Gemma Pearson reviews the debut novel from Alexandra Ford, What Remains at the End.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Yugoslavia’s ethnic German population – the Danube Swabians – suffered harsh persecution under Tito’s new Partisan regime. While many fled, desperately seeking refuge in countries such as America and France, hundreds of thousands were moved to labour camps and murdered. The total number killed in the Swabian genocide is estimated at around sixty thousand. Given the atrocities carried out by the National Socialist Party in the previous years, it is perhaps unsurprising that the plight of the Danube Swabian community is frequently eclipsed. Shedding light on a cultural moment that is frequently relegated to the shadows, Alexandra Ford’s stirring debut novel examines Swabian death and displacement, the lingering effects of communal and generational trauma, and our innate desire to understand who we are and where we come from.

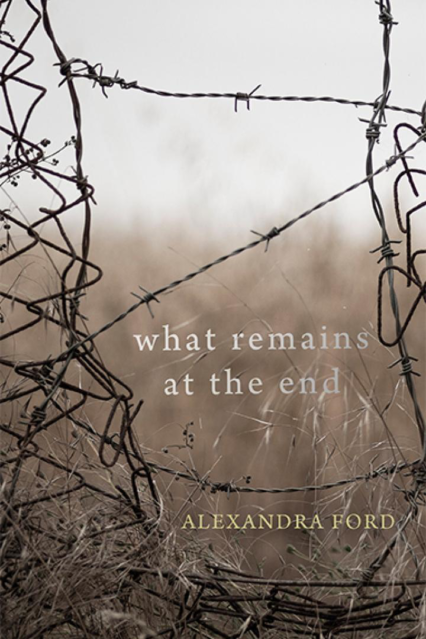

Ford’s protagonist in What Remains at the End is Marie Kohler, a modern-day American woman whose Swabian grandparents fled to New Jersey in the 1940s. Marie’s grandparents are reluctant to talk about their lives in Eastern Europe, inciting in Marie a formidable yearning for answers. When painstaking research finally presents Marie with mappable locations central to her family’s story, she travels to former Yugoslavia with David, an exciting and mysterious man who encourages and facilitates the journey of self-discovery. Driven by a desire for affinity with her ancestors, Marie vigilantly trawls the terrain of her familial history, combing deserted villages and sequestered farmlands for any hint of a familial connection. To her simultaneous dismay and relief, Marie finds several neglected memorials, overgrown cemeteries, and the long-forgotten ruins of death camps and mass, unmarked graves. While these relics offer Marie a degree of comfort, reassuring her that the lives of those lost have been in some way memorialised, their derelict states stand as ghostly reminders that the past is easily forgotten when time marches on and it no longer seems to affect us.

Ford’s protagonist in What Remains at the End is Marie Kohler, a modern-day American woman whose Swabian grandparents fled to New Jersey in the 1940s. Marie’s grandparents are reluctant to talk about their lives in Eastern Europe, inciting in Marie a formidable yearning for answers. When painstaking research finally presents Marie with mappable locations central to her family’s story, she travels to former Yugoslavia with David, an exciting and mysterious man who encourages and facilitates the journey of self-discovery. Driven by a desire for affinity with her ancestors, Marie vigilantly trawls the terrain of her familial history, combing deserted villages and sequestered farmlands for any hint of a familial connection. To her simultaneous dismay and relief, Marie finds several neglected memorials, overgrown cemeteries, and the long-forgotten ruins of death camps and mass, unmarked graves. While these relics offer Marie a degree of comfort, reassuring her that the lives of those lost have been in some way memorialised, their derelict states stand as ghostly reminders that the past is easily forgotten when time marches on and it no longer seems to affect us.

But Ford does not let us forget what did happen because, employing a timeline that alternates between Marie’s travels and Serbia in the mid 1940s, the principal narrative intersects with a series of harrowing accounts from Tito’s victims. A young boy held in a labour camp; a girl left facially disfigured following a brutal attack by invading soldiers; and a family forced out of their home and separated, are all given space to tell a side of history often misrepresented. As a result, each chapter builds on the last to create a rounded story of past and present suffering, opening up questions of recovery and inspiring readers to consider how we should begin the process of salvaging a hidden history and reclaiming concealed truths.

The overarching impression given by Ford’s confident and controlled first novel is that the history of the Swabian genocide lingers throughout generations and family lines, haunting all of those it touches with varying intensity. Having grown up with Swabian grandparents herself, What Remains at the End is a deeply personal, startlingly honest, and devastating portrayal of the lasting effects of communal and generational trauma. Perhaps the most striking element of Ford’s novel is her adept ability to convey the overwhelming, and, at times suffocating, feeling that history has a habit of living with us, following us, and seeping into every aspect of the present as we blindly move onwards not recognising its grip. Ford’s novel reminds us how the past shapes us both as individuals and as collective nations, because, to quote Ford herself, history is “something living on our shoulders.”

What Remains at the End by Alexandra Ford is available now from Seren.

You might also like…

Gemma Pearson reviews Hello Friend We Missed You, the debut novel by Richard Owain Roberts, which provides a witty and imaginative reflection on grief, loss and the importance of moving forward.

Gemma Pearson is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.