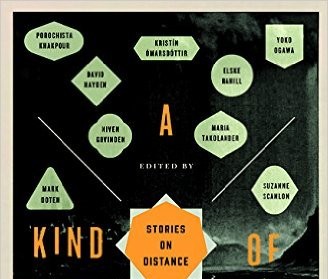

Zoe Ranson casts a critical eye over A Kind of Compass, a short story collection edited by Belinda McKeon.

In Belinda McKeon’s introduction to A Kind of Compass, she raises the idea that short stories are not darling, but daring. This sets the tone for the collection of them that follows. Spanning decades and continents, they take you from the relative safety of the place of reading to one of discomfort. The subtitle is essential. Distance works as a truly universal theme, one that resonates through disparate protagonists, from Kevin Barry’s Spanish loner locked into a gruelling hand-to-mouth existence, to the Astronaut in Maria Takolander’s ‘Transition’, trying to find her way back home.

Space travel is a British preoccupation this winter, from the imminent flight of British astronaut Tim Peake to the ‘Geeks will inherit the earth’ mania streaking through the movie-going public eagerly anticipating ‘The Force Awakens’ – versions of outer space as different to one another in the stories which open and close this anthology. The stories mirror one another, concerned with the earliest preparation for space travel and its reverse – an astronaut lost in space trying to find her way home. Beginning and ending with purported and actual space travel – something we can’t fully understand – lends the anthology a skewed symmetry and is an accurate representation of what it bookends.

Many of the stories reveal themselves gradually. The openings are ambiguous, clouded with possibility and demand the reader to immerse themselves in the language and consider the connections of images. The opening story, ‘Terraforming’ unfurls with a sense of something unsettling, the reader must decipher what situation they are exploring incrementally. The words are precise and accurate, like this sliver of life, an overnight stay in London with a sister:

They shopped for clothes and Boots Cosmetics, saw a musical, ate chocolate cereal in their hotel room and talked a lot in a way they hadn’t done since. But there are also images which sound good, but say nothing: ‘dark veins of the underground’.

A number of stories take flight in other ways. The aeroplanes in the opening pair of stories show very different scenarios linked by the familiar ritual of preparing for take-off. Common to these stories too is the experience of the protagonist’s ability to deal with strangers – encounters up-close and personal with characters who challenge them. In Sam Lipsyte’s ‘The Naturals’, a surreal tale of familial woe, the show is stolen by Sam’s co-passenger, Pro Wrestler/storyteller, the Rough Beast of Bethlehem.

The gulf between cultures, ages, and languages is skilfully explored in ‘Six Glorious Days in Vienna’ which sees a Twenty year-old on a package tour become unwittingly caught up with a roommate triple her age. The young protagonist’s plans of exploring the city romantically fold as she accompanies the older woman to the nursing home each day to keep vigil at the wrong patient’s bedside.

The centrepiece of the collection is a back-to-back double bill of heartbreak. Kevin Barry’s ‘Extremadura (until Night Falls)’ and ‘Holy Island’ by Ross Raisin are stories yoked with the same undeniable ache that call you to once more reassess what you have, with life-affirming brilliance.

Clearest of them all is Sara Baume’s ‘Finishing Lines’ – ostensibly a quest to ‘stop the pigeon’ framing a subtle exploration of post-natal depression. It is calm and measured and the story unfurls without condemnation or suggesting that it can’t really be possible to want to get away from your baby who caused you such physical pain.

In her essay, ‘Fail Better’, Zadie Smith asserts ‘reading, done properly, is every bit as tough as writing’, and other stories contained here are more difficult to read for either meaning or message, and proved particularly tricky to decipher what lies at their heart. ‘The Rape Essay or Mutilated Pages’ drew to mind the oddness of Eleanor Catton’s intriguing, tricksy novel The Rehearsal and Zoe Pilger’s 2014 book Eat my Heart Out but ultimately confused me.

Distant Song is a fable with the killer last line: ‘Their lives plummet in value’.

‘The Unintended’ by Gina Apostol works as homage and pastiche of the fascinating french writer Georges Perec. Apostol reflects the structure of a piece from Perec’s collection Pigeon Reader, where sections of the tale arranged out of sequence are denoted by letters of the alphabet (here the timeslips are numbered rather than lettered).

The classical idea of making the strange familiar and the familiar strange appears at first glance to form a backbone, but on deeper exploration the strange in this collection is rarely rendered familiar. Even cities that could be recognisable are made not so. There are other challenges – linguistic, referential and psychological – which pose existential questions. What do you know? Who do you think you are? You aren’t lead, you are expected to work, the difference between an administrated-to-the-letter excursion and a Bear Grylls survival challenge.

McKeon also says in her introduction, ‘A good story takes its readers to places they didn’t particularly want to go’. And it’s true you can be disrupted – but not necessarily – for a story to be good, it doesn’t have to unnerve you or derail through bewilderment. The most interesting and engaging stories here are tinged with strangeness but don’t lose you completely.

In any anthology of work by different writers, there are close-ups and longshots. A journey, a measurement – time passed. If you are looking for a challenge, and are willing to go the distance, you might find something you didn’t know you were missing capsuled here. There are secrets, shattered expectations, misunderstandings and double lives shrugged up to the surface so their duality can no longer remain truly private. At their most solid they go the distance there and back again, no-one remains in stasis. A book to take with you on your own journey. To dive into, get lost in for a while, before you emerge at your destination, clawing at normalcy, gasping for air.

A Kind of Compass by Belinda McKeon is available from Tramp Press.

Zoe Ranson is a writer, actor and contributor to Wales Arts Review.