Adam Somerset attends Gideon Koppel’s film installation Borth at Aberystwyth Arts Centre, depicting a one-street seaside town.

‘What can the camera do that the eye can’t do on its own?’ The question is barked out to Gideon Koppel at the end of his introduction to the opening of his film installation Borth. His forty-minute talk, in Aberystwyth’s sleek Arts Centre cinema, has recounted the technical challenge behind his creation of a single travelling shot of the houses that back onto Borth’s beach. Koppel has glided with ease past references to Beckett, Deleuze and Heidegger, and his questioner is easily answered. ‘The camera creates a frame,’ he says, ‘and it lingers where the eye moves on.’

Britain’s coastal towns come in every contour conceivable. Borth is not alone in having a Damascus-like Street Called Straight. Ullapool, Deal, Aldeburgh all have stretches of straightness, but nowhere else is quite like Borth. It is in part the sense of being a one-street town, the shingle and wave to one side, marsh to the other. Koppel has brought the opening scene of Once Upon a Time in the West with him and shows the first few minutes. An artist sees connections, where we have seen none before. The parallel is uncanny; Sergio Leone’s scene has the same straight rail track, heading toward the distant line of mountains.

The scene is the most unhurried in modern cinema, and it is a doubly fitting parallel. The camera in Borth takes fifty minutes to record the line of houses that are Borth’s face to the sea. The term Koppel most uses is architectural bricolage. Borth is certainly the antithesis of the heritage view of an antique fishing settlement. Mike Parker is a lonely figure in writing in its praise. He likes to drink there, because its authenticity is the kind of Wales he likes. But literary visitors have been rare.

George Borrow dropped south from Machynlleth to the Ystwyth. From a train window Paul Theroux saw ‘a straggling beachfront with the shadow of the Cambrian mountains behind it.’ Jon Gower had his attention split between the abundant bird life and the rumble of Norwegian rock, forty thousand tons in all, being laid down for sea defence.

The seaward side of Borth, which is the object of Koppel’s intense scrutiny, has a divided face. Verandas and balconies have been added to the old buildings, by the score, to drink in the sunsets and sea views. Surfboard and beached boat are emblems, that the coast is a place for humankind to take its recreation. But each building sits behind a palisade of weathered former railway sleepers that is protection against the waves.

Two human beings feature in Borth. A spectral figure looks back at us from behind a French window. The Victoria Inn has its roof under repair. A man steps from a skylight, walks along the planking to inspect the roof work. A few birds flutter by. A cyclist, a Pickfords van and an Arriva bus belt past a gap in the houses. Their speed of appearance, and disappearance, emphasise the steady, inexorable roll of the camera.

Koppel’s introduction has opened with a critique of a culture that is ‘fetishised with about-ness’, overly focused on ‘capsules of the known.’ Writers and artists are routinely pushed, irrespective of liking or aptitude, onto a stage to make explication of themselves and of their work. Koppel resists explanation, preferring Borth, described simply as ‘A Picture’, to be itself.

The image that is on Aberystwyth’s gallery wall is thirty-five feet across. It has been devised to express a sense of scale via an uncommon one to two-point-eight-five height to width ratio. The day that the production team has chosen is unflattering. A fierce Southerly wind is blowing, so that washing lines, a loose drainpipe and flags flap agitatedly. The roofline drops occasionally to show a sky that is overcast. Later, a sun appears to cast some shadow, although it may be earlier. The creators have stitched the first building to the last, so that Borth has no beginning or end.

The human brain is attuned to reach its peak perception of detail while travelling at a speed of four miles an hour. Koppel’s tracking camera moves much more slowly than this walking pace, and so presents the perceiving eye with a choice. First, it can savour the rich detail of the image. A flicker behind glass may be a daytime television. Another window has a vase of flowers. A pristine holiday home, which is all garish yellow brick, stands cheek by jowl with a house of dereliction, its concrete lintels stained. A rusted cement mixer is tipped on its side like a beached turtle. A wall has the texture of carrot cake. A flag fiercely blowing in the wind is in tatters, its dragon cut back to a couple of claws.

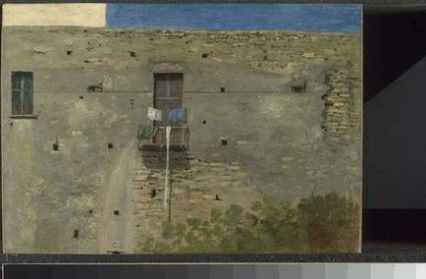

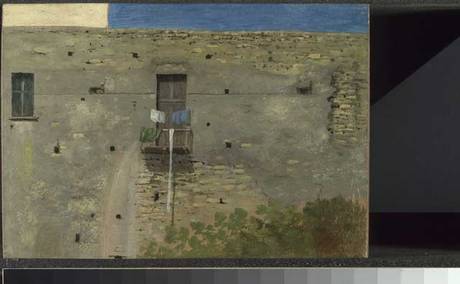

In his introduction Koppel cites Deleuze to the effect that ‘A work of art does not communicate. It does not contain information.’ Connotation is not denotation.Art’ssuggestiveness is different in kind, and greater, and never stands alone. The unfolding image of Borth has that closeness of attention that Thomas Jones brought to his Naples walls two hundred back. But the aesthetic difference is that a Jones canvas exists in space. The eye that sees it has its own autonomy of time and attention.

The eye before a film image has had that autonomy taken away and given to the maker. Borth is meditation on the difference between eye and machine. The image appears steady, but a look at the edge of the screen and the view changes. The passage of the camera is making its way, by whatever means, along a rough shingly surface. Whereas the buildings are all straight lines and right angles, the passage of the camera itself is an unsteady, halting thing. The camera makes record of its own movement, lacking the built-in mechanisms of the mind’s self-adjustment, which smooth over tremor and judder.

Borth is technologically complex. Digitisation has allowed for a single take – the storage requirement is measured in terabytes. Hitchcock in 1948 with Rope had a time restriction imposed by the physical limitation of a reel of film. But Borth also stretches technology’s resources. The Aberystwyth installation is not the full event. A second film has been designed to run in parallel showing the sea. The viewer is intended to stand between this last human settlement and the waves.

The vast image on the gallery wall is created via two cameras placed high, so there is no shadow from walking viewers. But for, all its cleverness, the central area of the image cannot achieve what two eyes do without effort, and that is continuity of focus.

Many talents have come together for Borth. Cinematography is by Oliver Curtis, music by James Bradfield, sound design by Joakim Sundstrőm. Other credits go to dirty looks, De Lane Lea and Spike Island. Film festivals are beckoning. Those who love Sleep Furiously, and they are legion, will love Borth too.

You might also like…

It’s been a year since theatres up and down the country closed their doors indefinitely. To mark the occasion, Adam Somerset reflects on the artistic vitality of live productions, and explains why digital theatre will never supplant the physical experience of live staged productions.

Adam Somerset is a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review.