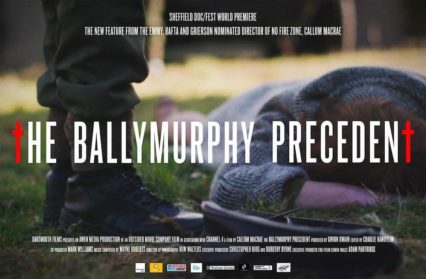

The Ballymurphy Precedent, A Channel 4 documentary made by Ffilm Cymru Wales offers a new take on one of the most notorious episodes of ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland. Angela Graham considers its relevance for a Welsh audience.

Vicky Cosstick, in her piece for current affairs platform Northern Slant on The Ballymurphy Precedent, rightly takes issue with a version of the film’s publicity which calls the 1971 deaths of 11 civilians in Belfast an ‘unknown story’. When I read that phrase I wondered indignantly ‘unknown to whom’? For whose benefit is this film made, I thought? But I ‘caught myself on’ as they say in my home town of Belfast and did a bit of checking. The production’s facebook page and website refers, with more accuracy and less salesmanship, to a story ‘that few have heard of’.

Why does this distinction matter? Because it goes to the heart of one of the major issues The Ballymurphy Precedent raises: the management of information, and specifically the advantage that a state has over individual citizens in this respect. And it highlights the chronic under-reporting of Northern Irish affairs in the UK as a whole.

A story depends on who’s telling it and to whom, and on who controls the medium. The relatives of those who were killed were, the film makes clear, severely disadvantaged in this respect. And this was despite the fact that no one who was living in Belfast in August 1971, as I was myself, could have failed to know about these awful deaths. They occurred during the first three days of the imposition of internment without trial.

There should be little surprise that these 11 killings did not attract the notoriety of the 13 Bloody Sunday killings that happened in Derry in January 1972. The Bloody Sunday deaths happened within a twenty-minute period, during, or in the vicinity of, an organised event which the media were covering. The deaths in Ballymurphy occurred over several days, at several sites and the victims were not engaged in a common endeavour. Bloody Sunday was on our television screens promptly, the journalists’ own shock conveying itself unforgettably. The Ballymurphy deaths are known only from witness accounts and army statements.

The relative powerlessness of the victims and their families is powerfully but subtly exemplified by the length of time it took for them even to meet one another. Tellingly, the catalyst for this was a Forgotten Victims event a few years ago. Dealing with the legacy of the Troubles is proving challenging and controversial but initiatives designed to break isolation and silencing are increasingly sophisticated. The dynamic result of the families’ encounters with one another is simply and effectively demonstrated in the documentary.

The ‘precedent ‘of the title refers to the film’s theory that the failure (or refusal) of government and army to learn lessons from the Ballymurphy situation led to the debacle in Derry five months later. If… If only… echo throughout.

The film is more than an account of tragic events. It exemplifies the continuing struggle to come to terms with the effects of the Troubles. One of the bitterest of those can be the feeling that one’s pain is not recognised; it results in nothing and changes nothing and that, in some strange hierarchy of suffering, it has been relegated to the bottom.

A screening on Channel 4 is due in September. The 10thof that month sees the closure of the Northern Ireland Government’s Public Consultation on Addressing Northern Ireland’s Past This has been running since May.

Judith Thompson, the Commissioner for Victims and Survivors, has complained that, “the lack of a high profile public information campaign could result in thousands of victims and survivors in Northern Ireland missing out on the opportunity to have a say on the institutions designed to give them access to justice, information and services.”

And this is 47 years after the Ballymurphy killings.

In a hard-hitting statement on 26thJuly, she goes on to claim that “our locally elected representatives have been virtually silent on the need for individual victims and survivors who are not involved in groups to be given the information and encouragement to have a say in how an Historical Investigations Unit, an Independent Commission for Information Retrieval, an Implementation and Reconciliation Group, and an Oral History Archive could be developed to benefit those who have suffered the most.”

Note that term “survivors who are not in groups”. This would have applied to the relatives of the Ballymurphy victims and is very significant, referring as it does, to those who have not, for whatever reason, benefitted from the support of others.

I’ve spent most of the last 9 months in Northern Ireland researching a novel set there between 2015 and 2017. I was struck by two contrasting attitudes to the Troubles. One was, “Hope your novel’s not about the Troubles. We don’t want to hear any more about them. They’re in the past. They hold us back. Everything’s different now.”

The other position was contradictory, asserting that only by thorough reflection and engagement with the past can people live adequately in the present and create a future worth having.

So the first task I gave myself was to investigate both standpoints. I’ve come to the conclusion that I disagree with the it’s-all-behind-us one.

One of the things that swayed me was the multiplicity of evidence presented at a conference in February on the Transgenerational Transmission of Trauma. I recommend David Bolton’s Conflict, Peace and Mental Health: addressing the consequences of conflict and trauma in Northern Ireland if you need convincing that it is not only those who have been injured or bereaved who are paying a price for the violence.

But why should this particular story matter to audiences who have never experienced militarisation? Because violence is still touted as a legitimate means of advancing civilisation and the rule of law – witness the British government’s willingness to countenance the death penalty for alleged jihadists under American jurisdiction; and because a government can still demonise and dis-respect groups with little societal heft, such as the Windrush Generation.

And because a large part of the United Kingdom is without a functioning government. Those shootings on that housing estate in Ballymurphy were an extraordinary irruption of extreme violence into a suburban setting but they, and others like them, became normalised. Can we imagine England with no parliament? Wales with no assembly?

As to why a Welsh audience should be interested in the story of these deaths, I hope to find out when I chair BAFTA Cymru’s post-screening Q & A with Director, Callum Macrae at Chapter Arts Centre, Cardiff on 8thAugust. The documentary has been made under the auspices of Ffilm Cymru (the film agency for Wales) with a lot of input from Welsh crew.

I’ve lived in Wales for 36 years. The Welsh, I’m going to boldly generalise, foster an affinity with Ireland. In the 80s and 90s a qualified admiration for the apparent effectiveness of the Irish − especially the Northern Irish − willingness to go to political extremes resulted in a slew of dramas about insurrectionary politics that I venture would never have been commissioned in England or Scotland. Welsh playwrights and screenwriters were drawn to working out their attitudes to the fact that violence seemed to purchase political leverage.

The development of devolutionary politics has, thankfully, meant that few Welsh citizens have lost their lives in the pursuit of democratic rights. But the effort to create a political system sensitive to the needs on the ground and serviced by media which are capable of representing the people of Wales in every forum is a huge challenge.

Ultimately The Ballymurphy Precedent is a film not only about Northern Ireland but about the British state and how the centre of power is repeatedly tempted to discount those at the periphery. Wales is a country on that periphery and has its own stories to tell − if it can avoid pulling punches.

Technically The Ballymurphy Precedent is a very assured documentary, with first-rate camerawork and editing, and with an admirable sense of restraint in the handling of the appalling detail of the deaths. The use of a bird’s-eye view in the reconstructions of the shootings results in clear presentations of the facts as asserted by the victims’ families while avoiding gratuitous elements. Dignity is maintained.

The sense of filmic structure throughout is exemplary. It is a long film, paced as well as it could be, given the director’s choice to lay out a scene-setting account of the background to the Troubles (nearly 30 minutes); the numerous contributors and the unhurried rhythm.

With any documentary it is legitimate to ask whether any relevant voices are not heard. It might be claimed that Callum Macrae makes little room for a unionist take on the origins of the Troubles but, against that, his choice of a soundbite from then Prime Minister, Brian Faulkner is undeniably accurate. Faulkner is shown blaming the IRA more than the insupportable social injustices that gave that organisation its entrée. It is therefore significant that the historian who gives the factual context is not from a nationalist background.

Macrae’s standpoint is close to that of the victims’ relatives and only at one point does he challenge anything that they offer. The film makes a very good case for accepting that their position is unassailable. In fact, it exemplifies considerate un-sensationalism to such a degree that a film by him on a Northern Irish subject from a unionist perspective would be a fascinating prospect.

At the end of The Ballymurphy Precedent, one of the victim’s relatives makes a humane and large-spirited assertion about the republic of pain in which all those who suffer the effects of violence are citizens, whether soldier or civilian. “We’re all suffering the same thing. So the Truth needs to be told. That’s the only way you can draw a line under the past – tell the Truth,” she says.

Angela Graham is a writer and documentary-maker. Her short story ‘The Road’, set in East Belfast in 1969 and 1971, appears in the current edition of the New Welsh Reader.

You might also like…

As arguments continue over the future of the British border with Ireland, Angela Graham examines the role of poetry in Troubles: The Life After, on BBC2.

Angela Graham is a contributor to Wales Arts Review.