Dr Emma Schofield offers a personal reflection on how far women vote rights has developed through the lens of political achievement.

On Wednesday evening I was driving from work, the same road I take most days, navigating the traffic and singing to my child who I had just picked up. I slowed down as I joined a queue near a pedestrian crossing and at that moment I saw a teenage girl, not more than about fifteen years old, running towards my car with a large plank of wood in her hands which she then flung, at point-blank range, into my car window.

I was angry. More than that, I was absolutely incensed that anyone, never mind a child, would carry out such a mindless act. In the aftermath, I spoke to the police who, in spite of their professionalism and much-appreciated empathy, couldn’t conceal a hint of weariness in their tone as I reported the incident. My experience was, apparently, just one of a number of recent events on that stretch of road, with multiple incidents involving teenagers of a similar description to the girl who attacked my car, being caught throwing stones or wood at passing cars.

Something is badly wrong when a child, of any gender or age, is stood in the dark on the roadside purposely attacking passing cars, regardless of the when, where or how. As I’ve thought back over the incident, the unsettling image of that young girl with all her energy focused on running towards my car, swinging the wood in her hands has refused to leave me.

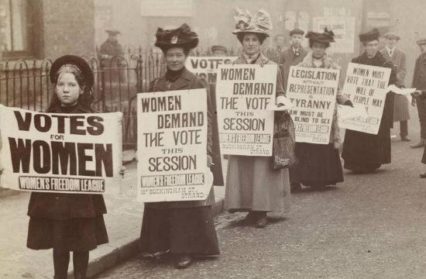

This week marks a major milestone for women and politics in the UK. On the 14th of December, 1918 women headed to the polls in a UK general election for the very first time; at least some women did. Universal suffrage was still a number of years off, meaning that only women aged over 30 who met a specific property requirement, we’re able to have their say. In real terms that meant that just one hundred years ago only two out of every five women in the UK were able to vote. To put that even further into perspective: in 1918 my four great grandmothers were young women, approaching or just entering, adult life. All four were working-class women, all had just lived through the First World War, two of them would already have been working and preparing to start families and yet none of them would have qualified to vote in 1918. Just one hundred years ago these women were still being denied their political voice and they weren’t alone. Thanks to the restrictive terms of the Representation of the People Act which had been passed in February 1918, what was a moment of victory for some, made little difference to many others. The Act ensured that over eight million women in the UK received the right to vote, but still denied that right to millions of others. Nevertheless, the significance of that moment when women were first able to enter the polling station and have their say in the country’s politics cannot be overstated.

Fast forward a century and ask people for their view of politics in the UK right now and you’ll hear a lot of words; disillusioned, disenfranchised, fed up, bored, might be among the milder responses you’d be likely to encounter. I’m acutely aware that I am considered odd by some people for the fact that since I turned eighteen I have voted in every general election, every assembly election, every council election and every referendum which has taken place. Damnit, I have even turned out to vote for my Police and Crime Commissioner. I’ve been asked countless times why I bother, why I waste my time going to mark my X on a piece of paper at every opportunity when we have a political system that is, quite clearly, badly broken. I have always given the same answer: I vote because I can, because it is my right and because it is my privilege to be able to do so. We live in a democratic nation and we should never take that for granted. I vote because I have an opinion and I’m grateful that I can express that opinion freely and because if I had been born a mere hundred years earlier, I would not have had that same opportunity.

In the grand scheme of things, a hundred years is not a long time. After all, we’ve been on this earth for some two thousand years, but for roughly one thousand, nine hundred of those years women were denied the right to exercise their political voice. Put that way, we women still have a hell of a lot to make up for. Surely by now, we should be doing more to ensure that no woman, young or old, is stood by a roadside channelling their boredom and frustration into attacking others.

We have some incredibly inspirational figures to look back on as a result of that first general election. In Wales, Professor Millicent Mackenzie had already broken boundaries having become the first female professor in Wales in 1910 when she was appointed to the role in the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire. Outside of academic life, she had co-founded the Cardiff District Women’s Suffrage Society and worked on reaching out to women in the district, before eventually standing as a Labour candidate in the General Election of December 1918, the only female candidate in Wales. In the end, Mackenzie lost out to Liberal candidate Sir Hubert Lewis in the election, but in standing as a candidate Mackenzie had joined the small number of female candidates who, in 1918 chartered new territory with their enthusiasm to represent the public.

Ambitious, curious and unperturbed by her failure to secure a seat in Parliament, Mackenzie went on to travel the world with her husband, Professor John Stuart Mackenzie, before eventually returning to her native Bristol in her later years. She was intelligent, confident and unafraid to speak up for what she believed in and, even now, that is exactly the kind of role model we should be talking about. Of course, she is not alone; there have been countless female candidates, councillors, MPs, AMs, party leaders and even Prime Ministers since that time, but without Mackenzie and the other women who voted or put themselves forward as candidates in 1918 it is unlikely that a culture of women in politics would have continued to grow within the UK.

I’m not for one moment suggesting that we should all agree with everything another woman says, I’m not advocating some kind of idyllic sisterhood where we all rush out to support political candidates simply because they are women. On the contrary, we have a responsibility to challenge and question all candidates seeking to represent us. As it does at so many other points in life, gender becomes a moot point for me when I enter a polling station and decide where to place my vote; I base my judgement solely on who I think is best able to represent me and my concerns.

What I do passionately believe, is that we can do so much more to provide a safe, secure and respectful environment in which to encourage women to take part in politics. Tragically, that is not always the case. In this milestone year for female democracy, issues surrounding the abuse and intimidation of female politicians have been painfully prevalent. Female politicians across the board have continued to report threats of violence, and even death, made against them this year. In June we commemorated two years since the murder of MP Jo Cox, while in July MPs took part in a debate about the issues surrounding the abuse and intimidation of female and male politicians in the UK. We are not alone, in October a study by the Inter-Parliamentary Union and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe revealed that over fifty per cent of women working in European parliaments had received violent threats. We must not allow our society to become normalised to the shocking reality of these facts.

I want my daughter to grow up knowing that she is free to discuss her political views, remaining respectful and mindful of others, but not afraid to speak up for what she believes in. It has taken a hundred years for us to reach this point, we cannot and must not, allow fear and intimidation to force us backwards. Earlier in the year, I argued that Wales would benefit from the creation of a team of Women’s Ambassadors to promote the needs of women in Wales and support their development, as 2018 draws to a close I repeat that call. We have a responsibility to ensure that a hundred years from now we still honour those women who first approached the ballot box or stood for government in 1918 and we have a fundamental duty to lead the next generation of women towards respectful and meaningful politics. In so doing, we secure our future and honour both the women and men, who paved the way for us to reach this point.

What might Millicent Mackenzie and her fellow female politicians and voters have said if they knew that one hundred years after their first encounter with democracy, there are a small number of young women already so disenfranchised that they are standing on the roadside mindlessly carrying out the petty crime, while the women who are fighting to improve their lives face daily abuse, threats and personal attacks? The time to act is now, we have to halt this hostile culture where political disagreement goes hand in hand with personal abuse and where antipathy threatens to consume a generation. A complacency is no longer an option, women deserve better and, as a nation, Wales must strive for more.

The author of this political piece, Dr Emma Schofield is an associate editor at Wales Arts Review.