The poet-priest R.S. Thomas spent a lifetime gazing at the sea – an encounter which is preserved in poetry which has become a landmark of 20th Century Welsh literature. His fruitful patience has much to teach us in this epoch of unprecedented climate breakdown, argues Alex Diggins.

There are few livelier opening passages in literature than Moby Dick’s. Once Melville’s famous throat-clearing injunction is out the way, he embarks on a description of the beguiling power of the ocean, illustrating his point by way of a tour of Manhattan:

Circumambulate the city of a dreamy Sabbath afternoon. What do you see?–Posted like silent sentinels all around the town, stand thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries. Some leaning against the spiles; some seated upon the pier-heads; some looking over the bulwarks glasses of ships from China; some high aloft in the rigging, as if striving to get a still better seaward peep. But these are all landsmen; of week days pent up in lath and plaster–tied to counters, nailed to benches, clinched to desks. Strange! Nothing will content them but the extremest limit of the land.

After this survey of the city’s sea-gazers, he concludes lustily: ‘Yes, as every one knows, mediation and water are wedded for ever.’

It’s hard to disagree: the sea’s capacity to provoke philosophising and verse-mongering in equal measure is well attested to. Amateur bards and metaphysicians of all stripes have reached for the ocean as inspiration and image with almost as much frequency as that other threadbare stand-in for infinity: the night sky. But occasionally a writer surfaces who startles through acuity, vividness and originality with which they approach this tried-and-tested theme. R.S Thomas is such a writer.

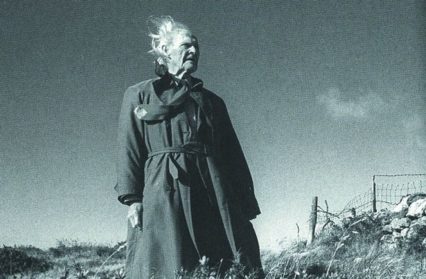

R.S. Thomas was unabashedly one of Melville’s ‘silent sentinels.’ Much of his life was spent on the coast, and he was a writer who spent his days ‘wearing his eyes out’ (‘Sea Watching’) on the ocean. The sea was one the great – if not the greatest – touchstones of his work. And its sights cleave almost intuitively to the poetry he produced during his fifty-year career.

Intimate and confessional, inhuman and timeless – the many and varied uses to which R.S. Thomas put the sea over his career tell us much about the value of patient observation; of modesty in our knowing; and, above all, how we might begin to re-stitch our relationships with the natural world that have come so disastrously unravelled. As Thomas’s sea poetry continually remind us, as a species, we share the ‘brief platform’ of existence with uncounted other presences – and there is hope, as well as responsibility, in that thought.

Autobiographical affinities

R.S. Thomas was born within the sound of the sea; it was the backdrop to his childhood. Brought up in the port town of Holyhead on the island of Anglesey, he remembered, in the third poem of The Echoes Return Slow, gazing down onto its harbour: ‘a forest of masts, where ships of sail sought shelter from the storm.’ Through these sights, he writes, ‘dreams were laid at the roots of a boy’s curls.’ A quality of wide-eyed wonder, a sense of expansive excitement, characterises Thomas’s depictions of his port town upbringing. He wrote in a letter to his friend Raymond Garlick, a fellow poet and critic, that: ‘It was Holyhead itself that made me what little of a poet I am. A little town, with a glorious expanse of cliff and coastal scenery. I shall never outgrow my hiraeth for it.’

Hiraeth: the word resists translation, approximating an idiosyncratically Welsh mixture of nostalgia and longing. But it recurs time and again in Thomas’s writing, and its usual subject is the sea. His autobiography Neb is useful here. Towards its beginning, he recalls how even at his rectorship at Manafon, one his first postings as a priest – exiled from the sea in the rolling hills of Montgomeryshire, the green heart of Wales – when out walking: ‘He would perhaps meet a shepherd who would say to him, “You can almost smell the sea today.” All this was enough to provoke his hiraeth.’

Later he admits in a crucial passage: ‘If one took a map of Wales, it would be easy enough to trace his geographical journey from being a child in Anglesey to being an old man in the Llyn peninsular.’ He describes this journey, through the succession of parishes he lived and worked in, as ‘a kind of oval’ that began and ended within sight of the ocean and his boyhood home of Anglesey. As Jason Walford Davies notes in his introduction to Neb, ‘The return is universalised in that it is seaward.’ We should be wary, though, of the ‘easy enough’ explanation; assuming guises, throwing voices, and seeding puns were all part of Thomas’s life-long project of remembrance. How much the neat cartography of his life can be ascribed to intention or design is impossible to tell. Nonetheless, there is winning sense of resolution at the thought of him on the Llyn peninsular gazing across at Anglesey. After all, as he wrote in Echoes, from that vantage point he could ‘look back over forty miles of sea to his boyhood forty years distant’. His was a lifelong project of looking – and yearning.

A family, all at sea

A similar sense of boyish ardency clings to Thomas’s few depictions of his father. Thomas Hubert Thomas served in the Merchant Navy in the First World War and subsequently plied the ferry route between Holyhead and Ireland. And to R.S it seemed his father’s profession magnified him to quasi-heroic proportions. In Echoes, Thomas Hubert becomes ‘the father travelling in “oils and grease” between the rougher surfaces of the ocean’. Elevated through the alchemy of a small boy’s awe, Thomas Hubert is no longer just a sailor but the boat itself: daring the ‘rougher surfaces of the ocean’ through his wit and will alone.

Once Thomas Hubert was forced to retire through deafness though, R.S pitied the wastage of his potential. In the poem ‘Salt’, R.S hears the long-dead ‘voice of my father/ in the night with the hunger/ of the sea in it and the emptiness/ of the sea.’ In fact the whole poem – which is of unusual length for R.S, stretching over several pages – is a touching but uncanny elegy to Thomas Hubert and his vocation. The voice slips uneasily between father and son, as R.S both inhabits and addresses ‘the sailor/ docked now in six feet of thick soil.’ There is a clear sympathy for his father for whom ‘the atlas was once as familiar as a back-yard.’ But who is forced to abandon ‘the deep sea’ and work ‘the narrow channel’ of the Irish Sea as a common ferryman.

However, if the poem is sympathetic towards his father, there is a distaste on disgust for the domesticity that called him home. ‘I must listen to him complaining,’ R.S recalls. ‘A ship’s captain/ with no crew, a navigator/ without a port: rejected/ from the barrenness of his wife’s/coasts.’ Children, homelife, a wife – these are the true dangers in poem’s schema which work with an insistent logic to emasculate and bind the once-proud soul of Thomas Hubert to Holyhead, ‘a town you had no love for’. Watching the broken figure of his father, deaf and hunched in an armchair by the fire, R.S sees both the freedom the open ocean embodies and the cruelty when that freedom is irreparably snatched away.

The sea, then, had an extraordinary fertility in Thomas’s imagination and his poetic parleying with his upbringing. The clarity it brought his autobiographical poems may have been hard won, cruel even, but it nonetheless lends them a rigour that approaches truth. It is unsurprising, therefore, that the sea – and the ways of looking at it – became a potent symbol through which his long first marriage to the artist Mildred ‘Elsi’ Eldridge (1909-1991) was mediated.

Approaching Elsi

Throughout his poetry, Thomas’s relationship with Elsi is dwelt on in remarkably confessional detail. It is also rendered with striking frequently through maritime imagery. Just as Thomas’s hiraethcaused him to see in the land-locked Manafon countryside the bold lineaments of the Anglesey coastline; so too, were the complex undertows of longing, rebuff, affection and jealousy that coursed through his first marriage salted down and rendered through oceanic language.

In ‘He and She’, startling insight into their relationship is gifted. Though the couple of the title are anonymous, they are recognisably Elsi and Thomas, steeped in half a lifetime’s union. ‘Seated at table –/ no need for the fracture of the room’s silence: noiselessly/ they conversed.’ A watchful intimacy is evoked; but it is an intimacy which roils with unspoken transaction.

Were there currents between them?

Why when he thought darkly,

Would the nerves play

At her lips’ brim? What was the heart’s depths?

There were fathoms in her

too, and sometimes he crossed them

and landed and was not repulsed.

Such uncaging of the heart’s calculation is discomforting. This is not an easy poem to parse. But then again, Thomas suggests, neither is the marriage depicted in it. It is presented as a relationship of darting, daring proximity; of braving the ‘fathoms’ and the ‘currents between them’. Thomas casts himself as a hesitant voyager; uncertain of his journey, grateful for his safe arrival. Like a pilgrim contemplating an immram, a Celtic-Christian wonder voyage, he journeys towards the uncharted reaches of his wife’s love – gazing across the straits of their relationship just as he looked back from the Llyn peninsular to his ‘boyhood forty years distant.’ It is a modest and moving final image.

This modesty, this lightness-of-touch, becomes characteristic of Thomas’s poems to and about his wife as she gradually succumbed to a series of long illnesses. Indeed, the image of the ‘heart’s depths’ find its most powerful expression as the crux of the poem which concludes TheEchoes Return Slow. That poem is a bruisingly poignant tribute to the twin pole-stars of Thomas’s love: ‘the timeless sea’ and Elsi. Again, Thomas serves as witness, a watcher over far horizons.

I look out over the timeless sea

Over the head of one, calendar

To time’s passing, who is now

At the last month, her hair wintry.

By happenstance, a draft of this poem had been placed next to ‘July 5, 1940’, a poem written to commemorate Thomas and Elsi’s wedding day, in his archives at Bangor University. Thus could the reader – performing a similar act of gazing to the poet – look across, page to page, the full span of their marriage, the Alpha and Omega of their love. And this coincidence made it especially apparent that while there is a contrast evoked between the ‘timeless sea’ and Elsi whose fading has become a ‘calendar/ to time’s passing’, there is a corresponding insistence, gentle yet passionate, that such a contrast has no real meaning. Instead, a sense of communality is stressed as Thomas – humble, wondering – suggests he has, ‘nothing to hope for but that for the love of both of them he should be forgiven.’ After all, as the poem concludes: ‘Over love’s depths only the surface is wrinkled.’

A promontory is a bare place

But if the sea could memorialise the most shockingly intimate moments of Thomas’s life, then it could also dramatize the profound turbulence that appeared to afflict this poet-priest’s faith. Thomas’s God, as many critics have noted, was the deus absconditus, the absent deity. And consequently, much of his metaphysical poetry is gnawed with absences, silences, gulfs and gaps; it echoes with addresses to a God who is not only apparently deaf to the entreaties of his servant, but may have absconded his creation entirely. And this painful awareness of unanswered insufficiency is obsessively characterised as a treacherous sea voyage, of looking out across an ocean, dark and uncertain. As Tony Brown notes, ‘the determined struggle against the sea […] becomes an image of the necessary resilience of the believer, struggling to maintain his faith.’ It is a trope which becomes particularly noticeable after Thomas had retired to a remote cottage at Sarn Rhiw on the tip of Llyn peninsular, which gazed fixedly at the breakers that barrelled into the bay commonly called Hell’s Mouth. There, as during his childhood, his nights and days were filled with the sight and sound of the sea.

It is also at Sarn Rhiw that his thoughts appeared to snag on an idea he first encountered in Kierkegaard: ‘without risk, there is no faith.’ A conviction which found fuller expression in Kierkegaard’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript:

If I wish to preserve myself in faith I must be constantly intent upon holding fast the objective uncertainty, so as to remain out upon the deep, over seventy thousand fathoms of water, still preserving my faith.

It seems the conceit of belief as being ‘over seventy thousand fathoms of water’ resonated deeply with Thomas, leaving its tidemarks throughout the verse produced during this period. It becomes, for instance, the central preoccupation of the poem ‘Balance’.

No piracy, but there is a plank

To walk over seventy thousand fathoms,

As Kierkegaard would say, and far out

From the land. I have abandoned

My theories, the easier certainties

Of belief. There are no handrails

To grasp. […]

Is there time

On this brief platform for anything

Other than the mind’s failure to explain itself?

Implicit in this poem is a contagious existential threat. It shivers at the thought of the ‘plank’ precariously balanced over the mute blank of unbelief, presaging utter dissolution. Yet, there is a strange compulsion to the thought of ‘abandoning […] theories, the easier certainties of belief’. The ‘plank to walk over seventy thousand fathoms […] far out/from the land’ has its own peculiar siren-song: a sense of pre-ordained necessity drives the narrator’s braving of it. The price of faith, the poem suggests, is a continual awareness of one’s insufficiency for the task; the price of living on ‘brief platform’ of existence, it further contends, is a coming to terms with the lack of time for ‘anything/other than the mind’s failure to explain itself’. There is, therefore, in this most bleak and unforgiving of ontologies a kind of corresponding hope; a stoic acceptance that perhaps accords with the muttered prayer of the sailor once out of sight of land: ‘Deliver me back safe again. Do not leave out in this vastness alone.’

The sea, then, could represent the unravelling of faith – and the self – as in Kierkegaard’s fearful vision. But a counter-narrative also works within many of Thomas’s poems: that its unhurried, timeless rhythms conjure in the watcher a kind of patience; a modesty which might in time open up to joy at rubbing up against the elemental textures of the world. In ‘Sarn Rhiw’, Thomas’s sea-gazing sharpens to Zen-like acuity: ‘the salt current swings out of the bay/ as it has done time out of mind./ How does that help?/ It leaves its writing on the shore.’ The sea has been reconciled from swallowing maw to calming metronome which, while still existing on an inhuman scale, is nonetheless legible to the observer: ‘it leaves its writing on the shore.’

And it is this final idea – of watchful patience and legibility – that has most to offer us who are both inheritors and perpetrators of this current geological epoch, the Anthropocene. Gnawing panic, or conversely a wilful ignorance, are all too easy responses to a problem which seems too vast, too difficult to confront. Thomas’s sea poetry offers a third way. To my mind, there is something particularly productive, hopeful even, about the ways he used the sea in his verse and especially in the idea of a coming-to-terms with the sea’s otherness, its resistance to human timeframes, and its ultimate unknowability. The ocean’s endless patterning may be finally inscrutable (perhaps that explains its draw for Melville’s legions of watchers), but Thomas proposes that this illegibility should be celebrated, not resisted. Looking, he suggests, does not always imply knowing. And that is a precious revelation.

Helen MacDonald expressed this well in her essay ‘Tekels Park’: ‘[The Anthropocene] prompts us to take stock. During this sixth mass extinction we who may not have time to do anything else must write what we can now, to take stock.’ Thomas’s lifelong infatuation with the sea could be described as a particularly fruitful project of ‘tak[ing] stock’. As he wrote in ‘West Coast’, ‘What is existence/ but standing patiently for a while amid flux?’. To say we now inhabit a planet in ‘flux’ would be to commit a grossly negligent understatement. But it would also be true. And Thomas’s work which measures, uses, dreams with and summons the strange magic of the ocean is, above all, a record of ‘standing patiently’. It is a testament to a peculiarly personal watchfulness, care and stewardship. We might do worse than emulate it.

Alex Diggins is a writer and journalist based in London. He is currently working on a book about islands, spirituality and climate change. You can follow him on Twitter here.

Photo Credit: Howard Barlow

Recommended for you: Memories of R.S. Thomas