Peter Lord reflects on the significance of Parthian’s republication of Miner’s Day by B.L. Coombes with Rhondda Images from Isabel Alexander and edited with an introduction by Peter Wakelin.

Miner’s Day was the last full-length book written by the collier Bert Coombes to be published. Unlike These Poor Hands, which had emerged in 1939 and sold fifty-thousand copies in its first year, it was not a popular success. Despite the fact that it was written as a commission from Penguin Books and given the additional status of issue in the ‘Penguin Special’ series, the new Parthian edition is the first since that initial publication of 1945. In his introduction, Peter Wakelin suggests that ‘the moment for Miner’s Day perhaps had passed. Since the 1930s a succession of books, photo essays and documentaries had made the coalfield less opaque to the rest of the country than it had been before.’ If so, one might argue that the author’s own ambition, expressed in an unpublished autobiography, to ‘do something to let the world know more about our way of life’ had been fulfilled.

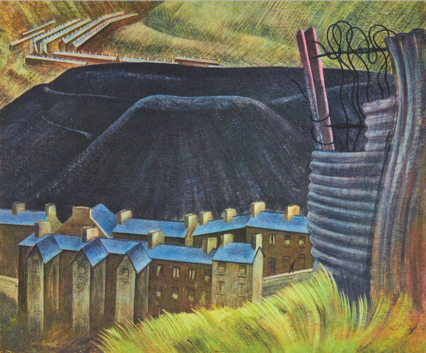

However, an unfortunate side effect of the relative obscurity of the book has been that its visual content has also gone largely unnoticed, along with the artist who produced it. Penguin had commissioned the painter Isabel Alexander to make a group of nine illustrations to Coombes’ text. By reproducing not only the original artwork, but also other portraits and landscapes made by Alexander on visits to the south Wales coalfield during the Second World War, this omission is now rectified. The Parthian edition combines the original text, Wakelin’s introduction and extended picture captions, and over seventy of Alexander’s drawings, elegantly assembled by the book’s designer, Olwen Fowler.

The precise details of how Alexander was chosen to illustrate Miner’s Day are unclear, but the painter had begun to work in the Rhondda before she met Coombes, and she was well connected in left-wing artistic circles in London. After training at Birmingham and at the Slade, she had taught at a secondary school before marrying the film-maker Donald Alexander in 1939. Alexander had been responsible for shooting the powerful film sequence of colliers scrambling to collect coal on a waste tip, with the wind scouring the dust around them, that was included in the celebrated Today We Live in 1937, and he had gone on to direct Eastern Valley. The marriage lasted only two years, but Paul Rotha, who had produced Today We Live, helped to support the painter and it was he who suggested that she travel to the Rhondda to work. By that time, it was a well-trodden path, frequented not only by film-makers but by photographers, who included Edith Tudor-Hart and Bill Brandt, and by painters such as Maurice Sochachewsky. Like Coombes himself, all were motivated by the desire to make known to the public their concern about the dire social crisis that had developed in the coalfield. Nevertheless, most of the visitors were transitory, including Alexander. After the war she did not return to Wales, and although other examples of her coalfield work were published in 1946, she retained most of her original drawings and paintings, and they were rarely seen in public.

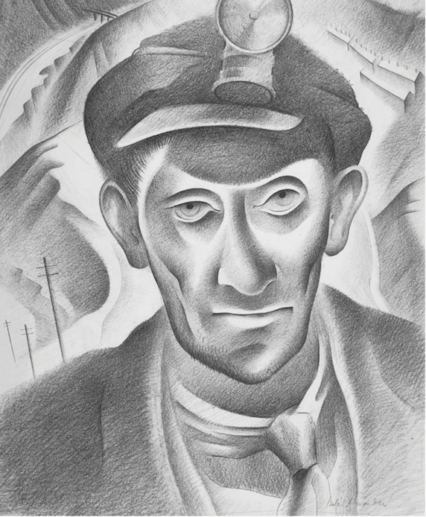

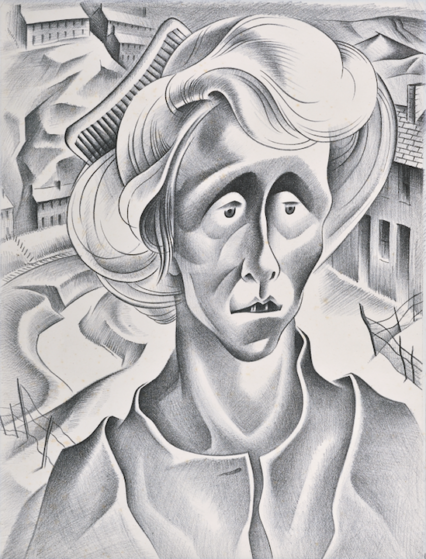

The brief attention paid to the mining community by these artists was not universally welcomed by those on the inside. The opening interviewee quoted in 1937 by James Hanley in his documentary text Grey Children felt that ‘We’re about fed up with people coming down here, looking us over as though we were animals in a zoo.’ His comments alert us to the exoticism that, perhaps inevitably, was an element in the perception of the outsiders who visited in the 1930s – a group largely remote from what they observed by reason both of their nationality and their social class. This element of exoticism had been present from the time of the Romantics, who had visited the industrialising Wales of the early nineteenth century, and was closely related to the ethnic alienation presented in the contemporary drawings and photographs of indigenous peoples in the colonised world. Especially evident in the portraits that dominate her Welsh works, it was a tendency from which Alexander’s images were not exempt. Stylistic intrusion between subject and painter was also immediately evident, reflecting a range of modernist influences on her work. The extent of this intrusion varied, but the images developed for reproduction, although monochrome, bear the marks of thorough, self-conscious, picture-making. Tokenistic elements – an oblique row of terraced houses, winding gear, triangular tips – float in surreal focus around the subjects’ heads, emphasising the bleak narrative, and unexpectedly recall the mythic fantasies of David Jones. In general, the original portrait drawings, executed in pencil or conté crayon, were more direct but, even there, Alexander’s sitters were almost always depicted as psychologically isolated individuals. Unlike the comparable but more social drawings that Sochachewsky had made just a few years earlier, there is little sense in her pictures of community, or even of family.

The result of this approach was not the picturesque deprivation found in the sentimental work of such Victorian artists as Dorothy Tennant. Nevertheless, in mood, Alexander’s portraits are one-dimensional. Almost without exception, they present a predominant sense of individual resignation, reminiscent of Millet, without a trace of the energetic politicisation and the internal contention that arose as a consequence, which were features of the community even in war-time. Notwithstanding the left-wing convictions that most of them held, it is curious that so few of the creative writers and the painters of the period brought that politicisation explicitly to the fore. Indeed, Joseph Herman, arriving in Wales in 1944, at the same time as Alexander was drawing in the Rhondda, observed of politics among those he drew at Ystradgynlais that ‘whether there was a strike or not, it didn’t worry me. I couldn’t be less interested.’ Insiders – Lewis Jones in literature, for instance, and Evan Walters in some of his paintings – took a different view, but this essential characteristic of the period is conspicuous by its absence in the work of Isabel Alexander. By contrast, Bert Coombes’ text, in its prosaic rather than poetic way, presented a more rounded perception of the period.

The result of this approach was not the picturesque deprivation found in the sentimental work of such Victorian artists as Dorothy Tennant. Nevertheless, in mood, Alexander’s portraits are one-dimensional. Almost without exception, they present a predominant sense of individual resignation, reminiscent of Millet, without a trace of the energetic politicisation and the internal contention that arose as a consequence, which were features of the community even in war-time. Notwithstanding the left-wing convictions that most of them held, it is curious that so few of the creative writers and the painters of the period brought that politicisation explicitly to the fore. Indeed, Joseph Herman, arriving in Wales in 1944, at the same time as Alexander was drawing in the Rhondda, observed of politics among those he drew at Ystradgynlais that ‘whether there was a strike or not, it didn’t worry me. I couldn’t be less interested.’ Insiders – Lewis Jones in literature, for instance, and Evan Walters in some of his paintings – took a different view, but this essential characteristic of the period is conspicuous by its absence in the work of Isabel Alexander. By contrast, Bert Coombes’ text, in its prosaic rather than poetic way, presented a more rounded perception of the period.

This observation is not intended as a negative criticism of Alexander’s work, though it does remind us of the potential danger of considering it as meeting the aspiration, implicit in the ambition of many in the period, to reveal social realities through objectivity or dispassionate documentation. The images of Isabel Alexander have the overriding and lasting virtue of individual vision. The republication of Miner’s Day in the wider context of her presentation to the world of individuals scarred by hardship and deprivation is an important and beautifully presented venture.

Miner’s Day is available via Parthian Books.