Hoddinott Hall, Wales Millennium Centre, Cardiff, October 20, 2017

BBC National Orchestra of Wales

Guest conductor: Robert Spano

Soloist: Ashley Riches (bass-baritone)

Shostakovich: October

Musorgsky: Songs And Dances Of Death

Musorgsky: Song Of The Flea

Liszt: Mazeppa

Scriabin: Le Poème De L’Extase

A travelling Welsh Music Festival in 1920 fetched up at Mountain Ash, where the London Symphony Orchestra under Albert Coates performed Scriabin’s Le Poème De L’Extase to an audience estimated at between 5,000 and 7,000 in the biggest pavilion the Cynon Valley had ever seen. This takes some understanding, both in terms of how carping English critics at the time saw music making in Wales (sentimental, crude, even barbaric) and of what Welsh music lovers were prepared to turn out for in droves. The festival was devoted to ‘contemporary’ music – Elgar, Bantock, Holbrooke, Vaughan Williams and others – and included the world première of Delius’s En Arabesk when the LSO reached the Central Hall, in Newport, Gwent. The now-defunct Newport Choral Society had been practically well prepared for the honour of unveiling the Delius work, in which Percy Heming was the baritone soloist. Coates had known Scriabin and was a champion of Le Poème. According to The Musical Times, the Cynon Valley audience was composed mainly of ‘the so-called working classes – miners, engineers, and the like’ and was enthusiastic to the point of calling on Coates to repeat the 25-minute work. Extraordinary, in all sorts of ways.

The BBC NOW’s choice of Le Poème at this concert, therefore, was not only part of the latest commemoration of one hundred years since the Russian Revolution but also a local association of the work with unrest. Back in Mountain Ash, those workers clamouring for it to be reprised were central to a community basking in the aftermath of the Great War and just six years away from the General Strike. Perhaps they saw in its orgasmic waves of sound some sort of relief from military conflict as well as the prospect of victory in the coalfield battles to come. They certainly would have if it had been played as earnestly as it was at this concert. ‘Ecstasy’ for Scriabin, though, meant vigilance and raised awareness, rather than exhilaration, though the combination of moods today is irresistible.

In one sense it’s an involved, sonata-form crescendo with a couple of climaxes, the last one blazing; in another, it’s almost a nascent trumpet concerto, the bright contribution of the orchestra’s section principal trumpet, Philippe Schwarz, in riding the crest of the wave, accorded a personal handshake by conductor Robert Spano after he’d waded into the ranks. Spano’s control over Scriabin’s abbreviation of themes to motifs and the music’s resulting breathlessness was pretty much secure. A symphony compressed into a one-movement symphonic poem with conflicting episodes depicting protest, evil, and self-assertion necessitated short-winded development, but it was rolled out unhurriedly. What a shame the audience at Hoddinott Hall (but probably not on radio: it was a live broadcast) had to strain to hear percussionist Chris Stock’s euphoric glockenspiel part as the work surged towards the C-major incandescence of its conclusion. But by then everyone was in the throng and in raptures.

The orchestral version of Liszt’s Mazeppa, included to make this concert the latest in the BBC NOW’s tone-poem series, was performed with a pianistic attack, which to some might have been an ironic comment on its provenance as a keyboard piece and its limitations as subtle scene-painting. We got the picture, so to speak; it was exciting music played in an ever-onwards romantic fashion. Shostakovich’s October, the other symphonic poem in the concert, was musical rhetoric played in a celebratory style. If Shostakovich had written everything in this right-on, empty manner, the tone-deaf Soviet authorities wouldn’t have contacted him so often with their tiresome reservations and prohibitions; and Western music, perhaps not that part of it that moved music on, would have been the poorer. Music is essentially ineffable, beyond words; propaganda music is about words, those deemed by the committee to be correct and beyond cavil. It’s not a pretty sound. Wales’s Russia17 arts project, of which this concert was also part, is commemorating the Russian Revolution’s centenary, not celebrating it, which, some would say, is a bourgeois cop-out. In the West, ever questioning and never resolving, it will be ever thus.

Mazeppa tells a Russian tale. So does Musorgsky’s Songs And Dances Of Death, here and in Shostakovich’s orchestration given colourful treatment by Ashley Riches, a BBC Radio 3 New Generation artist and fast rising in the ranks of British bass-baritones. The louring bleakness of Musorgsky’s cycle of four songs seems to reflect the pre-Revolution despond which the coming upheaval intended to obliterate. Yet it speaks to universals, as Shostakovich spoke to life’s complexities and the right to be despairing in times of state-decreed optimism. With a capacious tone also capable of plaintiveness and poignancy, Riches became spokesman for souls in torment and the guises in which Death personified appears to them, from the mother of a dying child in the opening ‘Cradle Song’, via the ill-fated girl in ‘Serenade’ and the drunken peasant in ‘Trepak’, to the ghostly amalgam of Death and the dead in ‘The Field-Marshal’.

For the soloist it encompasses both narrative and role-assumption, Death itself being the vehicle of false assurance followed by triumph. Riches, in a fine, actorly, interpretation, made us pitiful and fearful; singing in Russian, he compunded our feelings. The episode in Goethe’s Faust in which Mephistopheles tells a story about a king who kits out a pet flea and makes it an inviolable minister of state might have been straight out of the Russo-fantastical canon. Mussorgsky must have sensed that when he set it to music. In this orchestration by Stravinsky, Riches commanded the visual attraction which platform performances of the song so often prompt, though with a bass more cantabile than profundo and thus less prone to invite Chaliapin-like awe.

The BBC NOW spreads itself thinly today. One wouldn’t be surprised to find it responsible for the soundtrack to a TV advert for BMW as well as the ever-expanding repertory that was physically beyond it fifty years ago, when it was the smaller BBC Welsh Orchestra. There are obvious dangers in this wider deployment, charitably described as versatility. But Spano, the much-liked conductor of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, must have found little evidence on this occasion to suggest that it was not sharper and on top of the music as a result.

Nigel Jarrett is a freelance writer and regular contributor to the Wales Arts Review. He is a poet, novelist, and story writer. His latest collection of stories, Who Killed Emil Kreisler?, was published last year. He is a winner of the Rhys Davies prize for short fiction and, in 2016, the inaugural Templar Shorts award. He also writes and reviews for Jazz Journal. He lives in Monmouthshire.

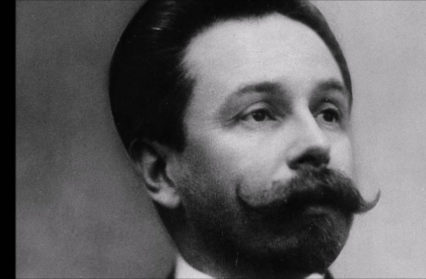

Header image : Scriabin

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.