Since 2009, the contemporary amplified ensemble Icebreaker have been collaborating with London’s Science Museum on an investigation of the relationship between electronic music and live acoustic performance, starting with Brian Eno’s Apollo and now continuing with Kraftwerk Uncovered. Apollo toured internationally in 2010-12 and Kraftwerk Uncovered will do the same from 2014. Icebreaker’s Artistic Director James Poke writes about the project and the light it has thrown upon this iconic material.

1983 saw the release of Brian Eno’s album Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks. The music is a collaboration between Eno, his brother Roger Eno and guitarist Daniel Lanois, although all but one of the tracks, a Lanois guitar solo called ‘Silver Morning’, are at least co-written by Brian Eno. The music was intended as a soundtrack to an otherwise silent film by Al Reinert, called For All Mankind, to be based on NASA film footage from the Apollo moon landings. However the film was much delayed, because there is such an enormous amount of footage (NASA filmed pretty much everything they did) that it apparently took Reinert a full year just to watch it, before he could start the process of creating and editing the film. And when the initial cut was deemed too arty for cinema audiences, further time was taken to develop the film into a more conventional documentary, which finally gained cinema release in 1989. The resulting film did use music by Eno, but not all of it was from his Apollo album, and the music was used much more in the background than was intended in the original concept.

By this point, the music had long since had a life of its own. The album marked a continuation of musical ideas explored in Eno’s ‘Ambient’ series of four albums, which had started with Music for Airports in 1978, and finished with Ambient 4: On Land, from 1982. However, Apollo expanded the stylistic range by incorporating elements of country & western: the reason for this was Eno’s discovery that each Apollo astronaut had been allowed to take a single cassette with them into space – and all but one of them had selected country music. As a result Eno came up with the idea of producing what he has called ‘zero gravity country music’. The country-influenced tracks, helped by the presence of Daniel Lanois’s characteristic pedal steel guitar, offer a contrast to the more bleakly ambient tracks elsewhere on the album. Otherwise the music is very consistent with the ‘Ambient’ series, a sequence of starkly minimal electronic tracks, full of soft attacks, floating in reverb, but somehow echoing the desolate coldness of space.

So how did Icebreaker come to be playing a live version of this music? To fast forward several decades from the original album, we find ourselves in early 2009, the year of the 40th anniversary of Armstrong and Aldrin’s small and giant steps. Tim Boon, head of research at the Science Museum in London, and a music enthusiast, came up with the idea of putting on a live version of the score at the museum’s IMAX cinema, in conjunction with a version of For All Mankind, as a celebration of the anniversary. Ed McKeon of the Society for the Promotion of New Music was asked by Tim to develop the project – and it is at that point that Icebreaker were asked to become involved, along with well-known pedal steel guitarist B. J. Cole.

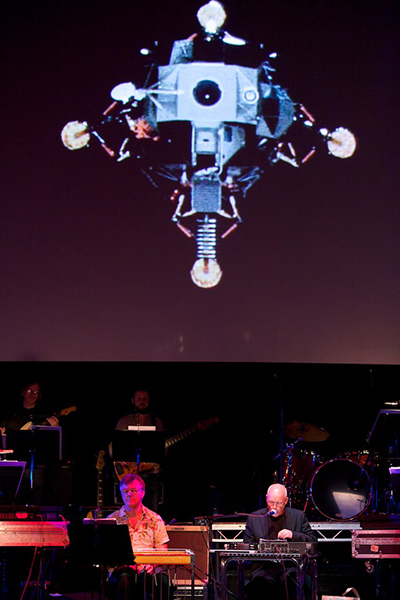

with Icebreaker at Brighton Dome

Photo by Matthew Andrews

The Transformation of Apollo for Live Performance

The first issue that needed to be addressed was how this essentially electronic and entirely studio-based music could be transformed into a live experience. How do you take the electronic sounds, with their own very distinct ‘atmospheres’, as in the album’s title, and make them work for ‘conventional’ instruments, particularly when in many cases the sounds are not even pitches, with deep bass rumbles, strange space noises, and clicks and bleeps?

The person who was enrolled to answer those question was South Korean composer Woojun Lee. Ed McKeon had come up with the idea of inviting SPNM composers to submit proposals for arranging the work, and Woojun was one of them. He was not immediately the front runner. When Ed and I examined the various submissions to produce a three-person shortlist for Brian Eno to select from, Woojun’s submission had none of the required documentation (indeed I believe he had failed even to put his name on it). However Woojun had supplied a recording of an ambient orchestral piece he had written, and once we started listening to it, it was so mesmerising that we were unable to turn it off. We had no real idea whether he had the arranging skills to take on the project, but he had to be shortlisted on the basis of his amazing piece – and naturally he was the one that Eno chose.

Woojun’s approach to the arrangement was very innovative in terms of how it dealt with the sound world, using certain techniques which were evident in his orchestral piece. A key element is the use of instruments fading in and out of notes, but overlapping so that the sound of one instrument takes over from another. This creates a very unusual effect as you hear the sound of, say, a flute, slowly transforming into the sound of a violin, so that you are unclear exactly which instrument you are hearing. This helps to create a wider palette of sound, and a counterpart to the changing nature of the original electronic sounds, and is perhaps key to why his arrangement is so successful.

In addition Icebreaker’s amplified sound naturally offers a wider range of sonic options than would be available in a conventional classical ensemble. Not only electric guitar and bass, but electric strings and keyboards offer ways of altering their sounds, and Icebreaker also has some more unusual instruments available, such as accordion and pan-pipes.

Where the sounds of the original were particularly abstract, Woojun took a more creative approach. A good example is ‘Matta’, the most abstruse and impenetrable of the tracks on the album, with little in the way of pitched material. Woojun’s approach was to imitate the strange whale-like noises by means of a cello’s sliding natural harmonics; meanwhile, an abrasive high-pitched sound is represented by two piccolos, keyboard and violin in ‘unison’, but with the players deliberately asked to allow the pitches to waver fractionally, so that a ‘beating’ effect between the instruments results.

So on the exact day of the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11’s arrival on the moon, the first performance took place of the new version, introduced by a talk by Brian Eno himself. For Icebreaker this represented something of a departure from our usual highly rhythmic, post-minimalist sound, although there is some static drone-based music in the repertoire. For B. J. Cole, the performance was significant, because for many years he has been developing ways of using pedal steel guitar in an ambient context – and the original inspiration for those ideas was indeed the unusual use of the instrument on the original Apollo album. The resulting work is in many ways a restoration of the original concept, with the film cut to include only visually significant material, without any soundtrack, and with the music that was originally composed to go alongside it.

Electronic Versus Acoustic – Kraftwerk Uncovered

The question of the relationship between modern electronic music and live performance is an intriguing one. With the ever increasing presence of technology in music, it is inevitable that the musical future will be an electronic one, at least in part. So how will the electronic element relate to the acoustic, the computerised to the human, and how does existing music of both types fit into the future world? Of course we can’t really answer that question, but by investigating, in a practical sense, the relationship between the different classes of music of the last thirty or forty years, we can perhaps shed some light on it.

It is in that context that Icebreaker is continuing the exploration of this relationship with further projects in collaboration with the Science Museum. Icebreaker’s next project is Kraftwerk Uncovered, a reworking of material by the electronic pioneers in a new score by German musician J. Peter Schwalm, which will premiere at the museum’s IMAX cinema on January 24th 2014, with a new film by Sophie Clements and Toby Cornish.

To explore Kraftwerk’s music seemed like a logical next step, especially as Tim Boon is a Kraftwerk enthusiast. Eno and Kraftwerk can be seen as two overlapping poles of electronic music in the 1970s and early ’80s. Whereas Eno pioneered ambient music, Kraftwerk can be seen as the innovators of pulse-led electronic music, which in due course gave rise to house, techno and modern dance music in general: indeed there is virtually no modern electronica which doesn’t carry the influence of at least one of these artists.

In the case of Kraftwerk’s music, unlike Apollo, the music has been and continues to be performed live. However, Kraftwerk’s own live performances are an increasingly stylised electronic reproduction of their albums, with all acoustic and traditional instrumental elements removed, and their famous robotic approach to presentation, in which the human beings become virtual automatons: in other words the human element is technologised. Icebreaker’s approach is the opposite, namely to humanise the technological, and, as in Apollo, to look at how the electronic sound world can be re-imagined in a live instrumental framework.

Important to this is a re-discovery of Kraftwerk’s avant-garde roots: before the famous Autobahn album launched them on the world stage, they had been much closer to the experimental music of other ‘Krautrock’ bands such as Can and Neu!, combining a progressive jazz rock with electronic experiments, including tape manipulation of material. This includes tracks such as ‘Harmonika’, based on a slowed-down mouth organ, or ‘Atem’, which is effectively a musique concrète piece, manipulating the sound of breathing, or ‘Kling-Klang’, in which the music is gradually vari-speeded up a minor third, before suddenly being slowed down until it stops. This early music is interesting because it combines the acoustic (particularly Florian Schneider’s flute-playing) with electro-acoustic effects, mostly drawn from the world of electronic art music. Even on Autobahn, the experimental is in play: despite the success of the shortened ‘single’ of the title track, the full length version (which runs to more than twenty minutes) has distinctly strange and dissonant passages, and side two contains mostly obscure ambient material (this is an album, I suspect, where most people’s original vinyl copies are very worn on side one and pristine on side two).

For Icebreaker an additional aspect is particularly intriguing, namely the relationship of the Kraftwerk / Eno styles of music to experimental classical music of the time, particularly minimalism. Minimalism can be broken down essentially into two different streams: the familiar repetitive minimalism exemplified by Steve Reich and Philip Glass, and the drone minimalism by the likes of LaMonte Young, Phil Niblock or Eliane Radigue. The relationship between these strands and the stylistic positions represented by Eno and Kraftwerk respectively is striking, but should not be surprising: Eno, too, comes from experimental roots, working with Cornelius Cardew’s Scratch Orchestra, and performing alongside Michael Nyman and Gavin Bryars in the Portsmouth Sinfonia. Icebreaker is a band that plays predominantly minimalist and post-minimalist music, so it is important for us that this music represents merely different facets of a dominant strand of new music from the period, regardless of whether they have traditionally been filed under ‘classical’ or ‘non-classical’.

This project is an ongoing one, which is envisaged to include further projects exploring the music of more recent significant electronic musicians, including Barry Adamson and Venetian Snares. Each offers a slightly different challenge to arrange or re-work, and presents elements which emerge from later technology, in the case of Venetian Snares, for instance, the highly sophisticated and complex drum programming. Nevertheless, the exploration remains extremely rewarding.