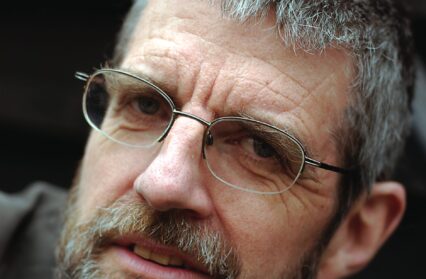

In the latest of a new series of Q&A’s with some of Wales’s leading artists, musicians, performers, and writers, award-winning poet Philip Gross discusses the influence of origins and the “essential nutrient” of collaboration.

Where are you from and how does it influence your work?

Ah, ‘from’… That word begs a lot of questions. Born in Delabole, North Cornwall… Brought up in Plymouth… 20 years bringing up a family in Bristol… 20 years since, in a different life in South Wales. Each feels like a species of ‘from’ to me – as does Estonia, my father‘s homeland. Visiting there, finding family, making friends, backfills another kind of ‘from’. All of those places are a part of me, so part of my writing too, as is the fact that they are several, shifting, not to be taken for granted.

Where are you while you answer these questions, what can you see when you look up from the page/screen?

Ironically, in transit – to poetry event in Manchester. I began this answer in a crowded station café, during a long delay…. and continued it, in motion – right now with a white froth of trackside hawthorn bushes going by. Unkempt, irrepressible stuff, I love it. And I’m typing it up now, another now, at my desk, in Penarth. Looking up, I see a painted stone, a mini-memorial to my father, on loan from Scottish artist Peter White as part of his concern for refugees.

What motivates you to create?

What motivates any of us to look, to be curious, to think? Take that, add a good luck of being alive in language that’s able to give these things tangible form – and look, it’s creativity. Or you could just say, it’s what I do, how I touch the world, how I find out what I’m thinking. Who wouldn’t do that? The extra step of wanting to share, to be part of a poetry culture, that’s a different answer, but related. If we want a living medium to think in, it needs to exist in some kind of conversation, whether you yourself publish or not.

What are you currently working on?

It’s not so much ‘what am I working on?’ as ‘what seems to be working on me?’ Writing the poems, helping them coalesce from the glorious mess of my notebooks, helps answer that. And the books, which might sometimes look like explorations of a subject planned in advance, are the next stage in that coalescing: spotting patterns forming, relationships between this and that. You have to trust it, even when it’s by no means clear where it wants to become.

When do you work?

Between times. Or maybe: slightly all the time. It’s easy to say that, I know, as a poet. When I’ve been writing novels in the past, regular working hours are essential. I can do it… Only I keep on glancing away and I look back half an hour later to find a written a poem instead. I know, I’m lucky to have the freedom to answer like this, but it wouldn’t have been much different in earlier, more 9-to-5-ish stages of my working life. In periods when I’ve been ‘too busy to write’, it was poetry that found a way to happen anyway.

How important is collaboration to you?

An essential nutrient. Each good collaboration with artists, writers or whatever art form, has been a source of new energy and fine surprises – being surprised what I find myself writing as well as what the other brings. Then again, I’ve come to suspect that all creative work is collaboration – sometimes with things I’ve read, seen, heard, years ago – or with places, with people I’ve never met, with passing eavesdropped voices in the street.

Who has had the biggest impact on your work?

See answer 6: the people with whom I’ve got into that state of trust and exploration that a living collaboration can bring. That, more so than poetry groups, though I’ve been grateful to some chance workshop relationships at key moments in the past. Workshopping is a process I believe can be extraordinarily good, a model for human relating, but only with a careful, thoughtful holding – at worst, it can be bland, it can be crushing. Much of my teaching life has been to do with that. Some writing friends have seeped into my bloodstream naturally. I’ve never fancied being a member of a literary style camp or faction. Finding myself ‘located’ like that, my instinct is to walk the other way. (Or so I like think. An acute observer might know better.)

How would you describe your oeuvre?

I wince a little at the word oeuvre, but fair enough, it does feel like an organism, a whole thing, even though it’s looked varied on the surface, with the children’s writing, radio and stage work, as well as the poetry. That doesn’t mean that I know what the organism is evolving into. Rather, let’s say it’s a kind of landscape that has been creating itself as I’ve moved through it. There’s nowhere I can stand to see whole. Nor do I want to. It’s the journey, the journey-ing, that is the life of it. The moment I know what it adds up to, well, then, presumably it’s done.

What was the first book you remember reading?

Janet and John Book 3, in the reading scheme schools used in the mid 1950s. I remember the thrill of being allowed to go on to real stories with titles of their own. Mind you, I seem to remember getting absorbed in my grandfather’s leather-bound encyclopaedia at match the same time. Was I reading? And I hear him reading Rudyard Kipling out loud (he’d been born and raised in India) with me peering over his shoulder.

What was the last book you read?

Orhan Pamuk’s The White Castle, which has been sitting on my shelves patiently. Five years on from releasing myself from teaching creative writing at the University of South Wales, I’m only now recovering the appetite to read books for their own sake. Oh, and I’m dog-paddling slowly through Marcel Proust. I knew the time would come eventually. I’m reading it at bedtime, to be lulled by the swirling currents of imponderable syntax.

Is there a painting/sculpture you struggle to turn away from?

That’s a very specific question, maybe one that presumes a particular way of relating to art. I think I respond to artists more than to this work or that. I could spend any amount of time among an exhibition or a book of paintings by Paul Klee, but I can’t resolve it to a single painting – that somehow wouldn’t be the point. I’ve been in exhibition spaces, quite recently, where I’ve physically found it hard to leave, a little pang like grief – among the tremendous enigmatic hanging fabric works by Magdalena Abakanovicz in Tate Modern, or in a James Turrell skyscape in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.

Who is the musical artist you know you can always return to?

Artist? I hope that can mean composer. Arvo Pärt, enduringly, for the spaciousness of his music, its way of suspending time. Many composers singers sometimes have a particular, circumstantial hold on me, or answer a specific need – but Pärt is the one that qualifies for ‘always’.

During the working process of your last work, in those quiet moments, who was closest to your thoughts?

Honestly… In almost all of my writing of the last 25 years, apart from those breathless to-and-fros of one or other collaboration, the answer is my wife Zélie, who’ll be somewhere in the house while I work, mostly not in the centre of my thoughts but all around them, co-creating the whole practical medium of living, of home, where the writing lives and breathes.

Do you believe in God?

I could stick with my first-ditch defence of saying ‘Tell me what do you mean by God and I’ll say whether I believe in it.’ To most of the possible answers, I’d say No. To the rest, I’d say ‘OK, but what do you mean by believe in‘? But I won’t. Let’s start again… I’ve been a Quaker, by choice, for a large part of my adult life. None of the reasons for that depend on ‘believing-in’. The plain, heartfelt, undogmatic language of Quakerism is one in which I can move in with ease, sometimes using the word God without being forced to unpick the layers of metaphor, of as-if, or of factual belief.

Do you believe in the power of art to change society?

Do I believe in the power of breathing to change society? Yes, in as far as people absorb it and are nourished by it – especially if the air is fresh and clean. Art, ditto: oxygen for the whole being. Campaigning art can be a weapon for any cause, good or bad, and it’s one we might need. But I suspect that the deeper changes art enables are the ones the artist isn’t doing consciously at all, registering subtle shifts around us and inside us that nobody, them included, is aware of yet.

Which artist working in your area, alive and working today, do you most admire and why?

Michael Longley – for holding a place of balance, sanity and quietness in the North of Ireland while being fully aware of the violence around him. I admire his ability to turn to the slow specific facts of landscape, nature and place, and to hold a perspective back to Classical literature, as a way of speaking to his times in non-partisan ways. Also for holding to his writing in the long haul even though, for years, it seemed to have deserted him.

What is your relationship with social media?

Feeling wearily compliant, and a bit coerced. That’s realistic: I accept that this is a change as fundamental as Gutenberg’s printing press, which both opened new channels of knowledge and unleashed centuries of crazy intolerant contention. I know that the print form and the small in-person reading I’m at home with will soon seem as quaint as illuminated parchment. Maybe as valuable, too.

What has been/is your greatest challenge as an artist?

That sounds heroic, Romantic, in a way I don’t associate with myself. But mainly, I guess, the challenge is to keep the faith. Faith, that is, in the way the poetry is leading – to trust that it matters – even in periods when the world isn’t coming back with much encouragement. And all the more so, maybe, in times when it is. I know the growing points for me are seldom in the place where a prize or shortlisting has told me Yes. Like that. Do it again.

Do you have any words of advice for your younger self?

Don’t be too afraid. (A bit of afraid is perfectly in order.) The things you’re worrying about won’t be as bad as you think. The real crises, for you and the world, will come from a direction you’re not looking. And trust, surprisingly, that poetry is one of the things that will see you through.

What does the future hold for you?

Well, clearly, the unlovely facts of old age. And yes, dying, my own and my loved ones’… though I hope not just yet. If writing is my way to be in conversation with what’s real to me, this must be part of it. That’s not a gloomy thought. Just as a poem is a thing with the shape in the air or on the page, I’d hate for my life not to have a shape in time. And I do believe that every point in the life-landscape has a perspective not available from anywhere else; the world needs them all, to see it whole. I like Edward Said’s thinking about artists, writers and musicians who take themselves apart, or are taken apart, by an unpredictable Late Style – though that mustn’t become a deliberate plan, or it’s fake. But… let’s see.

You can find out much more about Philip Gross’ writing on his website.

Philip Gross Philip Gross Philip Gross Philip Gross Philip Gross Philip Gross