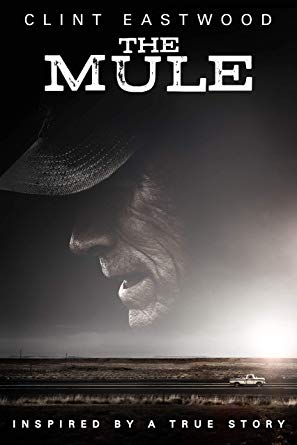

Paul Chambers considers Clint Eastwood’s latest film The Mule, reflecting on the actor and director’s legacy within the entertainment industry.

There is an inevitability that, at the age of 88, any new film made by Clint Eastwood will be seen as a farewell to the art form that has made him one of entertainment’s most iconic figures. But with his latest offering, The Mule, there is an undeniable sense of a man coming to terms with his legacy, of a person loosening the ties of the myth that has built up around him, to reveal the sensitivities and vulnerabilities of the man at the heart of it all.

The Mule is based on the true story of 90-year-old Leo Sharp, a World War Two veteran who became one of America’s most prolific drug mules, transporting thousands of pounds of cocaine across the country for the Sinaloa Drug Cartel. While this scenario is evidently potent film material, the focus very quickly departs from what, on the surface, appear to be the obvious dramatic strengths of the story, to instead explore a character dealing with the damage that a pursuit for success has ravaged on his family.

In the film, Earl’s (Eastwood) prize devotion are his flowers, for which he has received countless awards, and showcased with resounding success across 40-plus states in the country. In the opening scenes we see Earl receive yet another horticultural honour, which is followed by him buying everyone at the conference bar a drink in celebration of his success – all the while missing his daughter’s wedding.

The real story here is Eastwood’s character aiming to make amends for the decades-long neglect of his family, for the sake of his personal ambition. To begin with, Earl’s solution is throw money at the problem, paying for the free bar at his granddaughter’s wedding, and even stumping up the cash for the refurbishment of a war veterans’ bar. However, as the narrative develops, Earl comes to realise that the greatest gift he could ever have given his loved ones is his time. This is a character who is seeking to resolve a lot of wrongs, and there is, of course, an inevitable reflection of these themes on the film’s director. Earl’s estranged daughter, Iris, around which much of the dramatic tension is focused, is played by Eastwood’s real-life daughter, Alison, adding an even stronger personal resonance to this portrayal of a man walking the road to redemption.

Earl’s process of catharsis and salvation is a detriment to the emotional journeys of the other characters in the film, who often serve as little more than functional presences along his journey. There is little depth to the majority of the supporting cast, and this is no-doubt a flaw in the film. But there are also several minor scenes in which this one-dimensional functionality serves as a testament to the notion that Eastwood’s character is of a bygone era, increasingly at odds with the modern world. There are several incidences where Earl disparages at peoples’ immersion in their mobile phones; in one scene he finds himself bemused by an all-female motorcycle gang (‘Dykes on Bikes’); and he frequently bemoans the fact that he doesn’t know how to send a text message. Later in the film, however, in one of these minor scenes, Earl comes into his own. On one of his many trips across the country, he stops to help a family struggling to change a flat tyre. The husband/father, with no grasp of how to solve the problem, is struggling for mobile reception at the roadside in order to google the method. Earl simply gets on with the job at hand and gets the matter sorted practically.

The point is that this is a man of action; a Korean War veteran; a resolver of problems in a hands-on, no-nonsense fashion. In a recent interview, Eastwood declared that “we’re really a pussy generation now”, and there are more than a few instances in which he makes this point quite clearly in the film. This is a portrait of a man, the embodiment of (perhaps) an increasingly archaic set of values and principles, struggling to come to terms with what society has become.

Eastwood is man who clearly understands what he, as Clint Eastwood, brings to a film. And, much like his character in Unforgiven, there is a sense here of a stripping away of the ‘Man with No Name’ persona for which he is so well known. The difference though, is that by the end of Unforgiven, Eastwood’s character summons the old reserves and takes direct and violent action. Here, there is an element of passivity, of coming to terms with the inevitable fact that, at some point, sooner or later, he will have to hang up his guns.

Despite the easy-going tone of the first half of The Mule, there is a distinct heightening of violence as the film develops. The ferocity and the risk of this world become increasingly apparent. We know that the odds are progressively and impossibly stacked against Earl, but there is still that sense that, somehow (this being Clint Eastwood), he will find a way out. But in the story’s dramatic climax, in Earl’s final car chase, with the road blocked by a police barricade, armed officers taking aim, and a patrol helicopter hovering above his vehicle, he simply stops the car and gives himself up.

In the film’s final scene, we see Earl tending a flower in the prison garden, patting down the soil before wandering out of a long-shot, which lingers after he has left the frame and the credits begin to roll. The poignancy here, is that the running visual motif in this film is not the guns, the drugs, or the cop chases, but the daylily that Earl so highly prizes – a fragile, summer flower whose blossoms last just a day. And it is on this image that the film’s emotional focus is centred – on a single, fleeting life that must be cherished while it lasts. Despite its subject-matter, there is a gentle humility to The Mule, and this is nowhere more keenly felt than in the image of the small thing of beauty that Eastwood leaves behind in the prison yard, before taking his slow walk out of frame, at peace with himself at last.

Paul Chambers‘ is a writer and contributor to Wales Arts Review.