The Library of Wales is a classics series celebrating the literary culture of Wales in the English Language primarily in the 20th century. It was launched in 2006 with five titles, So Long Hector Bebb, Border Country, Country Dance, The Dark Philosophers & Cwmardy. It has now fifty titles in the series with close to 100,000 books sold and can claim to have changed the perception of Welsh writing in English, reinvigorating the interest in classics such as Autobiography of a Super Tramp and Rhapsody, while bringing new light to titles that fallen from view such as Frank Richards’ memoir of army life in Old Soldiers Never Die and Leonora Brito’s Dat’s Love and other stories. Many of the titles are now being taught at university level while Poetry 1900 to 2000, an anthology edited by Meic Stephens has been added to the GCSE syllabus in Wales. The series has also inspired radio dramas, stage plays, art exhibitions and much political and cultural commentary. The Library of Wales 1 to 50 series was edited by Professor Dai Smith and published by Parthian.

Each book included an introduction giving us an opportunity to reconsider the series through an enthusiast’s eyes.

Dat’s Love and Other Stories by Leonora Brito is No 47.

*

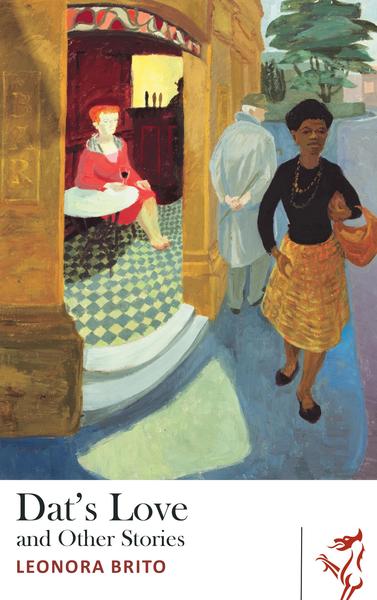

Leonora Brito was a writer of exceptional stories. Her professional creative life covered a relatively short period of time, from the early 1990s to her death in death in 2007, during which she produced an acclaimed collection of short fiction, Dat’s Love, in addition to writing for radio and television. She was the first winner of the Rhys Davies short story competition and contributed the title story to ground-breaking anthology Mama’s Baby (Papa’s Maybe) which also saw the publication of Rachel Trezise’s first story. Brito was an editor of Trezise’s first book, In and Out of the Goldfishbowl. The cover painting is entitled Warm and Cool and is a depiction of street life in Tiger Bay in the 50s by influential artist and teacher Joan Baker. This world moving from the 50s through to the 80s is captured eloquently by Brito who was working on a second collection at the time of her death, aged fifty-three.

The book is introduced by Francesca Rhydderch who published some of Brito’s work while she was editor at the New Welsh Review. Rhydderch’s first novel is The Rice Paper Diaries which won the Wales Book of the Year Fiction Award in 2014.

“Leonora Brito… was a writer who knew herself, knew her worth, and knew that it was the work itself that mattered, the characters and stories whose voices she threw so brilliantly on the page.”

Francesca Rhydderch

Dat’s Love, first released by Seren in 1995 and now re-issued by Parthian in the Library of Wales series accompanied by two additional stories, was the single collection published by the exceptionally talented Leonora Brito. Some of these short fictions were broadcast on Radio 4, and the title-story, which won the Rhys Davies Short Story Award in 1991, was also anthologised by Susan Hill in The Penguin Book of Contemporary Women’s Short Stories. At the time of her death in 2007, Brito was working towards another collection of stories.

Leonora Brito was born in Tiger Bay, Cardiff, on July 7 1954. Her mother and grandmother were from Cardiff, while her mother’s father and her own father were seamen from the Cape Verde Islands. Many of Leonora’s stories hark back to the people and places of an earlier generation. ‘Dat’s Love’, one of her most popular and enduring pieces, about an aspiring young singer who works in a cigar factory, is typical in this respect, bringing together two of Leonora’s central concerns: music, which blares powerfully at the reader from the first line of the story (‘Dat’s love, tra la, la, la, dat’s love’), and the interior monologue of a young working-class black woman on the cusp of adulthood. The Cardiff Leonora wrote about was her grandmother’s Cardiff: the Docks, Butetown, Tiger Bay – local ground which she recalled in her memoir-essay ‘Staying Power’ as ‘not […] the dangerously exotic, nefarious and essentially fictional place so often conjured up by (mainly) male writers for popular consumption’. For Brito, this was ‘an altogether more mundane spot that resembled if anything a friendly, spiteful, gossipy, yet neighbourly, village’.

Leonora Brito was born in Tiger Bay, Cardiff, on July 7 1954. Her mother and grandmother were from Cardiff, while her mother’s father and her own father were seamen from the Cape Verde Islands. Many of Leonora’s stories hark back to the people and places of an earlier generation. ‘Dat’s Love’, one of her most popular and enduring pieces, about an aspiring young singer who works in a cigar factory, is typical in this respect, bringing together two of Leonora’s central concerns: music, which blares powerfully at the reader from the first line of the story (‘Dat’s love, tra la, la, la, dat’s love’), and the interior monologue of a young working-class black woman on the cusp of adulthood. The Cardiff Leonora wrote about was her grandmother’s Cardiff: the Docks, Butetown, Tiger Bay – local ground which she recalled in her memoir-essay ‘Staying Power’ as ‘not […] the dangerously exotic, nefarious and essentially fictional place so often conjured up by (mainly) male writers for popular consumption’. For Brito, this was ‘an altogether more mundane spot that resembled if anything a friendly, spiteful, gossipy, yet neighbourly, village’.

It was in this ‘village’ that Brito was born, in the family’s two-room lodgings on Christina Street. The house was shared with the family’s Malayan landlord, Kaddi, and ‘another young family, headed by a seafarer named Limbo who practised becoming a jazz trombonist in between trips’. Leonora, or Lee, as she was known to her family, was the eldest of six. Soon after her younger sister Rose was born in 1958, the growing family put their belongings on the back of a van and left Tiger Bay, along with many other families who were being moved out to the new housing estate at Llanrumney: ‘I’d just turned five on the bright summery day we left the Docks,’ Brito later wrote. ‘I don’t remember any tears, only a mood of excitement and adventure as my brother and I were hoisted onto the back of Billy Douglas’s open lorry and deposited in the family armchairs, one apiece.’ Her short story ‘Gone for a Song’ is a resonant account of life on an estate similar to the one in Llanrumney, hinting at a mother’s possible infidelity while the father is away. Like ‘Dat’s Love’, it is a story that begins with music, followed by images exploding with vivid colours, all narrated in a strong first-person present tense voice: ‘It’s white lime it is, he’s throwing,’ a young girl says of her next-door neighbour, who is singing the tune to ‘Only the Lonely’ to himself as he walks up and down the garden scattering the lime over a hitherto neglected patch of earth. ‘And it stays on top of the brown soil where he’s dug it over, like icing sugar on a wedding cake, white.’

In an interview with Brito in 2003, fellow writer Charlotte Williams drew attention to another moment in the same story, when the narrator sees a herd of cattle in the field next to the estate – ‘fifteen Africas painted in ink on their creamy white backs, like maps’. Williams wondered if this inscription of ‘not only black but Africa’ on the Welsh countryside was a conscious statement. ‘Is the Welsh landscape part of you?’ she asked. Brito’s reply was both honest and laconic: ‘“Gone for a Song” is situated in a kind of borderland between the city proper and the countryside. The actual locality is the Llanrumney housing estate. We were black and we lived there, as did lots of other black families, so I was simply describing that. The Welsh landscape doesn’t loom large in my idea of myself.’

Although she was quick to avoid mythologizing or romanticizing the places where she lived in Cardiff, Brito admitted that Tiger Bay, the ‘village’ where she had been born, was even then beginning to exert a strong personal and creative pull on her: ‘As kids going about our daily business we were subjected to constant casual name-calling from other kids, what is now termed racial abuse,’ she wrote in ‘Staying Power’. ‘We learned to hit back, but by the time I reached junior school I began to harbour a secret dream of one day returning to live down the Docks, where life would be miraculously happy and uncomplicated.’

While the family continued to frequent Tiger Bay to see their relatives, they didn’t live there again. Instead, they moved closer to the centre of Cardiff, to Cathays, where Leonora attended St Cadoc’s Roman Catholic Primary School, followed by Lady Mary’s Secondary Modern. It was becoming clear to her parents that she was a bookish, creative child who loved writing and painting, and was doing well at school. Her mother went to see the headmaster of Lady Mary’s to make a timid request for Leonora to be moved over to a grammar school, but according to Leonora’s sister Rose she was met with a flat refusal.

When Brito left school at sixteen, she took various office jobs, and it wasn’t until she was twenty-one that she enrolled at art college to do a foundation course. None of Leonora’s artworks has survived, but the vivid, almost cinematic quality in her writing surely owes something to her training in Fine Art, and it would have been fascinating to explore the cross-fertilization between her paintings and stories. In ‘Stripe by Stripe’, for example, Brito sketches a scene with just a few bold strokes: ‘At around about half-past five, two black boys crossed over the back yard of the maisonettes and headed towards the pub. It had been a very hot day, the sky was still a hazy blue, but the boys were dressed for evening, in black jackets and trousers, frilled white shirts and black bow-ties. From the veranda, Mrs Offiah watched them go. Like a double act, the boys ducked their marcelled heads beneath the empty washing lines, once, twice, three times, then straightening up together they leapt, high over the trampled-down part of the wire netting, and disappeared around the side of the “Blue Bayou”.’

When Brito graduated and returned to her office work, it was as a writer, and not an artist, that she persisted with her creative endeavours. In her mid-twenties, she changed direction again, to follow a degree in Law and History. Professor Dai Smith, editor of this series, taught her at Cardiff University, and his memories of her are one of the few glimpses we have of Leonora at this time in her life: ‘Leonora Brito took a third-year course I taught in the early 1980s at Cardiff University on Culture and Society in Britain from 1880 to 1920. In these classes she was painfully shy, either resolutely silent when others intervened or herself monosyllabic in reply, almost aggressive in her assumed diffidence. I struggled to engage her, to get to know her, and began to wonder if this Joint Honours Law and History student had stumbled onto my maverick course by mistake. Then she submitted an essay on Tess of the d’Urbervilles. It was a revelation – insightful, objectively researched, brilliantly executed in argument and delivery. She took no obvious delight in her First Class mark for it or my unstinting praise. In her Finals, she had a very mixed bag of results. The Law was not for her. Nor yet the desiccation of historical scholarship. But she was clearly the real deal. A writer.’

Brito was unemployed for a year or so after that, and although she was naturally a solitary person who lived alone and enjoyed her own company, there was, it seems to me, in this period of her life an element of her own portrayal of a young woman living with her parents in ‘Michael Miles Has Teeth Like a Broken-down Picket Fence’. What makes this visual, visceral story so powerful is the dislocating angst that permeates the ending, when news comes through that Kennedy has been shot. The narrator’s mother and father are deflated because the film they had been planning on watching isn’t going to be broadcast now, and they don’t quite know what to do with their evening. The final scene has a scarred, existential loneliness to it that stays with the reader: ‘Her mother raked what was left of the fire with the poker and asked Lesley-Ann to bring her the teapot from the kitchen. Then, her mother stood by the grate, one hand on the small of her back as if she was tired, and poured. A terrible hissing noise rose up from the cinders, and specks of ash flew from the fireplace and around the room. Lesley-Ann flailed her arms in front of her face like a wild thing, fighting off the ash, but her parents stood quite calmly, waiting for the air to clear.’ In a collection from which legions of strong, loud, exuberant voices reverberate off the page, this is a moment that, when the hissing of the cinders has faded, is unusual for its silence.

Despite the strong sense of place in Brito’s stories, there are several pieces in Dat’s Love which show her expanding beyond the square mile of her home turf. Her historical short fiction ‘Dido Elizabeth Belle – A Narrative of Her Life (Extant)’ is an examination of the British Empire in miniature, explored through the character of the illegitimate daughter of a female African slave and her English master, one Sir John Lindsay. ‘In Very Pleasant Surroundings’ is an example of a quite different piece, in which Brito pushes out beyond the boundaries of naturalism: this story of a woman’s final days in a hospice wraps itself around its central character in the form of scraps and snatches of literary quotations, reminding the reader that the short story is a construction of reality as well as a representation of it.

Although Brito was a little suspicious of what she thought of as the literary establishment, she was rightly proud of her achievement as a Rhys Davies prize-winner, and this moment of validation in 1991 was a turning-point for her. She gave up her job with the Welsh Water Board and embarked on a career as a full-time writer, which she combined with occasional freelance work as an editor and scriptwriter. Dat’s Love was published by Seren in 1995, who commissioned a second collection from her. Rose remembers how much happier her sister was once she was able to devote herself to her writing, and although Leonora died before the collection could be completed, on June 14 2007, some of the stories that would have gone into it were published in magazines and anthologies. Two of these, ‘Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe’ and ‘Jumpshot’, are included in this Library of Wales volume.

Some might think it sad that Leonora Brito didn’t enjoy greater acclaim during her lifetime, but she was a writer who knew herself, knew her worth, and knew that it was the work itself that mattered, the characters and stories whose voices she threw so brilliantly on the page. What matters now is the need to keep those voices alive.

Thanks to Rose Purchase, née Brito, Leonora’s sister and literary executor, for sharing her memories of Leonora with me, and to Professor Dai Smith for recalling her days as a student. Other biographical material is taken from ‘Staying Power’ by Leonora Brito in Cardiff Central: Ten Writers Return to the Welsh Capital (ed. Francesca Rhydderch, Gomer, 2003), and New Welsh Review 62, Winter 2003, ‘From Llandudno to Llanrumney: Inscribing the Nation’.

Leonora Brito was born in1954. Her mother was from Cardiff’s docklands and her father was a seaman from the Cape Verde Islands. Brito left school at sixteen, and it was until she was in her twenties that she attended college, taking a degree in law and history at Cardiff University. Her story ‘Dat’s Love’ won her the 1991 Rhys Davies Short Story Competition. She also wrote for radio and television, providing a unique insight into Afro-Caribbean Welsh society, largely unrepresented in Welsh writing until her work appeared. She published one collection of stories, Dat’s Love, in 1996. She died in 2007.

You might also like…

Former editor of New Welsh Review, Francesca Rhydderch‘s widely-published short stories have been broadcast on BBC Radio 4 and Radio Wales. In 2015, she was shortlisted for the BBC Short Story Award, a year after her début novel, The Rice Paper Diaries, won the Wales Book of the Year Fiction Prize. Today, Rhydderch gives us an inside peak into her writing space.

Francesca Rhydderch is also a contributor to Wales Arts Review.