of his art never left that wood in 1916, and “Jesus Mocked” is an important testament to how the First World War helped shaped modernism and so the culture that followed. It is graffiti, but also hints at stained glass; created the same year as the publication of Ulysses, of Eliot’s Waste Land, of Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bear By Her Bachelor, Even, the year the BBC was founded, and the year the first fax was sent by telephone. If some of the work in War’s Hell is art as artifact, some of it, David Jones’ work in particular, and those “ordinary” voices he was so intent on rendering, will echo through the ages.

War’s Hell: The Battle of Mametz Wood in Art is on at the National Museum Cardiff until September 4th.

(All images used with kind permission)

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.