Galeri Ten, Windsor Place, Cardiff

It’s a funny business, being a superhero. Not only are you expected to conquer the forces of evil, but you are also expected to conquer yourself, too. And you can only defeat the bad guy if you can overcome your own deep-rooted sense of hubris, which is something that is beyond the abilities of anyone connected to the dark arts.

If you think about it, this is what fuels almost every major Hollywood blockbuster. This sense of transformation, the overcoming of the self, has fuelled any number of cinema productions ever since George Lucas credited the writing of his Star Wars script to the influence of Joseph Campbell’s teachings on the Monomyth. In The Hero With A Thousand Faces, Campbell points out the universal stages a hero must go through in order to change from a human being to the demi-god capable of delivering a happy ending, something that Lucas found fitting for the transformation of a farmhand into a Jedi.

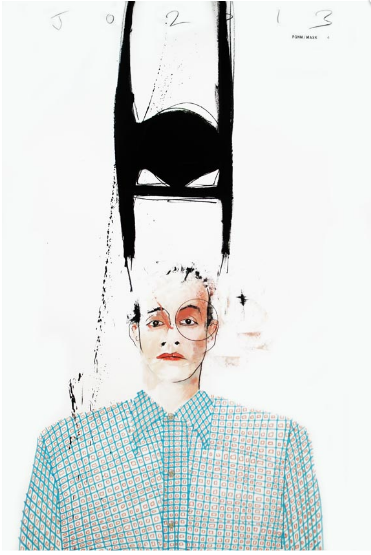

Jon Oakes shows signs of this influence in physiognomy, which is currently at gallery/ten on Windsor Place, Cardiff. Whilst the superheroes in his pictures are in disguise, it is the ordinariness in them that stands out. By giving his portrait figures masks, Oakes has succeeded in showing the hero in all of us, and how the superhero is essentially another human being. This notion of relating to the Superhero is an integral part of the mythical creation: they can fight the forces of evil but also have to battle and overcome the personal demons we all face.

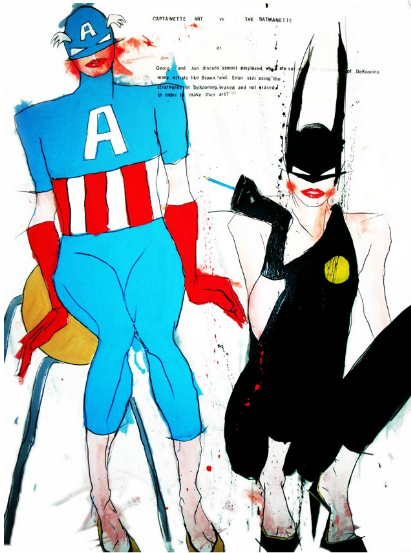

Picture Neo fighting the agents when he finally ‘gets’ The Matrix and realises he is The One. Think of Luke Skywalker turning off his target-locking on the Death Star’s fuel pipe when Obi-Wan’s voice tells him to trust himself and use the force. Try to cast aside the terribleness of Toby Maguire’s Spiderman while remembering the unmasking scene on the bridge, which endeared Peter Parker to the New York public, allowing him to remember he is not the villain and can fight the Green Goblin to the death with new-found confidence. In Oakes’s Mask series of pictures, this unmasking is taken literally, and the twinning of the human with the deistic raises a smile. But it is Oakes’s talent for subtly capturing an emotion on the face, which may only be present for a moment in time, which makes his pieces really stand out. In Mask 4, a Batman-style mask with triangle slits for eyes floats above a balding man, whose own wide open eyes look like they’re pleading for some type of understanding. Mask 7 shows a superhero with his hands in the air as if he is in the middle of the Haka, yet his coat could be straight from the back of Arkwright in Open All Hours. The playful humour works well here, especially when used with bold, bright colours, in catching the eye and holding its attention.

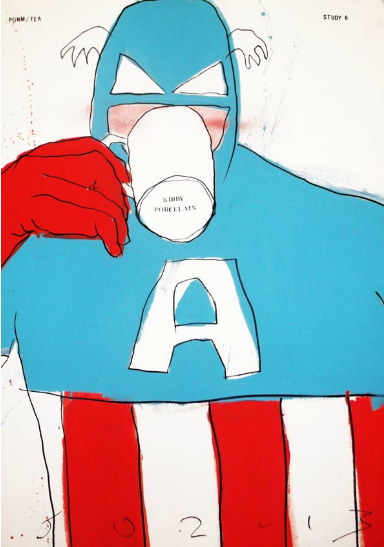

Having said that, this theme is not as successful in other places, such as his Spiderman and Captain America Tea pictures, which show the Superheroes drinking out of ceramic mugs made by their writers/illustrators (Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, and Jack Kirby respectively). While Oakes’s skill as a draughtsman is still evident and there is a delightful element of cheekiness in their raising of a mug of cha, there is something about a Superhero doing something so mundane that speaks of arrogance towards us mere mortals. It is not so much that they are one of us, but they are poking fun at our own mortal sense of being, through a very fake version of humility.

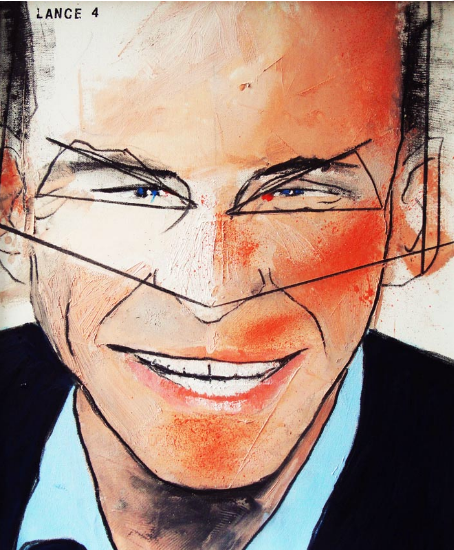

But it is not just the hero that Oakes depicts. He also does a great line on the anti-hero, too. In his Lance series of pictures, we are confronted with eight pictures of Lance Armstrong, the fallen superhero. The emotional range on these close-up portraits makes them look like they could have come directly from his now infamous confessional Oprah interview. In Lance 8, we find the drug cheat grinning like a chimp. In Lance 4, his face has the slightest sketch of a mask, which frames his eyes to bring out the sinister aspect of his face and character. By splashing on colourful paint, and then adding detail in broad black strokes, Oakes manages to balance both the immediate and the delicate in his work to great effect.