Ben Woolhead was at the Cardiff School of Journalism and Media for the final public event in the long career of one of Wales’ most iconic Magnum Photography photographers, David Hurn.

Organisers The Royal Photographic Society, Magnum Photography and National Museum Wales have given today’s event – allegedly its star’s last public speaking engagement – the appropriately grand title “Key Decisions of Magnum Photographer David Hurn”. Hurn’s own edited version, emblazoned across his first slide, is wryly self-deprecating but also characteristic of someone with a pronounced preference for reality above artifice and pretension: “Key Moments in 64 Years of Averting Malnutrition”.

The loose lecture format affords Hurn generous license to talk at length about his illustrious career. Many of the incidents may be well-rehearsed, but he is a storyteller in person as well as in pictures, and when he talks, you certainly listen.

Hurn begins by pinpointing the single most significant event in his life: catching sight of a Henri Cartier-Bresson photo in an issue of Picture Post while sat in the officers’ mess at Sandhurst on 12th February 1955. The image was of a Russian man buying his wife a hat; Hurn, whose first memory of his father after he returned from the Second World War was of accompanying his parents on an identical shopping trip in Cardiff, broke down in tears. By the time he had recovered himself and marvelled at the extraordinary emotional impact that even an apparently innocuous photo can have, he knew for certain what it was that he wanted – or indeed had – to do.

It was that epiphany that prompted him to hitchhike to Austria with his friend John Antrobus (later a writer on Spike Milligan’s The Goon Show) the following year, and then to sneak across the border into Hungary in the back of a Red Cross ambulance with the aim of photographing the Revolution. No sooner had they arrived in Budapest than he met a journalist from Life, who, upon seeing his camera, immediately commissioned him to work for the famed American weekly magazine. Little did they know, Hurn laughs, that he was still regularly consulting his beginners’ guide up in his hotel bedroom, unsure of how to load new rolls of film into his Leica. He openly acknowledges his good fortune at “starting at the top” – but the fact that he has managed to “cling on” ever since is a testament more to tenacity, dedication and hard work than to luck.

Nevertheless, another fortuitous encounter took place in Trafalgar Square, where he was approached by a fellow photographer while taking pictures of the pigeons. The other man turned out to be Sergio Larrain, a Magnum member who had recognised in Hurn the absolute concentration of the talented photographer. Reassured by Larrain that his pictures of every day and the apparently trivial were his best, the novice had the confidence to follow that path – one that at the time was less trodden, but that soon became profitable as the number of colour supplements increased. Over the course of today’s address, Hurn talks time and time again about the importance of discovering your own distinctive voice as a photographer; Larrain was clearly instrumental in his own decision to focus on “tinsel society”, to borrow Don McCullin’s term – on the minutiae of life and on human interaction and emotion.

Hurn saw his contemporaries McCullin, Ian Berry, Philip Jones Griffiths and John Bulmer not as rivals but as sounding boards and sources of inspiration, and has throughout his career learned invaluable lessons from the best in the business. Volunteering as an assistant to workaholic Bruce Davidson when he was visiting the UK taught Hurn how to think in terms of series rather than solo shots and how to be patient and persevere – as well as the importance of having a sturdy pair of shoes. Elliott Erwitt convinced him not to turn his nose up at commercial advertising commissions, on the grounds that they might present useful learning opportunities and the fees earned could be used to bankroll other personal projects. From Eve Arnold and her candid shots of Marilyn Monroe, he says, he came to understand the value of trust and intimacy between photographer and subject, while Diane Arbus impressed on him the frequent difficulty of gaining access to subjects in the first place.

Fortunately for Hurn, he found himself moving in the same circles as people who could open doors. Peter O’Toole, Michael Foot and Ken Russell were all regulars in the coffee shops that he frequented, and the doors that they and others were able to open led to work behind the scenes on the sets of the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night, four different Bond films and Barbarella, starring a young Jane Fonda. (Fonda remains a firm friend. Only two days previously, he says with a smile, she emailed to say that as a woman the way to get media attention at the Oscars isn’t to wear a striking new dress but one that you’ve worn in public before.) These days, most of his income comes from the sale of prints, and the photos from this period are inevitably the most popular.

If Hurn became wrapped up in the fashion, culture and “tinsel society” of the Swinging Sixties, then the Aberfan disaster of 1966 jolted him out of it. Acutely aware of the apparent insensitivity of taking pictures when you know people don’t want you to be there, he nevertheless continued to shoot, convinced that documentary evidence of the horrors would be vital in ensuring that such an avoidable tragedy never happened again.

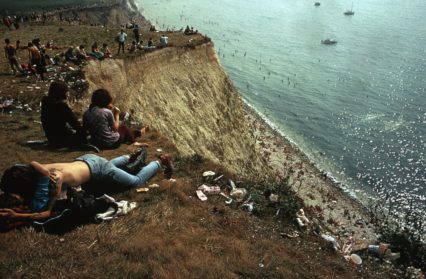

The disaster brought him back to Wales both literally and metaphorically. By 1970, he had left London behind and was once again living in the country of his youth, and over the past five decades, he has spent much of his time traversing the nation in photographic pursuit of its culture and people, with Raymond Williams as his spiritual guide. His findings have been presented in two books, Land of My Father (2000) and Living in Wales (2003) – the latter of which many members of the audience are now clutching signed copies.

In light of his own dictum that you should try to learn from the best, what words of advice does he have for us? Be a doer, not a talker. Don’t whine about problems, seek out solutions. Learn by looking at lots and lots of pictures. Practise, practise, practise. Be self-critical. Get inspiration by flicking through magazines. Always take pictures as though you’re shooting a story. Don’t obsess over equipment (a camera, he’s fond of saying, is only “a box with a hole in the front of it” and digital cameras are, if anything, “too sharp”). Don’t get hung up on technique, either – that can be easily taught. Much more important is a passion for photography and your preferred subject matter – even if that subject matter is “police kicking kids” (which is what got Tish Murtha accepted onto Hurn’s legendary documentary photography course at Newport).

Asked about his membership of Magnum Photography, Hurn expresses pride at having received the recognition of his peers and praises the agency for its continued adherence to “old-fashioned values” and rejection of eminent photographers whose behaviour is rude or arrogant (naming no names). For his part, Hurn is instinctively wary of those who call themselves “artists”, suspecting that in most cases it’s a way of claiming superiority over others who don’t: wedding photographers, for instance, whose work is often people’s most prized possession – or radiographers. An allusion to his colon cancer diagnosis in 2002 raises the biggest laugh of the afternoon: “The most important picture in my life was taken up my backside.”

As Hurn has said previously, all photography improves with age. Sadly, all photographers do not. A light-hearted question about his project of revisiting Mediterranean resorts that he first shot before the tourism boom – “Do you need an assistant for your trip to the south of France?” – elicits the surprisingly poignant and candid response that he’s now physically incapable of working for more than three and a half hours a day and finds himself struggling with loneliness when without a companion. He is now taking more pictures of the landscape “because it doesn’t move and you can go back and take it again” and starting to shoot in his home village, Tintern, because he doesn’t have to travel far and it’s on the flat. This lifelong doer is clearly frustrated at finding he can do less and less; perhaps his insistence that this is his last speaking event is because he doesn’t want to become merely a talker.

Hurn’s final slide is a photo he took of his father waving cheerily from his chair in a care home; by the time Hurn had got home from the visit, his dad was dead. He has brought us full circle, back to the emotional and intensely personal power of an image. Larkin famously claimed, “What will survive of us is love”. What survived Hurn’s father is love and that picture – and what will survive of Hurn himself is a fierce love for photography and a remarkable body of work.

To see the photography work of David Hurn, go to the Magnum Photography website.

Ben Woolhead is an avid contributor to Wales Arts Review.