Dylan Moore reviews two retellings of the Mabinogion in See How They Run by Lloyd Jones and Tree of Leaf and Flame by Daniel Morden.

In the ‘Afterword’ to See How They Run, his wildly inventive take on the third branch of the Mabinogion, ‘Manawydan, son of Llyr’, Lloyd Jones posits an interesting theory. Praising the popular Seren series which will itself reach a conclusion next year, Jones imagines that ‘a century of English writing by people with deep roots in the Welsh tradition’ is coming to an end. On the basis that there are ‘only a handful’ of writers left in Wales who work in both languages, Jones predicts, boldly, that our written culture will be divided along linguistic lines. ‘A new future beckons,’ he concludes, before adding, almost as an afterthought, ‘I hope you enjoy my book.’

I am happy to report that I enjoyed See How They Run immensely, and would urge potential readers to look beyond the rather prosaic title and uninspiring blurb instead to delve into the multi-coloured, multi-layered riches that lie within. Jones credits Niall Griffiths’ contribution to the series – The Dreams of Max and Ronnie – for the ‘boisterous sulphur’ of his own attempt to twist the liquid gold of the original story into something purposeful and resonant in the twentyfirst century, and there is certainly something of Griffiths’ refreshing irreverence here. Jones switches the viewpoint character to Llwyd, the avenger, casting him as an academic researching the life and times of Dylan Manawydan Jones, the hero himself. Better known as ‘Big M’, he is a second row forward and the hero of all Wales, not to mention many parts of Ireland, where shrines have been set up in pubs commemorating a legendary rugby match that Wales won at the price of the death of Big M’s brother.

by Lloyd Jones

See How They Run makes much of the Irish element of the Third Branch, with good reason. Swapping a battle for a rugby match would seem like a straightforward adaptation, a simple way of updating the story and fulfilling the series editor’s brief. But it is not rugby that is most important (although, this being Wales, of course this is a huge statement about national identity too) – it is Ireland. Jones’ choice to make Llwyd McNamara an academic is inspired. At one point an English colleague urges ‘get out of that Celtic scene, it’s as dead as a doorknob… Celtica’s gone, it’s dead and buried. Look to America, that’s where it’s at.’

Jones captures a magic largely absent from the modern world, but that glints beneath the surface, existing particularly in stories

Of course, what See How They Run and the entire Seren series demonstrates is the exact opposite. Celtica, if you want to call it that (and I don’t), is very much alive. Jones calls the ‘blood ties and resultant cultural connections’ between Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall and Brittany a ‘special relationship’, a deliberate echo of the ‘arranged marriage’ between Britain and America. His novella animates the idea that ‘global US pop culture… has swamped Britain and skewed the island’s cultural axis’. The book is, as is the whole series, a reclamation of a cultural inheritance, but it also welds together the ancient mysteries of the Mabinogion story cycle with the modern – and postmodern – world.

At the heart of the story’s symbolic system, as well as the mouse motif borrowed from the ‘original’ – here evidenced as a tattoo adopted by the whole Welsh rugby squad – is a memory stick. Described as ‘lizard green and semi-opaque… beautiful, nicely proportioned, slightly sad’, in Jones’ vision this workaday tool of the modern world becomes a mysterious, talismanic object. ‘No manufacturer’s name’ appears, ‘merely a symbol showing radiating wave.’ In the hands of Lou – Llwyd forgoes his ‘pale’ forename – the lifework of Dr Dermot Feeney contained on the USB device becomes ‘Someone else’s memories; someone else’s lifeblood in a fragment of plastic… another man’s genius.’ But as the character ruminates darkly over his course of revenge, it is the sparkle of the author’s own prose that illuminates and thrills: ‘Dimly, he could see its inner workings; rows of tiny components glinting like a canteen of silvery fish in a milky green sea.’ Here, and elsewhere in the book, Jones captures a magic largely absent from the modern world, but that nevertheless glints beneath the surface, existing particularly in stories.

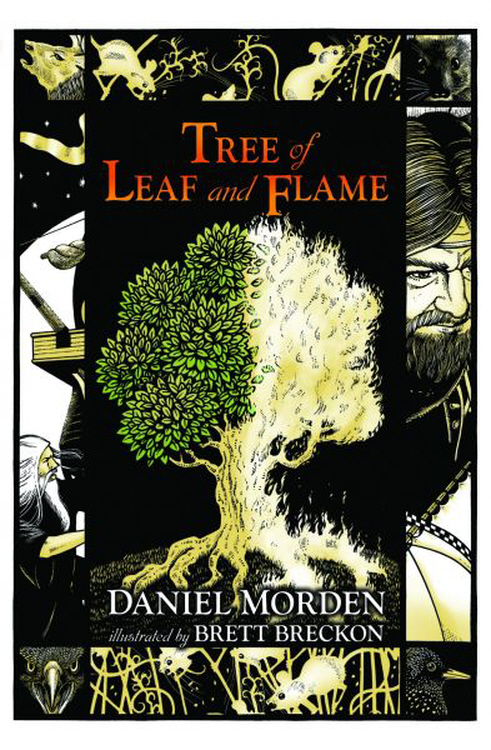

by Daniel Morden

Storyteller Daniel Morden’s new book Tree of Leaf and Flame is a much more straightforward recounting of the Mabinogion tales. A companion volume to his wonderful Dark Tales from the Woods, a collection inspired by Abram Wood, the celebrated King of the Gypsies in Wales, Morden’s professed aim was to ‘write a book I would have enjoyed reading when I was ten.’ Adult or child, the reader’s enjoyment comes easily because there is such an obvious delight evident in the stories’ telling. Although there are no career academics or rugby players and no references to The X Factor or Don DeLillo novels in Morden’s work, he has nevertheless tinkered with the tales. While Seren have commissioned ‘full length’ versions of all of the tales featured in Lady Charlotte Guest’s nineteenth century English translation, Morden manages to squeeze the traditional ‘Four Branches’ of the Mabinogion into a slim volume of under a hundred pages. In an afterword, Morden describes the process of telling and retelling tales as akin to turning a kaleidoscope. Reminding us that even the ‘original’ tales are merely ‘fragments of an elaborate pattern’ Morden defends his decision to ‘suit the tastes of the time’.

In addition to the precise, chiselled brevity of the stories, there are two striking things about Tree of Leaf and Flame. First, there are the scraperboard illustrations of Brett Breckon, whose Dark Tales from the Woods image of a man holding out his own eyeballs in his hands while blood trickles from the empty sockets is legendary in classrooms across Wales. Second, there is the powerful interjectory nature of Morden’s narrative voice.

Morden possesses the true storyteller’s gift – an inheritance perhaps, it might not be too much of a stretch to say, from the ancient bards – of holding an audience rapt.

The relationship between writing and drawing is symbiotic and such is the atmospheric fit between Morden’s spare prose and Breckon’s bold imagery that one can only assume either a very close working relationship or a telepathic level of understanding, or both. The restriction of black and white reproduction within the pages of Pont’s beautifully produced miniature hardback only serves to highlight Breckon’s stark use of contrast, the light and shade in his images reflecting the interplay between good and evil which courses through the stories. In addition to the full-page plates scattered throughout – Pwyll at the edge of the forest, Rhiannon discovering the ‘death’ of her child, Lleu’s spear shattering Gronw’s body to the backbone – each branch has its own iconic symbol: the stag, the raven, the falcon, and, of course, the mouse. In fact, perhaps inspired by concurrent reading of See How They Run, my favourite of the illustrations in Tree of Leaf and Flame is the one of mice stripping bare the Dyfed fields of their waving wheat.

And my favourite thing about the stories as told by Morden, as it is in his live performances, is his interjecting tone. Often with the aid of memorable repetition, Morden possesses the true storyteller’s gift – an inheritance perhaps, it might not be too much of a stretch to say, from the ancient bards – of holding an audience rapt. Here it is the phrase ‘I wish I could say that this is the end of our story.’ Every time we reach a point where things have settled, where there is potential for a happy-ever-after, the narrator reminds us that these are not ‘fairy stories’; these are myths that are part of our heritage. We might, like the Seren series, be able to adapt and to build on them; we might be able to turn the kaleidoscope, to see the fragments falling in a different pattern, but there is something in their essence that we cannot change.

That is what Llwyd McNamara was looking for in the depths of a USB stick, in the spell of its mysterious symbolic power and it is what Daniel Morden has captured in – somewhat ironically perhaps – plain English. And if we revisit Lloyd Jones’ idea in the light of this – that somehow these new tales from the Mabinogion represent a break from as well as a link to the past – we might begin to see that this is part of what these stories have been trying to teach us all along. It is not the fragmentary or arbitrary details that inform our identity, nor is it the way we tell the stories nor even the language that we use; it is the very fact we have a story at all.

Recommended for you:

Gary Raymond reviews an episode of BBC Four‘s The Secret Life of Books, which focuses on The Mabinogion and questions its unusual choice of presenter.