Nigel Jarrett was at the opening of WNO’s latest offering in its Freedom-themed summer season with The Prisoner (Dallapiccola)/ Fidelio Act 2.

What’s the justification for staging Luigi Dallapiccola’s one-act opera The Prisoner alongside the final act of Beethoven’s Fidelio, rather than dropping the former altogether in favour of the whole of the latter? Welsh National Opera’s artistic director, David Pountney, would probably say ‘context’ and the need to provide as many illustrations as possible of the idea of ‘freedom’, the theme of the company’s summer season. It goes without saying that Pountney makes the job of grafting a truncated opera on to a complete one seem inspired. Inspiration is his watchword. The only risk, apart from the heresy of slicing in half Beethoven’s only opera, is ironic: that of elevating Dallapiccola’s to the level of such self-sufficiency and force that nothing is left to be said, even by Beethoven; except that Fidelio has a happy ending.

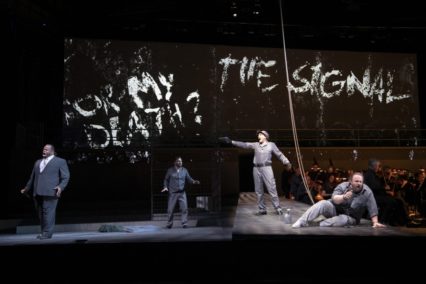

Misty Buckley, a rising star in the new generation of theatre designers, is key. Already helped by the similarity of theme in both works – incarceration and its despair – she embraces the WMC stage with glee, opting for an oxymoron: cavernous minimalism. To the right is the BBC National Orchestra of Wales, its members sounding like a bees’ nest as they buzz through their respective bits of Dallapiccola’s score before the off. Stage left, the other side of a dividing walkway, is a small cage or cell, space for some movement, and a downstage stairway to the depths in what would have been the orchestra pit. At the back is a balcony awaiting the WNO community chorus at the end of Fidelio and behind that, a cinemascope screen on which are projected blank walls with words from the libretto chalked up, as they are sung, like a jailbird’s outbursts.

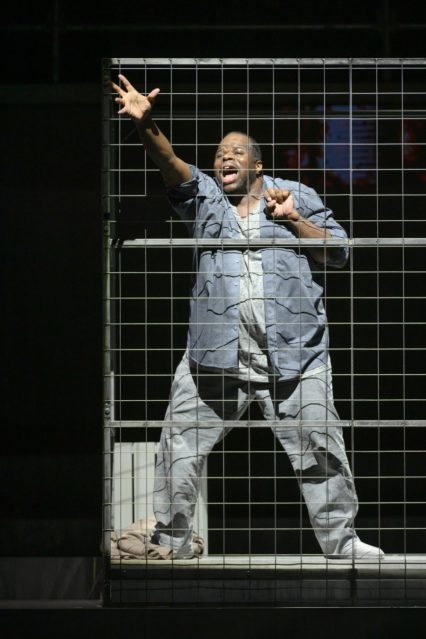

Only Pountney the magician could devise a season with so many unexpected subtleties, not least of which is the way the Dallapiccola opera segues into Fidelio on the same set after the interval and with the same creative team in charge. The savagery of outburst from Lester Lynch’s Prisoner in Dallapiccola’s opera, the tormented despair of Sara Fulgoni’s The Mother and the duplicity of Peter Hoare’s Gaoler, doubling as the Grand Inquisitor accompanied by two acolytes, signals the abandonment of hope before it materialises as a chimaera, the backdrop changing from a brick wall to a starry firmament wreathing a central tree of life. The tone (costume designer April Dalton), except in the Inquisitor’s garb and the projected line of flames representing damnation, is pallid grey, a complexion that seeps across to Fidelio, as it should, and to a point where for the imprisoned Florestan hope rather than death opens up again as the sole route to freedom.

Dallapiccola was an exponent of the twelve-note system of composition and was Italy’s leading exponent of it. But the music of The Prisoner confounds expectations for those who’ve never seen the opera, and who hope that despite the bleakness its Italian provenance might be more traditionally ‘operatic’. And so it turns out. Conductor Lothar Koenigs invests the orchestral music with a lyrical quality sometimes at odds with the anguish and desperation emanating from the voices to his left. For a work written in the middle of the 20th-century about the Spanish Inquisition, it’s an example of how a deliberately angular mode of writing can have its edges softened without suggesting that it’s trying to mitigate the misery floating about on it, or giving in to a more agreeable sound. More can be made dramatically of this hour-long work – placing the other inmates on stage, devising Piranesi-like scenes of punishment, making the Mother’s distress more febrile in terms of bodily movement – but Pountney refuses to prettify the basics: the choir of inmates is in the wings, there’s no blood and gore, the Mother nurses her grief in stillness. It’s as focused as desperation itself.

Jettisoning of the unwanted extends to Fidelio in the choreography of the prison scenes with Florestan (Gwyn Hughes Jones), Léonore (Emma Bell), Pizarro (Lester Lynch), and Rocco the gaoler (Wojtek Gierlach); especially in the moments surrounding the attempt to stab Florestan to death, when Leonore as Fidelio pulls a pistol to defend her husband and reveals herself as his wife. Before the revelation, Fidelio and Rocco fiddle with a hanging rope to open the cistern intended to be Florestan’s grave. (Such a metallic and grubby interment.) With no first act, we miss Rocco’s reluctance to kill Florestan on Pizarro’s orders and Pizarro’s decision to do the deed himself. We also lose from act one Léonore’s great recitative and aria after she’s heard about the plan to kill Fidelio; the famous Prisoners’ Chorus, a precursor of the lofty idealism with which the opera ends; and the love interest involving Rocco’s daughter Marzelline (Carly Owen), who thus appears with the prison porter, Jacquino (Osian Bowen), with little antecedent cause.

But again we get concentration that links directly with the end of The Prisoner. Hughes Jones carries on where his Dallapiccolan counterpart left off, in the three-part aria that ends with his vision of an angelic Leonore – ein Engel – the word chalked on the wall, with other emotive ones. The intensity continues with little break, culminating in some ardent ensemble singing and the duet between Léonore and Florestan of combined rejoicing – O namen, namenlose Freude (Oh inexpressible joy). It precedes the almost immediate heavy dollop of C major that dispels the opera’s louring cloud for the sun to shine through and for Daniel Grice’s Don Fernando to sing his calming speech about mercy. The WNO community choir troops across the balcony and the WNO company chorus down the walkway, both embodying prisoners freed. A flag flutters full sail on screen. The community singers put in a lot of work and the company is rewarded with stentorian singing and unanimity.

One needn’t be cynical to feel that the music is the elevating feature of the end of Fidelio rather than the happy-ever-after sentiment of the story. Yet without a way of rising triumphant above tyranny, humans fired by love would be a lost cause. Although other works might have complemented The Prisoner, few could have had the same effect in raising the stature of women as the agents of men’s salvation as that portion of Fidelio remaining after Pountney had courageously taken a knife to it. Moreover, Dallapiccola’s anonymous prisoner has a name and a future in Fidelio. It’s a masterstroke. Pountney is still an opera director for our times.

Freedom – The Exhibitions

WNO’s summer season at the Wales Millennium Centre, which has one more stage presentation to go – a production of Hans Krása’s children’s opera Brundibár (Bumblebee) on June 22 and 23 – is being supported by a series of free inter-active exhibitions illustrating the theme of Freedom.

It’s the theme that has run through all of the season’s productions.

All these exhibitions are available for viewing at the WMC until June 30. Brundibár is being staged at the WMC’s Garfield Weston Studio by WNO Youth Opera. It will be directed by WNO artistic director David Pountney and conducted by Tomáš Hanus, whose mother appeared in the original performances, the first of which was at a Jewish orphanage in Prague in 1942. But the composer and his set designer and the orphans were subsequently transported to Theresienstadt, and the opera was premiered there in 1943.

Earlier this month at the Temple of Peace, Chapter, and other city venues, there have been talks and debates on anti-slavery, refugees, free speech and artistic freedom, young defenders of human rights, crime and justice, the rise of nationalism, and the role of the young in democracy.

At the WMC, the augmented reality project Terminal 3 explores contemporary Muslim identities in the USA through the lens of an airport interrogation. The Last Goodbye is a work in which Holocaust survivor Pinchas Gutter toured the Majdanek Concentration Camp. Future Aleppo features young Mohammed Kleish, who dreams of being an architect and reconstructed a model of the city he had to leave. Freedom 360 is about refugees and highlights personal stories and journeys undertaken in fleeing conflict and seeking new places to live, including Wales. Fluorescence, written by Syrian artist Kinana Issa, explores themes of liberation and captivity. The Girls of Room 28 is an exhibition of notebooks, a diary, a scrapbook, photos, paintings, poems, letters, and drawings left by young girls who were murdered in the Theresienstadt Concentration Camp. The exhibition was created in 2004 in Germany to fulfil the wish of survivors to remember the girls and the adults who looked after them.

Nigel Jarrett is a freelance writer and critic. He’s a regular contributor to Wales Arts Review on music and other subjects. He won the Rhys Davies Prize for short fiction, the Templar Shorts award, and is the author of four books. He’s represented in the Library of Wales’s anthology of 20th– and 21st-century short stories.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.