Romanticism in the Welsh Landscape is a major exhibition at MOMA Machynlleth from 19 March to 18 June. With over 60 works dating from the late eighteenth century to the present, it’s the most substantial exhibition MOMA has ever held. Its guest curator Dr Peter Wakelin talks about the experience of conceptualising and selecting it, and shares some of the star exhibits.

Just over a year ago Ruth and Richard Lambert of MOMA Machynlleth asked me if I would consider curating an exhibition for them. In 2010, I curated their show Art for Children, which was one of the most popular they had held and – for me – a lot of fun to do. MOMA has reached its thirtieth anniversary a hugely admirable gallery run almost entirely on voluntary resources. It has grown organically from its original chapel and shop, bridging an alley and rejuvenating a derelict tannery, to become a substantial art venue. Last year it became an accredited museum.

The choice of the new exhibition was up to me, bearing in mind a two-point brief. The first was that it should be a major show. The second was that it should look at some aspect of landscape, a subject of huge breadth and a passion for many people, including MOMA’s generous recent supporter, Professor Richard Mayou.

I love Welsh landscapes, and I love landscape-based art, so it was a pleasure to come up with ideas about how to approach a show with something fresh to say. The idea the Lamberts and Richard Mayou liked best was an exploration that I had been mulling over for some years of the role of the Welsh landscape in the development of Romanticism in visual art. While I was Director of Collections at Amgueddfa Cymru-National Museum Wales Nick Thornton curated the impressive Wales Visitation: Poetry, Romanticism and Myth in Art, but I was sure there was plenty still to explore. Romanticism in the Welsh Landscape, as we have called the MOMA exhibition, develops an argument that Wales has had a key role to play in Romantic landscape art. It’s a story worth telling both in its own right and as a corrective to the over-emphasis on Englishness and English artists in the history of British landscape painting.

The Welsh influence on Romantic landscape has been cross-generational. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries early Romantic artists were inspired to treat landscape expressively by the Welsh-born painter Richard Wilson. In the generation after Wilson, touring Wales was a transformative experience for many painters, including J. M. W. Turner, who came first aged 17. The narrow art-historical view that mid-twentieth-century neo-romanticism was an English movement needs adjusting – Wales fostered the talents of David Jones and Ceri Richards and was a transformative influence on key neo-romantic painters, especially John Piper, John Craxton and Graham Sutherland, who said Pembrokeshire taught him to paint. Today, the Welsh landscape continues to inspire artists of a Romantic sensibility as diverse as the painter David Tress and the conceptual artist Tim Davies.

The concept of Romanticism isn’t the simplest of hooks on which to hang an exhibition, though luckily the works of art start to speak for themselves once assembled in a gallery. The word describes ways of thinking rather than a well-defined movement. One key quality of Romantic art, at the time of its origins and today, is that it rejects objectivity in favour of capturing personal responses – feelings such as awe, confusion, sadness, joy and love. Unlike the classical tradition, Romanticism doesn’t present ideal forms but instead looks to irregular, emotive places and their associations in the mind. Many Romantic artists have been, and are, drawn to subjects that evoke the power of nature, the deep past, mystery and the spirit of place.

The Romantic country

According to John Ruskin, Richard Wilson was the earliest painter of ‘sincere landscape art, founded on a meditative love of Nature’. He began to paint landscapes in his mid-twenties, and then to concentrate on them from his stay in Italy of 1750-7. There, Wilson had studied to produce idealised classical landscapes, but his temperament was for the spirit and particularity of places. Was this the first glimmer of Romanticism in landscape? Some of Wilson’s most directly observed work back in Wales certainly has a warmth and appreciation not found in idealised landscape, and an expressive depth very different to that of the topographical records made by early watercolourists. The exhibition includes, from Manchester City Galleries, his view of the Mawddach valley, which makes its real subject the massif of Cadair Idris, presented as an object of beauty and grandeur in its own right. A few years earlier, Wilson had been high on the mountain and painted Llyn Cau, Cader Idris (1765-7, Tate), which may be the earliest painting to treat the upland wastes themselves as worthy of depiction. It anticipated by years the Romantic movement’s fascination with the mountains. Ahead of its time, it remained unsold in Wilson’s studio.

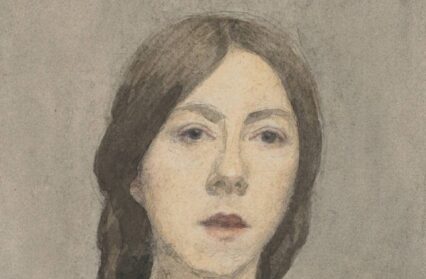

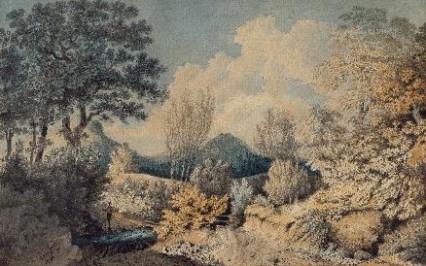

Wilson’s student Thomas Jones went on to paint views that glowed with feeling for his home in Radnorshire. He was largely forgotten until the 1950s, when his sketches came to light and revealed his remarkable individualism and anticipation of artistic interests yet to be invented. Among his most compelling works are seven watercolours that he seems to have painted entirely for his own pleasure, to hang in his own house, two of which are in the exhibition. They are intensely personal studies of the hills just a mile or two from his front door at Pencerrig, near Builth Wells. In their gentle, meditative depictions of nature and the presence of a still, solitary figure, these drawings seem like love-letters to a landscape with which the artist is completely intimate – a quality they share with the pastoral visions produced thirty years later by Samuel Palmer, which in turn were admired and emulated by neo-romantic artists in the mid-twentieth-century.

From the end of the eighteenth century Wales became a magnet to visiting artists, mainly from lowland England, who came seeking wild nature and the country of the ancient British people. Many wanted to experience and convey the effect Edmund Burke had called the ‘sublime’, a response of fear and awe brought on by the vastness of mountains or the grandeur of ruinous destruction. The sublime mountains, waterfalls, mines and ruined castles of Wales became subjects through which to consider themes such as the individualism of Britain, the power of nature, the immensity of Creation and the devastation wrought by time.

For many young artists, such as Turner and John Sell Cotman, the dramatic landscapes of Wales were their training grounds; places which drew out of them innovative, personal artistic visions. Having grown up in flat Norfolk, Cotman first experienced mountainous landscapes on a painting tour of Wales, aged 18. He was stirred by the wild weather and rugged terrain and came back two years later. For the rest of his life he revisited in his imagination, making paintings like the one brought from Norwich City Art Gallery for the exhibition, which he did of Cadair Idris some thirty years on. Although Cotman became a hero to Modernists who – long after his death – recognised cool abstract values in his simplified planes of colour, a Romantic mind can be seen in his dramatic cloud-shadows and mesmerising reflections.

Wales and neo-romanticism

From the 1920s onwards, some innovative artists began to cross-fertilise the passions of the Romantic era with modernist ideas from Cubism, Surrealism, Expressionism and abstraction. This burst of what became known as ‘neo-romanticism’ is often seen as an English phenomenon, but Welsh artists and the Welsh landscape were decisive.

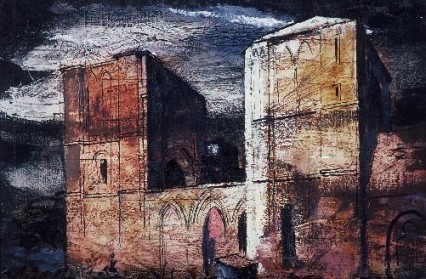

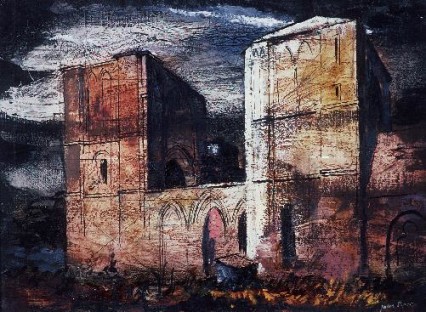

The two most influential British artists of neo-romanticism, Graham Sutherland and John Piper, spent formative periods in Wales from the 1930s. Sutherland’s painting was transformed after he experienced the ‘exultant strangeness’ of Pembrokeshire’s rocky skylines and hidden valleys and he responded in a newly free and expressive style. For Piper, Wales was a place of discovery as he left behind abstract art and found new ways to convey the emotional power of mountains and monuments. He painted a series of images of Llanthony Abbey in 1941. The abbey and its setting fast in the Black Mountains have fascinated artists of the Romantic era. Turner returned to the subject many times from youth to old age. Piper’s view was of the abbey itself, with textured surfaces and scintillating colours that lent the massive towers a powerful presence under the lowering sky. Works like this were radically new in the 1940s. Many other mid-twentieth century artists came to the valley – the exhibition includes works set there by not only Piper but Eric Ravilious, George Mayer-Marton, Glyn Morgan and David Jones.

In the case of David Jones, two of whose works are in the exhibition, his own Welsh heritage and stays in Wales created rich associations fundamental to his work. After the war he sought spiritual regeneration in Eric Gill’s Roman Catholic community at Capel-y-ffin. In the aftermath of his devastating experiences in the Great War, his fragile drawings interpreted the landscape as a place of peace and safety and the mountains and hills as manifestations of the praise of the Lord.

The Swansea-born artist Ceri Richards seldom painted identifiable landscapes but he produced vigorous Surrealist imagery informed by the natural world. He spent long periods at Pennard on the Gower coast, where he would draw the landscape with immense fluidity and confidence. The sculptor Henry Moore said, ‘More than any other painter of his time he understood three-dimensional form and knew how to express it on a flat surface.’

© Ceri Richards Estate / DACS

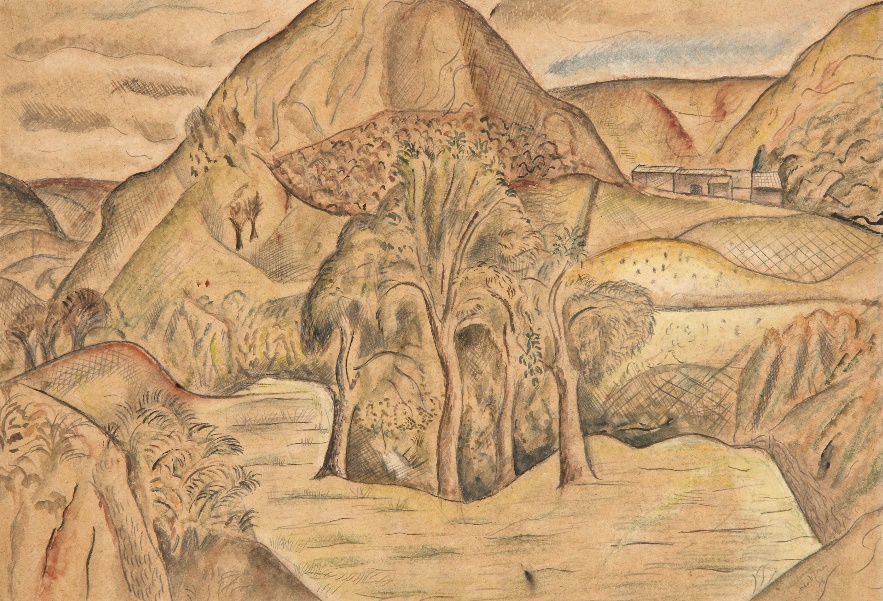

Younger artists such as John Minton and John Craxton found Wales just as compelling as the teenage Turner and his contemporaries had done 150 years before them. Minton was one of the artists most closely associated with the mid-twentieth-century flowering of neo-romanticism, and it is exciting to have in the exhibition a rare showing of his strange, compelling drawing Recollections of Wales, which has been described as among the masterpieces of the era. In 1943, stationed for army training at Barmouth, Minton found himself turning towards landscape as a subject. He read Graham Sutherland’s ‘Welsh Sketch Book’ and wrote of Barmouth, ‘The mountains are fine, mottled and serrated like Sutherland … swept by winds one can almost see roaring in whirlpools and eddies round the peaks and out to writhing grey sea.’ He produced his drawn elegy the following year. In it, the wind is evident, battering the trees across the pathway to the rising hills. The solitary figure is ambiguous: lost yet rooted in the landscape, female yet androgynous, wound for the tomb yet with one leg and one arm free. In this apocalyptic landscape, he/she seems to personify the force of nature and mourn the young men lost at war.

Other visitors who responded to the Welsh landscape included Ivon Hitchens and the refugee Expressionist Josef Herman, who was so captivated by the ‘sadness and grandeur’ of the Swansea valley that he made his home there for eleven years. A further generation of Welsh-born painters also absorbed neo-romantic interests and found their own approaches to the landscape. Many of them are now recognised as being among the greats of Welsh twentieth-century art, including John Elwyn, Arthur Giardelli and Ernest Zobole, all of whom are represented in the exhibition. Zobole’s mature work is utterly distinctive but it shared a Romantic perspective in a Modernist idiom, and it was a deeply felt tribute to his home landscape at Ystrad in the Rhondda valley.

Romanticism now

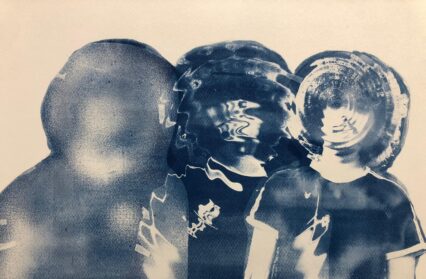

The last part of the exhibition represents art of the last thirty years that has engaged emotively with the Welsh landscape. The approaches of artists are more diverse then ever and their media have expanded from watercolour and oil paint to found materials, installations, text and digital video – Romanticism is living and evolving.

Some of these more recent artists have direct links to their predecessors. The paintings of Glenys Cour and the late Bert Isaac and Glyn Morgan continue the ‘cycle of nature’ theme of their tutor, Ceri Richards. The predominant characteristic of the work of Glenys Cour is her colour, but nature and its shifts and seasons is always present and she finds drama in skies, sea and landscapes. Many of her paintings show Gower at dusk or dawn, when its mysteries are deepened by shadows or veils of mist. Other artists are conscious of the Romantic tradition even though they work in different idioms: David Tress shares Turner’s obsession with extreme weather and Helen Sear’s videos look at landscape through Romantic eyes. The sublime is encountered in the paintings of Peter Prendergast and Maurice Cockrill or when Clive Hicks-Jenkins turns the coast of Amlwch red behind a scene of violence.

Visiting artists still come to Wales seeking subjects, for example Ed Kluz on the trail of lost houses and Charles Shearer clambering in decaying quarries. Shearer has produced new paintings of the Nantlle valley specially for the exhibition. Towards Snowdon from Penbryn Quarries is close to the view of Snowdon that Richard Wilson painted in around 1765 but Shearer looks across derelict slate workings rather than Llyn Nantlle and Snowdon itself has disappeared in the mist. He says he seeks in his work ‘an illusion of depth, space under the surface, a place for the mind’s eye to wander.’

Welsh identity and cultural politics interest today’s artists, as they did Richard Wilson and David Jones: Ivor Davies rails at the dispossession of families for firing ranges and Tim Davies mourns in allusive video Pembrokeshire communities slowly dying as properties change hands. In this continuing tradition of Romantic landscape, heartfelt love for the land of home is expressed as powerfully by Roger Cecil or Eleri Mills as it was by Thomas Jones in his emotive, glowing images two centuries ago.

Romanticism in the Welsh Landscape is showing at MOMA Machynlleth from 19 March to 18 June 2016. Open Monday–Saturday, 10am–4pm, admission free.

An accompanying booklet by Peter Wakelin is available.

Tel: 01654 703355