Wales Arts Review asked some of Wales’s top writers to pen some thoughts on the future. This new series brings together a wide variety of perspectives and ideas in a vibrant array of styles and forms, expressing hopes for a new way of doing things when the Covid-19 coronavirus is finally overcome. Political, personal, sociological, ecological, cultural – this is an evolving tableau of ideas. Here, Dai George uses his government-approved daily exercise to contemplate the potential social, political and cultural ramifications of the outbreak in Harrow (Metroland), with hopes for a more collaborative future.

I’m waiting out this strange season in Harrow, a borough in north-west London that’s become a home to me over the years. Not my original Welsh home, or the place where I pay rent, but a refuge and a waystation, centred around my partner’s family. It’s a place I’ve come to know quite well, at least a particular corridor of it that now forms the arena of my daily exercise. I’ve always loved how sorted this place seems, with its thirteen stations on the TFL network and streets of smart, functional, lightly aspirational interwar buildings, splitting the difference between Tudorbethan, art deco and whatever it is that Tesco Extras are made of. This is of course a projection as much as it is a representation, papering over drab edgelands, faded pebbledash, overcrowding and insecurity – the realities of modern life as it exists anywhere in London’s turbo-charged gig economy. Has it taken a pandemic to make this palpable? Harrow feels different at the moment, quieter and restless, though the outward architecture remains, signifying upward mobility and intergenerational calm.

An unsung railway marketeer called James Garland pulled off a PR coup in 1915 by dubbing this wider area ‘Metroland’, in a bid to entice the new, rapidly expanding homeowning classes to move here. He did a good job. Harrow is now home to 250,000 people – almost as many as live in Cardiff – and the Metroland tag has stuck, its heritage status secured by John Betjeman’s 1973 documentary of the same name. Betjeman also versified this area, in a poem titled ‘Harrow on the Hill’:

There’s a storm cloud to the westward over Kenton,

There’s a line of harbour lights at Perivale,

Is it rounding rough Pentire in a flood of sunset fire

The little fleet of trawlers under sail?

Can those boats be only roof tops

As they stream along the skyline

In a race for port and Padstow

With the gale?

The serious joke here being that, even in a landlocked nook like Harrow, the roofs stretch out like boats, connecting Metroland – metaphorically, and in spirit – to England’s watery existential borders.

Betjeman’s conservative romance no longer meets the reality of this Metroland area, if it ever did. (Clue: it didn’t.) The website Modernism in Metro-Land is one antidote, a trove of future-nostalgia celebrating the area’s cooler architectural legacies. Another is the work of Bhanu Kapil, the great contemporary poet, thinker and performance artist whose new book, How to Wash a Heart (Pavilion / Liverpool University Press), seems directly to dismantle Betjeman’s parochial vision of national and regional identity. In fact, it kicks off with the brilliant, mordant couplet, ‘It’s inky-early outside and I’m wearing my knitted scarf, like / John Betjeman, poet of the British past,’ as if to rip away anyone’s last, lingering attachments to that poet’s warm-beer-and-cricket-whites monoculturalism – or quite literally, we might say, to pinch their scarf.

Kapil’s earlier masterpiece, Ban en Banlieue (Nightboat, 2015), presented a radical reimagining of the 1979 Southall race riots in Ealing, the borough directly to the south of Harrow — Metroland — that’s been home to a large South Asian community since the decades following the Second World War. Her work reminds me, if I needed reminding, that Britain’s postwar history is one of widespread exclusion as well as partial, always-conditional inclusion, and that every multicultural success has been won at significant, sometimes violent cost. Like Southall, Harrow’s population has been fundamentally shaped by diaspora from the former British Empire, with many families – including my partner’s mum’s – leaving India and settling here in the years following Partition. (The borough had an almost even split between its white and Asian/Asian-British populations at the time of the 2011 census, 42% in both categories.) Harrow was also one of the early epicentres for the pandemic, with the local Northwick Park hospital being turned quickly into a hub for treating Covid-19. Knowing what we know now about how this virus disproportionately attacks and bereaves people of colour, one can’t help thinking that this feels more like an injustice than bad luck.

Kapil describes the voice of How to Wash a Heart as that of ‘an immigrant guest in the home of their citizen host’, and the wider collection is intricately, painstakingly involved in the question of hospitality – how communities offer welcome, or deny it, and how nation states might fortify or dissolve those categories of immigrant and citizen, guest and host. That imagery should be haunting us at the moment, as politicians debate migrant people’s right to live and work in this country, threatening them with abstract point systems one minute and scrambling to sanctify their frontline efforts the next. Shameless, and thoroughly shaming. For a decade now, I’ve known great, unconditional hospitality in Harrow, finding myself welcomed into family lunches, celebrations and funerals in Metroland, and more often than that being simply welcomed – allowed to loaf around reading the paper or asked to pitch in with chores, with no expectation that I prove myself beyond that.

Why is any of this relevant to Covid-19? Partly, it’s just that How to Wash a Heart addresses the world of lockdown with uncanny prescience, capturing its fragmented texture and vectors of distraction, and the constant intersection it reveals between personal and political precarity. But I’m also imagining our uncertain future, unavoidably, through the lens of Metroland: a particular place, an embodied reality. Whatever settlement emerges on the other side of lockdown – and I think most of us, thank god, understand that it must be fairer and more sustainable at every level – it will have to negotiate with communities and ways of life that exist here, now.

My daily walk starts in a space where, unashamedly, I would like to see the clock turned back, to the time immediately before lockdown came into force. Harrow Recreation Ground is a park little different from many across Britain, about a mile in parameter, its pathways circling and bisecting an interior filled with basketball and tennis courts, pavilions and bowling greens, football pitches, crickets nets, rewilding areas – and fields. Glorious square feet of open, uncircumscribed grass, where in normal times people would be free to laze and read and canoodle, without fear of caution from a passing police officer. To be fair, I’m not sure that the hardened minority who continue to use the park for these purposes do so with any fear – the fearful would be too timid, by definition – but I resent how our solidarity has been undermined by epidemiology and public policy. I don’t want to give a damn about whether you lie back in the sun and smoke a joint or not. The sooner that parks can get back to being a ramshackle, libertarian frontier where (almost) anything goes, the better.

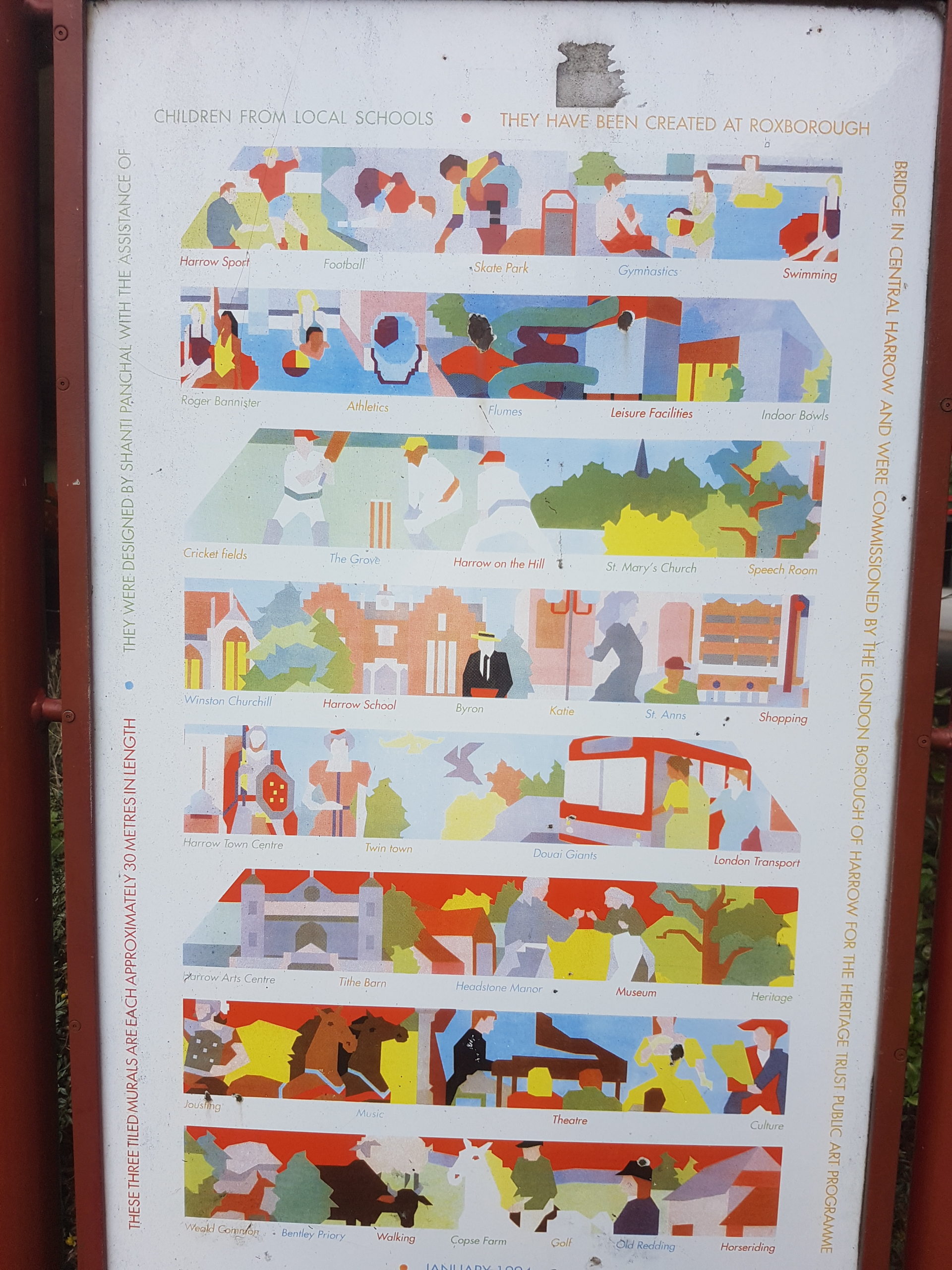

Leaving the park at its south-east corner and turning right, I come in about three minutes to one of my favourite places in Harrow – or, really, in the world. At the bottom of Roxborough Road a set of murals occupies three sides of an underpass, metres away from the entrance to a Morrisons megastore. A busy roundabout roars overhead, making it difficult to relax and enjoy the scene, but whenever I pass through I try to take a moment to appreciate it. Here’s a board that captures the murals in overview.

I love the civic optimism of these transhistorical, primary-coloured tableaus. Yes, there’s a nod to Metroland’s venerable boy’s school, a bastion of privilege less than a mile away up the Hill, but we can forgive it that (a condition, I would guess, of the local government commission, back in the day). What stands out are the panels depicting contemporary life at the time the murals were made in 1994: scenes of local boys and girls at their leisure, in swimming pools and skate parks; adults hopping on the bus to work or to the shops, a woman in a sari stepping on first. These may seem like small windows onto limited horizons, too modest to be held up as any sort of model for change. I admit I have to stop myself from romanticising them, by turning them into a happy, post-imperial version of Betjeman’s Metroland arcadia – yet equally I want to stand up and affirm their real power, and intentionality. This isn’t, after all, a transparent item of municipal decoration, but an artwork made by Shanti Panchal with the help of local schoolchildren. It is inherently value-laden, though it specifically does not make any argument for multiculturalism. It understands that the lives of local citizens aren’t on the table for argument, and are in any case too various for that problematic label ‘multiculturalism’ to encompass. Instead of argument, it simply asserts the reality of those lives, and the reality of their proximity and dependence, through the spatial interaction of black, white and brown bodies on the tiles.

From the Roxborough murals, my walk takes me under further bypasses, past high-rise commuter flats and billboards advertising mobile minutes and remittance services to Ghana and Sri Lanka. I struggle to imagine how the post-Covid future will be much less globalised than the present, and I’m inherently suspicious of any environmental argument that seeks simplistically to reverse these distances in the name of sustainability. I worry about the types of nativism that might be lurking, posing as localism, in the philosophies of the left. But I worry most of all about the crude, unapologetic racism that might erupt among a cultural right at once emboldened by Brexit and chastened by the social and economic costs of the pandemic. That paradox could turn lethal over the coming years, and must be exposed and resisted at every opportunity.

The last leg of the walk in Metroland before I turn back home takes me up a steep physical and social gradient to the boy’s school on the Hill. Here’s where I legitimately get to call it exercise, and where the debate about the near future grows murkier. The left will have bigger fish to fry than abolishing private education once the pandemic is over, but one can’t deny the ghostly, vacant stillness of the school grounds at present – how they feel emblematic of a luxury that shouldn’t be indulged anymore. Sometimes my partner and I take this walk together, and in a slightly delirious mood we stop and laugh at the furloughed school shop, its windows still filled with branded water bottles, board games, boater hats and yearbooks, about as far away from an essential service as you could imagine. (We wonder whether they’ll have to start selling baked beans and milk to reopen.) Especially ridiculous is a set of matching teddy bears, a little one cwtched up in the big one’s lap. It’s rarely a good idea to share private jokes, much less to explain them, but we’ve taken to calling the baby one Teddy Benn, after his privately educated almost-namesake of Labour Party lore, and we’ve pledged to buy him when all this is over and raffle him off for socialist causes.

When this is over: who knows when that will be? If you penetrate further into the leafy streets of the Hill, you’ll find a blue plaque to one of its former residents, the Victorian ‘poet, critic and educationalist’ Matthew Arnold, who for five years lived in a house named after another poet, the Old Harrovian Lord Byron. Byron, Arnold, Betjeman: the great white males stretch in a neat but slowly dwindling line, bringing to mind the ‘melancholy, long, withdrawing roar’ of the godless sea in Arnold’s great poem ‘Dover Beach’. I hear that disorienting roar in the sudden contraction of a society, and economy, that was already built on the flimsiest banks of sand. We shouldn’t underestimate the pain that will accompany our transition to something different, even if different, eventually, equals better. Nevertheless, I hold out hope, at least, that the cultural and artistic response to this crisis will be polyvalent and collaborative. Rather like the Zoom interface that we’re all growing so intimately familiar with; in other words, less like Arnold’s solitary cry into the void, and more like the work of Bhanu Kapil.

You might also like…

Carolyn Percy reviews Harrow Lake, Kat Ellis’ darkly nostalgic thriller, sure to leave you asking for more.

Dai George is a Welsh poet, novelist and critic. His first novel, The Counterplot, has just been published as an Audible Original. The Claims Office, a book of poems, is published by Seren.