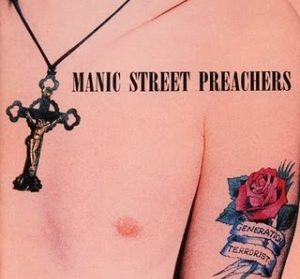

As Manic Street Preachers’ debut album Generation Terrorists reaches the ripe old age of 25 we plunder the Wales Arts Review archive to revisit Craig Austin’s take on its distinctive cultural impact, an article that originally formed part of our Classic Welsh Albums series.

“If you built a museum to represent Blackwood all you could put in it would be rubble and shit”

In 1991, the notion of Cymru being in any way ‘cool’ seemed as likely as the Welsh rugby team ever achieving another Grand Slam; the denigration of the band’s hometown by Richey Edwards, the Manic Street Preachers’ part-time guitarist and full-time Minister of Information, being suitably emblematic of the nation’s fragmented declining self-image and its (then) lowly status within the wider United Kingdom.

The flag-waving national pride demonstrated by the band in its later incarnation would have been anathema to the four wide-eyed media pariahs in stencilled nylon blouses and skin-tight white Levis who detonated like a car bomb onto the alternative/indie scene of that year. Yet James Brown, founding editor of Loaded, then of NME, and an early champion of the band, was nevertheless convinced that the fact that they hailed from Wales incited them from the outset: “In the early 90s the Welsh were well on their way to becoming the new Pakistanis or the new Irish. It was quite prevalent, I think it probably started with bashing Neil Kinnock, it’d become very common to just slag the Welsh off and I’m sure that probably built up their sense of alienation. They came from Blackwood, where’s Blackwood?”

To a tiny cabal of early acolytes who bought wholesale into the band’s erratic scattergun philosophy of glitter, spray-paint and Marxist polemic the irresistibly magnetic pull of the Manic Street Preachers was a dazzling shaft of light in the prevailing pop cultural fog of drab conformity and seemingly perpetual under-achievement. Yet to many in the music press, and in particular their older more joyless peers, they were nothing more that a bunch of jumped-up mouthy kids, infamously “doing The Clash in a school play”; a fleeting industry in-joke and proof positive that the practically non-existent Welsh music scene was never going to get any bigger than The Darling Buds.

A convenient focus of universal derision at first, not least in their homeland where initially the ridicule was at its most acute – the band notably resisted playing any significant Welsh dates until a Cardiff University show on the Generation Terrorists tour – by the end of 1991, despite (and possibly, because of) signing a lucrative multi-album deal with Sony, the Manic Street Preachers were without doubt the most hated band in Britain.

“The Manics talked lipstick and they talked Lenin, they talked Marilyn and they talked Marx, and they threw it all together and understood that rather than just droning on about the politics, it was the combination of the politics with the iconography that made it exciting. They were full of hate and desire”

When Generation Terrorists was released in early 1992 it confused and confounded, as the band had no doubt hoped that it would, but possibly not in the way that they’d initially intended. The much-touted aim to sell 16 million copies of this, their debut album (a double album, no less) and then split up in a blaze of wanton self-destructive glory convinced no-one, least of all the band themselves, of the true nature of their master-plan of cultural entryism.

When Generation Terrorists was released in early 1992 it confused and confounded, as the band had no doubt hoped that it would, but possibly not in the way that they’d initially intended. The much-touted aim to sell 16 million copies of this, their debut album (a double album, no less) and then split up in a blaze of wanton self-destructive glory convinced no-one, least of all the band themselves, of the true nature of their master-plan of cultural entryism.

Yet to those who had only ever viewed the band as nihilistic punk rock outlaws the slick big-budget transformation of the intense syntax-mangling songs that had previously only been heard on the tinny in-house sound systems of the likes of the Bristol Fleece and Firkin seemed a world away from the breathless heart-bursting rage of their initial Heavenly singles. Though, with hindsight, the band now regrets the thick layers of industrial major label polish that was liberally applied to its raw material, it was very much in keeping with the colossal, unapologetic ambition they espoused as part of their calculated ‘year zero’ bedroom manifesto; itself a confrontational rejection of what they felt to be the meek and dreary aimlessness exemplified by much of the British indie scene.

The very fact that the embryonic Manics opted to align themselves with the commercial enormity of Guns ’n’ Roses and Public Enemy rather than the anaemic crusty/baggy axis of 1991 was a knowingly confrontational act at the time; America, and black America in particular, being the longstanding nemeses of the UK’s white, provincial indie scene of that period.

The band’s other improbable goal, to get ‘Repeat’ and its recurring radio-unfriendly refrain of ‘Repeat after me! / Fuck queen and country!’ to the top of the charts stalled at number 26 though its ‘Stars and Stripes’ album remix by The Bomb Squad at least succeeded in making a tangible link between the band and the broader Public Enemy church that they so devoutly worshipped at.

Like many debut albums its undoubted high-points (and in Little Baby Nothing and Stay Beautiful those highs are sporadically giddy) are inadvertently diluted by the band’s determination to fatten it up with pretty much everything they’d written up to that point, “to say everything we had to say”.

It’s one of the less obviously sloganeering inclusions that most plainly benefits from the major label ‘big bucks’ makeover though; one that showcased the real artistic potential of the band and which for many redefined the perception of the Manics as something other than a comedy Welsh punk band.

It’s one of the less obviously sloganeering inclusions that most plainly benefits from the major label ‘big bucks’ makeover though; one that showcased the real artistic potential of the band and which for many redefined the perception of the Manics as something other than a comedy Welsh punk band.

Motorcycle Emptiness, a game-changing studio construct fused from embryonic songs written on a bunk-bed in the bedroom that James Dean Bradfield often shared with his cousin Sean Moore, was initially going to be held back for the band’s second album (proof, if proof were needed, that the ‘one album apocalypse’ was always a commercial non-starter) on the basis that it was thought to be ‘unrepresentative’ of the nascent Manics and a jarring quantum leap in their musical capabilities.

Its accessible commercial veneer led by a timelessly killer guitar hook masks a fatalistic treatise on alienation, resignation and despair that had not been so magnificently broached since the earliest days of The Smiths. This populist Trojan horse was, for many, their initiation into the steadily growing cult of the band and coupled with a quote-laden gatefold sleeve that in its promotion of Larkin, Pollock and Henry Miller read like a suggested concise reader for the furiously intellectual insurrectionist–about-town, it laid the foundation for the true commercial success that would see the band lay waste to the mainstream less than five years later. That they did so in the absence of Richey Edwards their precariously driven poster-boy, and alongside Nicky Wire one half of the band’s compulsive kohl-smeared lyric factory, is an eternally tragic missed opportunity for cultural insurgency of titanic proportions.

Methadone Pretty may not be one of the album’s stronger offerings, but its Marx-quoting opening gambit of “I am nothing and should be everything” says more about the societal circumstances that defined the band, the cultural artefacts it placed its faith in, and the targets it trained its sights on, than anything else that can be found either within its grooves or on its sleeve. This is the hopelessly bleak industrial landscape of Springsteen’s Nebraska (for ‘New Jersey’, read ‘Newport’) alloyed to the rama-lama glam-metal escapism of Hanoi Rocks. Edwards once reflected that, “the thing about Generation Terrorists was that the title was misunderstood. At the age of 10 or 12 everybody is full of some kind of optimism, yet by the time that they leave school they’ve given up on everything. In those five or six years your life has been dramatically changed and pretty much destroyed”

This was a fatalism writ large through much of Wales in the 1980s but to hitch that despondency to a militant political bandwagon driven by the New York Dolls flew provocatively in the face of a British music scene still in thrall to the cultural impact of ecstasy and dance culture. It’s an approach that on paper should have fallen flat on its face, and in parts (Crucifix Kiss, the notorious yet now strangely vindicated Nat West-Barclays-Midlands-Lloyds) that’s exactly what it does, but the instances where it prevails – occasionally achieved by sheer brute determination alone – define the cultural power and infinite possibility of rock’n’roll to craft purpose from despair and to reinvent the outsider as the avenger.

Shamelessly ludicrous and calculatingly overblown in parts, a stone-cold masterpiece it certainly isn’t, but as an enduring testament to the limitless boundaries and fearless ambition of four young working-class men who refused to have anything other than ideas fixed resolutely above their station Generation Terrorists is utterly peerless, and to those who were motivated by its cultural tinderbox of insurrectionary politics and outsider art, nothing short of inspirational.

Wales would belatedly clutch the band to its heart soon enough but at the time of Generation Terrorists, only a year or so after using one of their own record sleeves to proclaim that ‘Nationalism is a Created Product’, the Manic Street Preachers’ own ruthlessly honed self-belief required nothing as seemingly out-dated and petty as the validation of their countrymen.

In 1992 the future was still unwritten, but baby, they were born to run. Generation Terrorists