Phil Morris interviews Jonathan Edwards about his involvement in Velvet Coalmine and his collection of My Family and Other Superheroes.

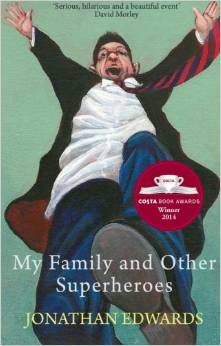

Jonathan Edwards was born in Newport and grew up in Crosskeys in the Gwent valleys. His first collection My Family and Other Superheroes won the Costa Book Award for Poetry in 2014 and the Wales Arts Review People’s Prize at the 2015 Welsh Book of the Year Awards. From September 1 – 6 the Velvet Coalmine arts festival takes place in Blackwood, featuring an eclectic programme of rock music, literature, theatre and debate. Ahead of Jonathan’s appearance at this year’s Poetry at Preachers event he spoke to Phil Morris about how his work is inspired by the people and values of Gwent.

Phil Morris: I suppose we should start with your involvement in Velvet Coalmine – how did that come about?

Jonathan Edwards: Last year, Iain Richards (Festival Director) invited me to take part in a Velvet Coalmine poetry event held at the Wetherspoons pub in Blackwood. Rhian Edwards was the headliner. I thought this is just brilliant – a local festival featuring local writers, musicians and artists. Clare Potter and Patrick Jones, who are reading at this year’s festival, are both from Blackwood, while I’m from Crosskeys just down the road. Velvet Coalmine also draws some amazing names, especially for the music stage – The Meat Puppets are playing this year.

I was reading at Latitude this summer, and a London performance poet, said something to me along the lines of: ‘My kids think that they live in the ghetto, and I say to them you’re not in the ghetto, just imagine yourself somewhere in the south Wales valleys where there’s nothing happening.’ So I think outside the valleys there is this perception that it’s a bit of a cultural wasteland, and a festival like Velvet Coalmine can be useful in challenging that perception because it showcases and celebrates the enormous amount of talent and the brilliant sense of humour you can find here.

Wetherspoons is an odd venue for a poetry reading; what was the atmosphere like?

I’ve done readings in all sorts of bizarre places this year, and I think it’s really good to take poetry out to people who wouldn’t necessarily read it. We do a monthly event at The Murenger in Newport, where we read our poems standing outside the toilets, which is great, because every now and again you have to stop so that someone can get past and go for a pee.

I bet W.H. Auden never had to do that.

No, he didn’t; but perhaps he should have.

I imagine that many in the audience in that Blackwood Wetherspoons would resemble the characters who appear in your poems, many of which you’ve observed at close quarters.

Yes, my writing is very observational, which is partly out of sheer laziness. Some days I don’t have anything to write about, so I look out through the window and write about what I see. That has been read as a kind of political decision, that I’m writing about people that poetry isn’t often written about or doesn’t often celebrate. I don’t know if my poems are ever entirely preconceived in that way, but I think you do inevitably write poems about people and things that you’re kind of emotionally engaged with, that you love and think are important. Do you know Tom Morris?

He happens to be a good friend of Wales Arts Review.

I was at his book launch on Saturday and he talked about the literary culture in Ireland, where it’s seen as totally natural that you write about where you are and your immediate surroundings. I think for me, ultimately, I write poems about what I love, which I suppose at some level is bound to be a kind of a political decision.

With your recent award-winning success have you been tempted to move away, to a big city, somewhere like London for instance?

No. And I wouldn’t do it anyway. I love this area. I love Newport and I love the valleys.

For me, it’s very much to do with the past, and my relationship to previous generations of my family. I live my life looking up at the same mountains where my great grandparents lived. That keeps me rooted. A lot of my ancestors are quite enigmatic and fascinating for me. I think in moving away I’d be cutting off roots to my past, which I wouldn’t want to do.

Your collection My Family and Other Superheroes isn’t focused on the geography, the landscape of the Gwent valleys. The focus is squarely on its people.

Absolutely. We’ve got these brilliant personalities here, haven’t we? We have a very unique identity that I think should be celebrated.

Is there such a thing as a Gwent identity that is distinct from a Welsh identity?

That’s an interesting question. ‘Devolved Voices’ in Aberystwyth do this series of video interviews with poets, and one of the questions they always ask is do you consider yourself to be Welsh. Claire Potter’s answer was something like, ‘I don’t consider myself a Welsh poet, but I consider myself a valleys poet’ – and I think that’s a brilliant answer. I mean, Wales is such a diffuse thing – there are so many different kinds of Wales, conceptually and even geographically.

At the same time, we all live in families and we all have grandfathers, and though we might not call them by the same word we all sort of feel the same way about them. I think sometimes, in trying to write about something local you accidentally write something that has a much wider appeal.

How would you characterise the people of this part of Wales, for those who are not from the Gwent valleys or Newport?

I think there’s a strong sense of caring for each other. I live in a community where if there’s one day when my Dad doesn’t walk up to the shop at a certain time to get the paper then about ten people will ask why. I like living in a place where an individual matters in that way.

And alongside your observations of people and themes, which are very specific to the valleys, there are these frequent pop-cultural references that look beyond that world, and to America in particular.

And alongside your observations of people and themes, which are very specific to the valleys, there are these frequent pop-cultural references that look beyond that world, and to America in particular.

American poets have been very influential on my work, particularly David Wojahn. He wrote this brilliant book called Mystery Train, which is a sequence of fifty sonnets. There’s one about the filming of Apocalypse Now and one about William Carlos Williams watching Elvis Presley on TV. Wojahn’s approach – that of taking ideas from what might be considered low culture and placing them in the literary context of a poem in a playful way – was really interesting to me. American poets have a certain irreverence to poetry that I find really appealing.

It’s a similar approach to that of Deryn Rees-Jones.

She is particularly brilliant with pop culture. She wrote this poem called ‘Love Song to Captain James T Kirk’ in which she imagines that she’s on-board the Starship Enterprise and having sex with William Shatner. It’s a hilarious poem. In the first section of My Family and other Superheroes, you can trace the influence of that poem and Wojahn’s Mystery Train.

In your work there are these micro moments of family life that are often set against this macro vision of global pop culture.

Absolutely. So many of our family moments take place in front of the TV. Like in the sitcom The Royle Family – part of the way that the Royles bond as a family is through watching TV. I think in many ways pop culture reflects the family back to us, so that it kind of feeds into or influences our experiences of our own families.

I grew up in Risca, which isn’t quite the valleys but getting there, so I experienced several nostalgic twangs on reading My Family and Other Superheroes. I had a very quiet, bucolic childhood in a small town and then, during the 80s, video rental stores opened up and in came satellite television, and suddenly pop culture burst in from the outside world. So I was experiencing a strange insular existence while being connected to the wider world, culturally speaking, at the same time.

There’s a poem in the book titled ‘Owen Jones’, which is about a guy who stands outside the betting shop in Risca – he’s probably there now if you drove past. Risca happens to be just down the road from where I live in Crosskeys. They’re both insular communities, which gives you a kind of intimacy with the local characters. I think that’s definitely informed my people watching, my upbringing in an intensely tight-knit, gossipy community where very little is private.

There’s also a strain of Welsh folklore, of self-mythologising that you seem to be exploring in that collection, turning local characters into heroes and incorporating pop culture heroes into the life of your family.

Well that was a slightly cynical marketing ploy – which is a ridiculous thing to say about poetry I suppose – but someone once told me that if you wrote a poem about your father then your father might read it but no one else, whereas if you write poems about Sophia Loren, Evel Knievel or Back to the Future you might reach out to a wider readership. A lot of the landscape poetry that I read leaves me slightly cold but Deryn Rees-Jones’ Star Trek poem seemed to speak directly to me and my life experience.

What keeps coming through your collection is this sense of the ephemerality of pop culture running parallel to the multi-generational family, which is a historical constant. As everything else shifts and changes, the family is always there, surviving.

I went to a reading given by the Scottish poet Niall Campbell – his first collection with Blood Axe is wonderful and completely different to what I write – and he talked about his poetry as being a dialogue with the past that also looks towards the future. I guess I think of my poems in the same way. But there is a risk with this pop culture stuff, which is that the poems might have a limited shelf life. In fifty years’ time is someone going to know or care about Ian Rush scoring a goal or the Back to the Future movies? I don’t know, maybe they will. I worry about that. The payoff, of course, is accessibility.

It’s really important to you that your work is accessible and reaches a wide audience?

There’s also an aspect of sitting in your room with a pen and a bit of paper, wanting to make those hours, days and weeks as much fun for yourself as you possibly can, and writing about Ian Rush or Evel Knievel is a way of doing that for me. I don’t think you should ever take yourself entirely seriously as a poet. The playfulness of the Back to the Future references in my work is a way of fooling myself that I’m not writing a ‘serious’ poem.

Taking part in festivals like Velvet Coalmine, is that also central to your mission as a poet – to directly engage with the public?

I think poems are written to be read aloud to people, and I think the feedback I get from live audiences, the engagement I have with them is absolutely essential to my work.

What about your future plans? Tell me about your next collection.

One idea I’m working on is a collection about the generation I was at school with. It’s about twenty years now since I left school and I’m thinking about a series of character sketches about my school friends, about people I lost contact with and what life has done to them. Another thing I’m working on is a book about Capel Celyn. I have a bunch of contacts and hope to do some interviews with people who lived there, and the sons and daughters of people who lived there.

That seems to be a general anxiety in your work about the dangers of forgetting, particularly in your poem ‘Capel Celyn’. There’s a fear that the community that is so dear to you might one day disappear and be forgotten.

Well two or three generations back, no one was writing about people from my family, or my part of the valleys. They didn’t have the opportunity to write about it themselves, either through lack of education or whatever. There is a risk that if you don’t record and preserve that life then it may be lost for good.

Jonathan Edwards will be reading at Velvet Coalmine’s Poetry at Preachers event on Thursday 3rd September at 7:30 in Preachers Bar, alongside Patrick Jones and Clare E. Potter. Iain Richards will also be discussing the life and work of Alun Lewis with Brian Roper.

Velvet Coalmine’s Literature Sunday event is 6th September (12 – 5pm) at Preachers Bar, Blackwood. A line-up of leading Welsh writers includes: Gary Raymond, Gee Williams, Rhian Elizabeth, Cynan Jones, Rachel Trezise, Francesca Rhydderch and Jo Mazelis.

For info and booking go to: http://velvetcoalmine.com/whats-on/literature/