Ahead of the release of Later, Carl Griffin talks to T.S. Eliot prize-winning poet and academic Philip Gross about his craft and the future of poetry in the community.

Carl Griffin: If the collection Deep Field is your attempt to dredge the silence of your father’s several languages (due to deafness then, later, aphasia), how much easier is expressing your feelings through writing rather than ‘talking’ about the diminishing of a gift of a vocabulary? Do you struggle to articulate yourself verbally, without the badge of fifteen drafts?

Philip Gross: If we were having this conversation in real time, rather than by e-mail… Sorry, is that a trade secret?

Yes.

Philip Gross: If we were talking in person, you might have an answer to the second question.

It’s true, as poems in Deep Field explore, that much of my childhood and my teens was hedged about by stammering, the embarrassment and fear of it… and the fault lines of that are still audible. But equally true that wrangling with words made me a writer – not as an avoidance but as a way of going straight at language, trying to get my hands on it. I’ve made my life in language; I perform, give talks and interviews, I teach, and some of my best thinking happens live, in conversation.

I also had speech problems in my teens, but for me the most penetrative thinking comes through writing, and reading, poetry.

Philip Gross: The two states are closer than you might think. Real quality conversation is as much about listening, paying attention to words and beyond them, as it is about holding forth. It has quietnesses in it – if you like and trust each other, if you’re really interested. Don’t you think what I’ve just said about good conversation could be describing poetry?

This is coming round to your assumption about the ‘fifteen drafts’. Yes, I’ve sometimes been seen as a technical kind of a writer, crafted to the point of fastidious. After thirty years I guess I have that sort of craft inside me, but a lot of the poems in the books we are talking about were written quickly, almost on the hoof. I’m a writer with discipline, but one of my (learned) disciplines is that of finding ways to dodge around the rather dogged answers that too-conscious thinking brings. And sometimes life just is so busy or so immediate that a scribbled note is how it has to be. You look at it next day and you think, Did I write that?

Which is like conversation… I know a good conversation when I, when both people in it, find themselves saying things that we didn’t expect – things we didn’t know we thought until we said them, and maybe wouldn’t have got to by ourselves or with anyone else. The same goes for those moments when you know that something has happened in a poem. And that is a conversation, too.

You are known for your collaborations. Do artistic collaborations necessarily add deeper extensions to these conversations?

Philip Gross: When you are collaborating with another writer or someone working in another medium, that’s where some of the best creative surprises in my life have come from, and every collaboration is different, just like any relationship that matters.

The best are the ones where you start to let each other in to parts of the process you don’t often share – the notebooks and the first responses, the improvised moments in another form. Maybe the deepest case of this was with the late and fine engraver Peter Reddick, working on a book called The Abstract Garden. He was already in his eighties, but his willingness to trust me with his sketchbooks, and to let the process lead him out of lifelong habits, was something I will not forget.

Collaboration is a relationship, of course. But writing alone is conversation too. It just happens to be a conversation with people who aren’t there, or aren’t real, or died five hundred years ago, or spoke another language. Sometimes, maybe always, writing is a conversation with the silence. (Don’t forget that I’m a Quaker. What I’ve just said could be talking about a Quaker meeting too.)

I’m tempted to delete the brackets from that last sentence. Deep Field is full of brackets. As a reader I found them distracting and unnecessary, while other readers found them directional.

Philip Gross: Well, look at what I’m doing here, with you. (That’s ‘here’ in a virtual sense, though I’m in Penarth, and you? Who knows – maybe Newport.)

No, I escaped from there some time ago.

Philip Gross: I’m trying to set down simply how I think. OK, I’m hamming it up a bit for you, but don’t you see at the same time the shape of a thought going forwards, through the sentence, and at the same time spot in the corner of your eye the side-points, the marginal notes, the necessary qualifications – stray connections that you know you may never come back to if you don’t nod towards them now?

When we are talking face to face, you hear the brackets in all kinds of non-verbal ways. On the page… Well, the shape and punctuation of the words in print are just a way of mapping how a thought, or little flock of thoughts, actually move. I’m very aware that poems both move on, like speech does, and at the same time they are all there, whole and static on the page. Both things are true. Isn’t that a wonder?

Deep Field, though, that was a conversation. In some ways it was the most intimate conversation I ever had with my dad, even though so little of it, by the end, occurred in words. It was also a conversation with language / languages; in that, he and I weren’t so much face to face as alongside.

Don’t assume too easily that the job of Deep Field is to express my feelings. Clearly there were, there are, layers and layers of feelings, some of them from me the adult, some from me the child, and there are glimpses of my son and grandson in the poems too. But it’s also an attempt to go through that strange territory alongside my father, the place he’d unwittingly opened a door to, as much as I could.

To see this as a sad book would be to miss the strands that mean the most to me. It is also a celebration, partly of an old man’s courage and good humour, partly of that astonishing edifice of language. (How do we do it, I asked more and more as he could do it less and less.)

He would also, in earlier years, have been alongside me in the way the book tries to think as well as feel its way forwards, as well as it can. It isn’t unfeeling to try to see things clearly, and to use what knowledge you happen to have – call that ‘intellect’ maybe – to help. He would certainly have been with me in seeing his struggles as a window opening into bigger questions – about human language, about memory, how these things makes us what we are, what we might be without them. Apart form being the questions of his age, and my age too, from now on, aren’t these coming to be the questions of this age, when so many more of us will not die of the physical causes that would have taken us previously, but will live to face this?

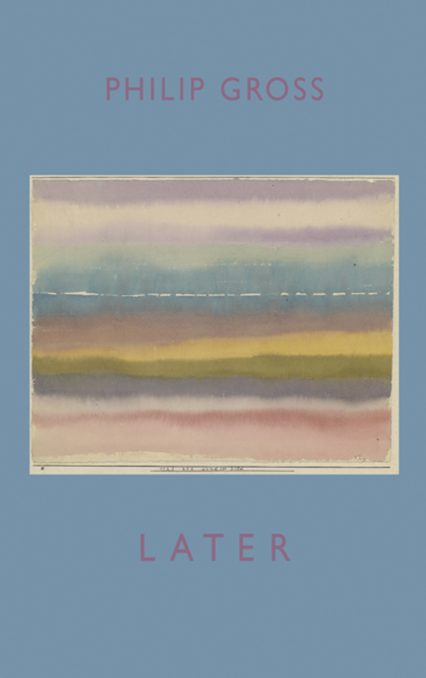

You have a new collection, Later, out later this year. What is it about?

Philip Gross: Later is again my father’s book, it comes from the last year of his life, when language was gone and we were pretty much down to the basic human and animal stuff we all share. Neither this nor Deep Field (nor the much earlier The Wasting Game, about another illness in the family) is a case history; I can’t be the clinical observer, because increasingly what I saw occurring in his language, in the un-wiring of his brain and failing of his body, was only what could equally, and one day quite likely will, apply to me. And anyone.

Maybe the most expressive page in the book is right in the middle, and there’s nothing on it. Before it, the poems are before my father’s death; after it, they are, well, later, testing all kinds of ways of imagining what comes after a life, though an ‘afterlife’ is not the point, for me. In between the before and the after, I hope the blank page speaks for itself.

In previous collections you have been concerned with water and maps, but your poetry never lacks people? Do you think concentrating on nature and never people, or vice-versa, would lead to a hollow volume?

Philip Gross: Ah, water… The Water Table, the book that had the luck to win the T.S. Eliot Prize, is pretty much awash with it, of course. But so is Deep Field; the long sequence about the flux of language we came back to is called ‘Something Like The Sea’. I was born near the sea, in Cornwall, and brought up in Plymouth, a city that’s defined by it, geographically and as a port and dockyard. I lived much of my life in Bristol, another great port… and now Cardiff, and the Severn estuary.

The Water Table was a gift of the estuary, and of driving across the bridge, before I’d moved from Bristol, and seeing it different, day after day.

Was I writing about ‘nature’? About a place, certainly – one with such a force of… well, being itself, that it was hard not to think of it as a personality. But I’m not a Romantic, who sees it as the job of nature to embody our emotions for us (it surely must have better things to do?). And I’m not an eco-poet in the sense of Deep Ecology — thinking that nature or place has a kind of being that we can give impartial voice to, leaving ourselves out of the question entirely. Looking at the estuary I was sure of two things. One was that most of what I saw by that obsessive staring at the water would be not the water itself (which in its pure state after all is colourless and odourless and tasteless) but what was floating on it, or suspended in it, or refracted by it or reflected in it – all the context of it, much of which was human, either outside in the world or inside me. The other thing was there was something there — something huge and hugely powerful, that would always escape and be bigger than anything I said about it. Something that was assuredly not me. Now, isn’t that a relief?

Or to put it another way: even when you’re looking out for being surprised, the variety of ways surprises happen can be quite surprising in itself. Sometimes it comes by stillness and that crazily persevering sort of attention — as in I Spy Pinhole Eye, a whole book about gazing at an obsessive set of photographs which in themselves were an obsessive meditation on the most functional thing, the concrete footings of electricity pylons, on earth.

Other times it comes by speed, on the hoof, as I said. Or by playing games with other people… or by making a space for yourself. Or by a leap of thought, or an unguarded feeling. Or by eloquence, or by the breakdown and failure of words. Take your pick.

Or rather, you don’t take your pick. You just keep working. Sometimes it picks you.

You might also like…

Philip Gross’s new collection, Later, published by Bloodaxe, is out in September.

Later