Bethan Hall caught up with fine art photographer Peter Britton – a photography lecturer for Coleg Gwent and Cardiff MET – to hear about his investigation into the Newton Burrows and Merthyr Mawr dunes ecosystem in South Wales, a visual and poetic project entitled S A N D.

Bethan Hall: Your recent project, S A N D, documents your photographic exploration of the Newton Burrows and Merthyr Mawr dunes area. What motivated you to embark on this project? Have you always been aware of the history in that area?

Peter Britton: This project has been a revelation of practice, experimental processes and total engagement with an environment and landscape. I decided to focus on this unique place as human engagement in a landscape, place and memory have become my underlying themes and areas of interest. With a working title of ‘These are my dunes’, I decided to photograph the local environment to capture the diverse history, landscape and stories of the dunes.

From an early age, the sandy trails at Merthyr Mawr Warren in South Wales have been my playground. Sunset walks with my father, spotting rabbits as they dashed into the brambles. Adventures with friends, making fires and building dens. Pellet gun wars, hiding in the disused rifle ranges. Beach parties, drinking MD 20/20 and collecting glow worms in jars. Mountain biking on the singed soil, after a summer blaze burned the bracken to cinders. The dunes have always been with me, as such the rich history has been part of my upbringing. The work collected through this project centres around this unique ecosystem.

Bethan Hall: The project involves an array of techniques and there’s a lot of content, covering the grasslands, saltmarsh, beach and woods. How long did it take you to put it all together? You mention in your writing that the landscape can change suddenly and dramatically — did that cause any continuity issues for you along the way?

Peter Britton: S A N D is the culmination of just sixteen weeks of investigation. I had extensive knowledge of the geography of the landscape, so I was able to meticulously plan and structure the project across all of the areas of investigation. The unique ecosystem covers nearly one thousand acres and is incredibly diverse in terms of landscape and human history. Working across winter, spring and summer, the habitat changed almost on a daily basis and allowed for adaptation of photographic processes and methods. I worked with the seasons and weather to show the diversity of the environment.

Bethan Hall: It seems that the project required a lot of research; your work is not only showcasing the environment, but also teaching people about the area’s history and landscape. What did you find most interesting or surprising?

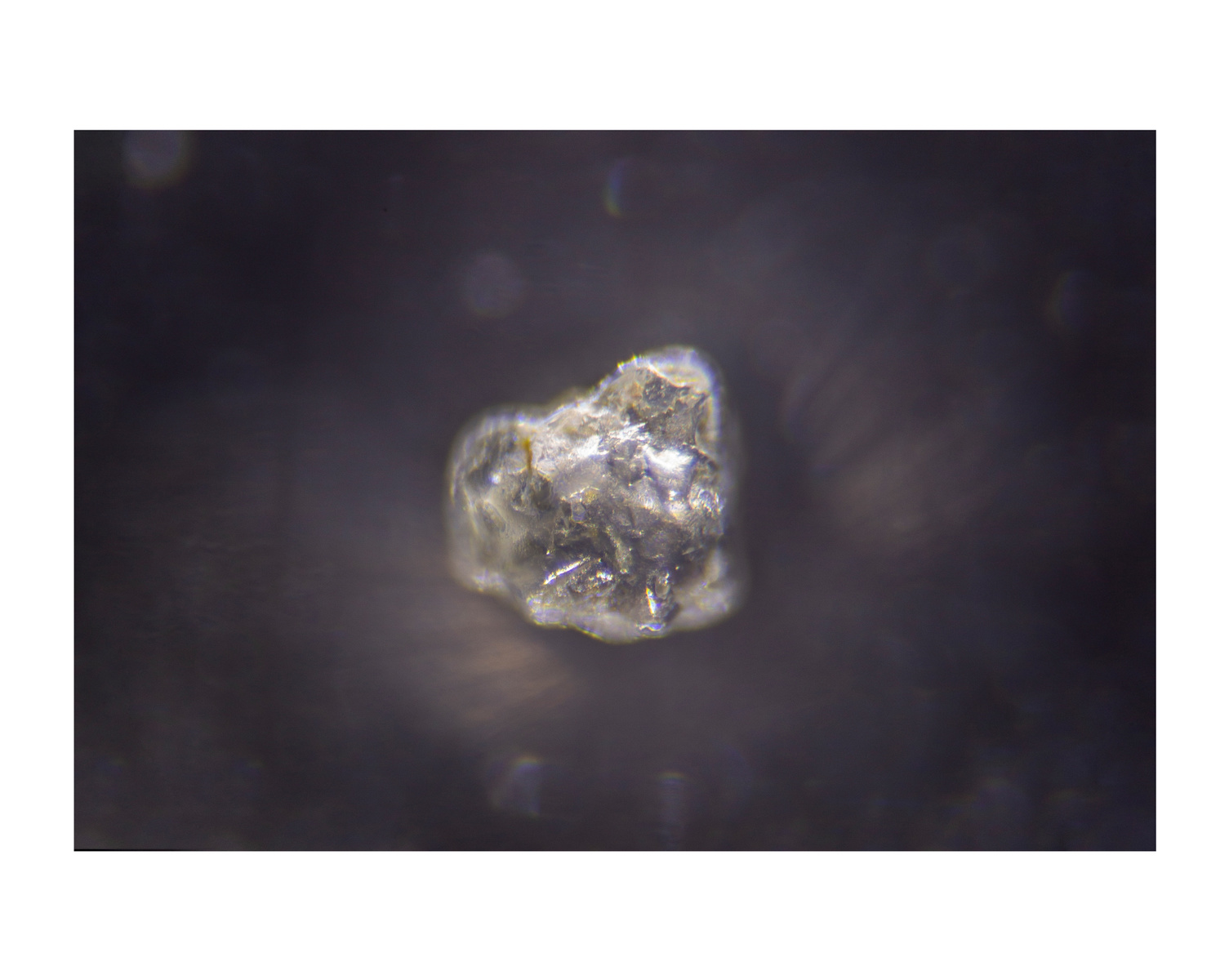

Peter Britton: During the early stages of the project I realised that sand was a binding element within all of my pictures and experiments. Hence the name. The multiplicity of purpose and the multi perspectives of the dunes are also important issues within the work. The crossover, correlation and link between ecosystem and human use is hugely important within this project. The dunes have many purposes and that was an aim of photographing these different areas of interest. But the most eye opening and fascinating investigation was possibly one of the smallest. I decided that as all of the project areas were linked by sand, sand should be investigated. I read a wonderful book (called, unsurprisingly, Sand) by Michael Welland that offered an insight into the importance of this microscopic material upon our world. Via that research, I photographed sand in three ways: within the landscape, on a macro scale and on a micro scale. These are my three favourite images from the project as the macro and micro images reveal the true beauty of a single grain of sand. You can see these images under the title ‘Let my bones turn to sand’. The most wonderful fact that I gleaned from my research is that our universe contains at least seventy septillion stars. Astronomers estimate there exist roughly ten thousand stars for each grain of sand on Earth. When we stand on the beach, the consideration of this fact is enormous.

Bethan Hall: I also wanted to ask about the poetic aspect of your work. The sections have creative titles and ‘These are my dunes’ is framed by a short poem. What inspired you to take this poetic approach? Did it feel important to the project overall?

Peter Britton: The poetic approach within the work is of utmost importance as the area of landscape that I was investigating was incredibly personal for me. I photographed in a variety of ways: whilst walking, whilst with my children and occasionally I would even take a camera on a run with me over the dunes. I use the dunes for recreation, escape and wellbeing, and this translated into both the themes of the project and the resulting text.

Bethan Hall: I was intrigued by ‘The vast and seamless sea’, ‘The hillside bracken shines like the river’ and ‘The wind whips’, which you refer to as images made by the land. Can you tell us more about how you created these pieces?

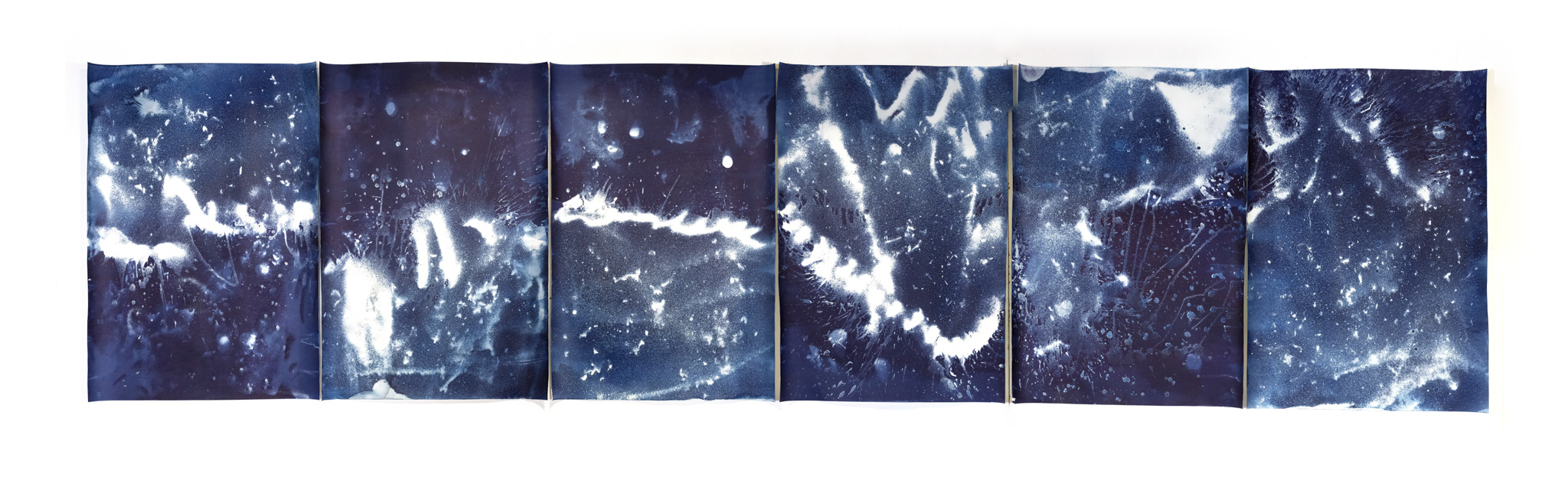

Peter Britton: Andy Goldsworthy, a British sculptor who creates temporary landscape art installations was the main source of inspiration. Much of Goldsworthy’s land art is ephemeral, and is a comment on the Earth’s fragility. I connected with this as many of my experiments in this module have centred around using the landscape to create certain pieces. Meghan Riepenhoff was also a great influence. Her method of immersing cyanotype imbued paper in waves as they break is such an amazing way of using the landscape to create a photographic representation of a moment. The action of taking a picture disperses all sensation whilst being in the moment of a landscape; all senses are lost, even vision, as we create a 2D representation of the 3D world around us. Riepenhoff’s style of photographic creation, where the landscape makes the art, is a wonderful way of making an artistic piece into a sensuous experience. Riepenhoff’s work led me to several ideas, all based around allowing the landscape to make the imagery. These images are ‘landart’.

In ‘The vast and seamless sea’, I use the cyanotype process to create the imagery. These cyanotypes represent a single crashing wave as it breaks on photographic paper, washing sand and salt water over the surface. The resulting multi-layered textural image is a representation of a single wave breaking on Newton beach. The work made for ‘Hillside Bracken’ was possibly one of the most rewarding to make. The pieces were created by painting cyanotype solution onto heavyweight watercolour paper which was then left at the dunes over a period of twenty-four hours. Over that period, the surface of the paper was exposed to rain, hail, sun and frost. The pieces were found and collected, then returned to the dunes for a further twenty-four hours where they were re-soaked and ‘inked’ to allow the wind and rain to form pattern and shape. The resulting images are formed by sun, rain, wind and hail; imagery made by sand, bracken, leaves and soil. ‘The Wind Whips’ is a collection of images that represent where water meets land. Made using cyanotype offcuts and pigment inks submerged in a tray on the seashore in water from the Bristol Channel, these images have been created by the sea and the landscape. The ever-changing position of the sea landing on the beach allows for a continuous evolution of the shape and sensation that our beaches offer. Never the same, but always familiar.

Bethan Hall: I suppose letting nature shape your work like this could be perceived as a reflection of the way humans have shaped the landscape of the area. Does it seem this way to you, or do you read it differently?

Peter Britton: A landscape is a collection of interactions and stories. Humans have helped shape the landscape, but one theme that the project has is memory. The relationship between place, memory and photography is multifaceted. The very nature of photographic visual recording means that as one records, one creates ‘memory’ both via the medium used (on film or a memory card) and through the act of being present, of being in that moment (the memory imprinted on one’s mind). These memories that are created allow us to develop an awareness of ‘place’. Through one’s imagination, and via the capture of imagery, it is possible to create narrative and fantasy that sits comfortably within one’s own sphere of consciousness. This has always been the case with the dunes. Wandering thoughts, hopes of love, dreams of success and, in earlier days, childhood games were an integral part of building confidence and aspirations. By allowing our minds to wander, we generate ideas and give ourselves the potential to resolve and make better. A thought imagined whilst within a landscape, in nature, outdoors, with the elements on our skin, is a thought not of the present, but of the future. It is a thought of becoming. That makes the landscape the catalyst; the giver to be released into the ever-flowing waters of evolving time.

Bethan Hall: Would you say there is any sort of ecological motivation behind the project? What do you hope people will take from it?

Peter Britton: There is certainly a focus on conservation and ecology within the project. The dunes landscape is one of constant change, and it is a vulnerable landscape because of the sand on which it is formed. There is a wealth of rare species of flora and fauna over the dunes, and the ecology and co-existing plants, insects and animals are vital to the stability of this environment. Tourism is an integral and important part of the dunes. Situated at the end of Porthcawl (a tourist town in South Wales), Newton Beach is a haven for holidaymakers. Locals and those travelling from afar enjoy its sandy shores and crashing waves and it is the ideal playground to put toes in the sand, but this can have a detrimental effect upon any landscape; a balance which allows for natural erosion without the conflict of human impact needs to be maintained.

Bethan Hall: Do you have any more projects lined up at the moment which you can tell us about?

Peter Britton: I currently have two ongoing projects.

The first is called ‘Ghost ships and tides’ and is an investigation into Tusker Rock. The project’s intentions are to create a legacy for the lives of those who died as a result of being shipwrecked by the rock. I have photographed and filmed the rock and the wreck remnants via both film and digital processes (5×4 large format photography, DSLR and Drone), and I intend to create installation pieces using gelatine glass cyanotypes. This is working towards an exhibition/installation comprised of sea glass cyan abstractions (circular glass layers gelatine cyan printed with the surface of the sea through which the viewer can observe the shipwrecks [drone shots] below), printed large format imagery, a moving image piece and an accompanying sound installation.

The second is entitled either ‘The Sun Ablaze’ or ‘The Sun of a New Day’, and this is a visual, photographic and artistic interpretation of National Trust locations across Wales. Overall, the project will be about the diversity of the Welsh landscape, the history of each of the NT sites, topographic variety, and the range of different plant specimens across Wales. Using the camera-less photographic process of cyanotype combined with poured acrylic art, I am producing a piece of art for each of the fifty plus National Trust venues across Wales, starting with six locations to test the project.

You can find out more about S A N D from Peter Britton here.