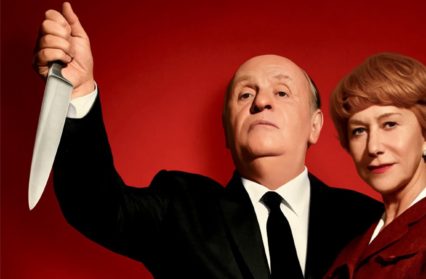

Jim Morphy reviews Hitchcock, directed by Sacha Gervasi, and starring Anthony Hopkins, Helen Mirren, and Scarlett Johansson.

We’ve seen an awful lot of Hitchcock recently. The British Film Institute gave us a three-month tribute to ‘The Genius of Hitchcock’ as part of the London 2012 celebrations. Vertigo usurped Citizen Kane as the greatest film of all time in Sight and Sound’s decennial poll. There have been film restorations and box-set releases. Here in Wales, Chapter cinema ran a Hitchcock series. The Christmas TV schedule was Hitch’-heavy, with the centrepiece being the HBO-produced The Girl, which laid bare the director’s sexual harassment and bullying of Tippi Hedren.

Alongside all this, any number of articles have sought to define and explain Hitchcock and his work. On one side, he’s one of the greatest directors that ever lived. On the other, he’s the repressed, sadistic letch who lived out his fantasies on-screen, and, at times, on-set. Of course, very likely, he was both. Having the repulsive eye of a voyeur and being a cinematic genius are not mutually exclusive. In fact, a case might well be made that having the first is a necessary characteristic of the second. Hitchcock’s twin reputations comfortably co-exist, feeding endless speculation over the degree to which his dark desires and his films overlapped.

The definitive-sounding, if distinctly undefinitive, Hitchcock is the latest work to take on the famously-rotund director. The film revolves around the relationship between Hitchcock (Anthony Hopkins) and his co-director/talent-scout/ editor/ screenwriter/cook/wife Alma Reville (Helen Mirren) during the making of Psycho. We see how, after being shunned by the moneymen, Alfred gambles the couple’s own fortune and his reputation on making a cinematic success of Robert Bloch’s schlocky novel.

Hitchcock turns out to be a disappointingly by-numbers light drama

The difficulties of the film shoot, Alma’s liaison with a handsome writer, and – entirely bizarrely – the spirit of serial killer Ed Gein (the inspiration for Bloch’s book) all conspire to put a strain on Hitchcock, who resorts to food, liquor and the company of drop-dead gorgeous actresses for comfort. The film shows glimpses of a Hitchcock rarely portrayed: the classic studio-system director is now the reckless outsider, and the worshipper of ‘blondes’ is now the one being driven to despair by his partner’s wandering eye.

Despite this potentially interesting take on things, Hitchcock turns out to be a disappointingly by-numbers light drama – certainly, it suffers in comparison to the rather more leftfield and provocative The Girl. The script stutters, the relationships fail to convince, and when the tension threatens to rise, what we know happens, happens, and in boringly straightforward fashion: Psycho is a success and the couple stay together and get to keep their swimming pool. By the end, it’s a sentimental love story – this happy portrayal is certainly sickly, and is perhaps even downright objectionable when we consider the behaviour of Hitchcock as shown in The Girl and chronicled in the work of biographer Donald Spoto.

This isn’t to say Hitchcock is without its qualities. Anthony Hopkins gives a star-turn in the lead, even if he is in unlifelike heavy prosthetics and doesn’t even attempt to match the voice of Hitchcock. Rather, Hopkins’s portrayal succeeds by giving us an arch, deliberate, egotistical, chairman-of-the-board type Hitchcock in company, and a troubled, self-pitying Hitchcock when alone. Hopkins plays the type of character, rather than trying too hard to be Hitchcock himself. This works well. While we get glimpses of Hitchcock’s repulsive behaviour, this is an altogether more sympathetic portrayal than that offered by Toby Jones’s also-impressive turn as the director in The Girl.

Helen Mirren also impresses as a super-smart, sparky Alma – the Alma we could have done with facing up to Hitch’ in The Girl rather than the largely subservient (and supposedly more historically accurate) Alma that Imelda Staunton gave us in that film. Scarlett Johansson gives a frothy showing as a frothy Janet Leigh, who is shown to worship the ground Hitchcock walks on. Jessica Biel plays Vera Miles, an actress who, like Tippi Hedren, had to deal with unwanted attention from the besotted director – a storyline Hitchcock could have made a lot more of. In fact, there are a number of potentially interesting plot threads, but director Sacha Gervasi (Anvil! The Story of Anvil) goes after the safest – the wrong – ones.

ultimately, if you’re looking to get to the bottom of Hitchcock the director, you’re much better off elsewhere

Hitchcock offers some neat self-reflexive touches that hint at the smart metafilm this could have been, such as a framing device using Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Alma in shower scene-like underwear, and a black bird landing on the director’s shoulder. And the film is shot in beautiful light, giving it a suitable Hollywood gloss. Certainly, there are crumbs here for the Hitchcock-obsessive and even for the casual filmgoer.

But, ultimately, if you’re looking to get to the bottom of Hitchcock the director, you’re much better off elsewhere: start with Psycho, then move onto The Birds, then Rebecca, then Vertigo, then Rear Window… If you want to get to the bottom of Hitchcock the person, well, who really knows? But perhaps best start with Psycho, then move onto The Birds, then Rebecca, then Vertigo, then Rear Window. As even if you don’t buy the notion that Hitchcock’s films are a faithful representation of his personal desires, at least you’ll be watching absolute, undoubted cinematic genius.

Hitchcock offers infinitely more than Hitchcock.

Banner illustration by Dean Lewis