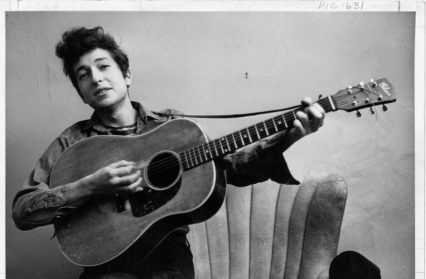

Novelist and broadcaster Gary Raymond traces a personal journey of his life-long relationship with the music of Bob Dylan as the cultural icon celebrates his 80th birthday.

The last time I saw a Bob Dylan gig, I said it would be my last. I said it out loud, in fact, as I turned my back to the stage, as my shoulders dipped and I tossed an empty cider can in the direction of the overflowing bins. It was in 2012, at the strange and ill-fated Hop Farm Festival in Kent, and I abandoned the man who had taught me more than anything about music, creativity, culture, than anyone else, in order to go and stand on the peripheries of a vast steamy tent across the valley to watch Primal Scream do their thing. I’d already seen Bob Dylan eleven times (or was it twelve? I lost count) in the sixteen years or so prior to that weekend, but it felt like the right time to say goodbye. Most people who have followed him on his Never-Ending Tour over the years have plenty of stories of ramshackle gigs with the famed unintelligible vocal performances and grungy pub rock backing band that often rendered one classic song indistinguishable from the other. But for many of them there is no break-off point. I had reached mine. There was no doubt in my mind.

That evening, the problem was not just that his voice was now so broken and hoarse that it was rattling my rib cage, and it wasn’t that one song sounded largely the same as the next (I’d acquired an obsequious ear for the often perverse rearrangements Dylan gave his most famous songs over the years on tour). No, it was more the feeling that Bob Dylan had had it, that he was past it, that he had finally become what he had always wanted to be, a jobbing musician, going through the numbers.

I’d seen him at festivals before and not had this feeling. Glastonbury ’98 he took the Pyramid Stage on a Sunday afternoon on the same bill as Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, Sonic Youth, Blur and others, and not for a second did he seem out of place or out of time. At the Phoenix Festival in ’95 on the bill with Suede, Tricky, and Public Enemy, he was just as vital as the young pretenders. In ’96 at Hyde Park for the Princes Trust Concert he made The Who look like a musical theatre revue. But now, in 2012, sharing a bill with old timers like Peter Gabriel, Parliament/Funkadelic, Psychedelic Furs, Patti Smith, and Dr John, it was Bob Dylan who brought the mood down. I’d been kind of expecting it. Almost hoping for it. Time to put my Dylan under lock and key in a chamber inside me somewhere. Carry him around with me, but time to move on.

Of course, it doesn’t happen that way. You don’t get to choose what opens you up. Last year he released his best album since 1997’s Time Out of Mind, and he’s released some fine albums since I said goodbye at Hop Farm. The man is irrepressible. The sixteen-minute single from Rough and Rowdy Ways (2020), “Murder Most Foul”, is a Dylan song par excellence, a darkly witty beatitude on the attitudes of the American mythos that pings from one epochal moment to the next. It’s up there with “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”, “Joey”, and “Brownsville Girl” for its epic sweep. And to top it off he dropped it on his fans out of nowhere, like he was Taylor Swift or something.

As well as his consistent output in the last decade of newly written studio albums, the Bob Dylan estate has been relentless in its issuing of “official bootlegs”. They stand as testament to his prodigious official output (39 studio albums, 12 live albums, and, so far, 15 of these bootleg series). It all stands as a reminder that even when wire-wooling his way through an unrecognisable cover of “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues”, Dylan is never anything other than the most vital person in the room.

I was introduced to Dylan’s music by my best friend in school – or did we become best friends because he turned me on to Dylan? I’m not sure which way round it happened. We were fourteen and sat next to each other in History class. The Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Volume One (1967) CD was slid across the grey formica like a forbidden treasure, that big old silhouetted curly haired head of his turned to me from the cover as if inviting me to join him in some commedia dell’arte. It’s a cliché, but it was the music I think I’d been waiting for all my life. I had been brought up on The Beatles, and although I could never forsake them, something about the slapdash nature of Dylan’s approach to his art spoke to me as if it were a one-to-one. He seemed – dare I say it – just as lazy as I was, just as shy, just as performative, just as ambitious, just as certain of his vision, as I was as a fourteen-year-old (and probably ever since).

I re-enacted the lyrics to “Subterranean Homesick Blues” across the back of my yellow History exercise book. The teacher, who was a bit fussy about book graffiti, didn’t seem to mind so much. My version of the song was filled with misheard words, and I’m sure if you could see the exercise book now it would look more like a found poem than a homage. My best friend, who was at the time a Hendrix aficionado more than anything, explained to me how Jimi came to record his iconic cover of Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower”, how someone had played the album from which it comes, John Wesley Harding, at a party and the guitar god was so taken aback by the apocalyptic vision entombed in the song’s four chord trick that he raced off with his Experience that night to record it in just a few hours. A few years later, we would become half-obsessed with Bruce Robinson’s Withnail and I (1987), and the Hendrix version would again come thundering into our lives and onto our weekend party mixtapes. Bob Dylan always would and always will swirl in and out of our lives like a fire breathing dragon, through his work, through the work of others, through a phrase here, an intonation there. I looked up to him, but he also felt like my friend. God, he was like Hitler to my Jojo Rabbit.

I read in a magazine an anecdote where Dylan and Leonard Cohen were having lunch in the ‘eighties – must have been ‘eighty-four or ‘eighty-five – and Dylan’s Infidels album had just come out. Dylan complimented Cohen on a song from his recent Various Positions. “How long did you take to write ‘Hallelujah’?” Dylan asked. “Overall,” said Cohen, “about eight years.” “Wow, man, that’s a long time to work on one song,” Dylan said. Cohen repaid the compliment. “I loved that song on your last album, ‘I And I’,” he said. “How long did it take you to write that?” Dylan gave that half wry smile of his. “About fifteen minutes,” he said. Cohen apparently spat out his soup.

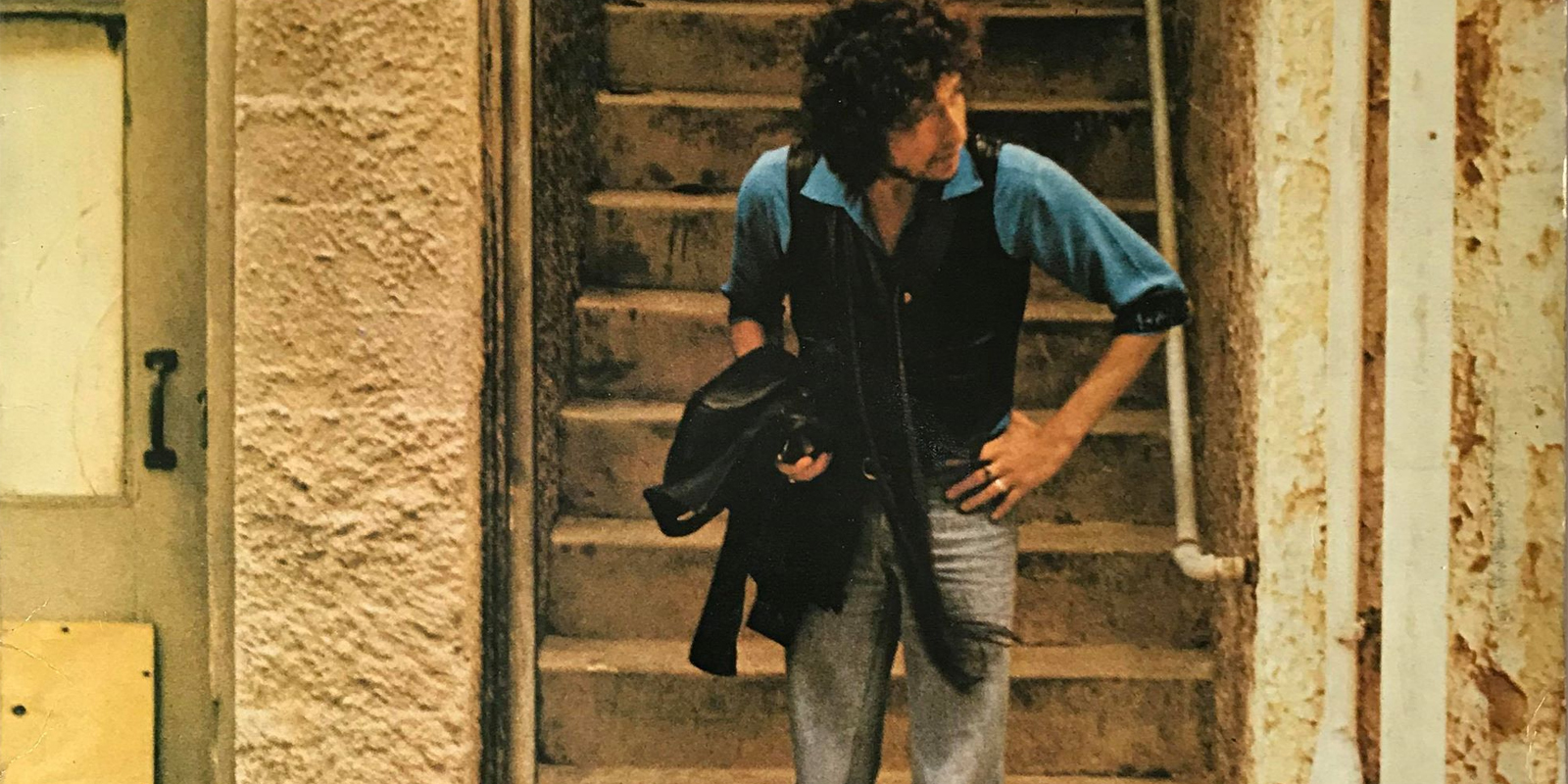

As a teenager we loved all the great songwriters, and Cohen’s Songs of Love and Hate (1970) has its place on Mount Olympus. But when it came to feeling down in the groove, you had to choose whether you were the real deal, or whether you were a charlatan. Thing is, you cannot choose whether you are the real deal or not. You either are or you aint. Dylan is the patron saint of charlatans. The adopted name, the Woody Guthrie drag, the polka dot Beat poet, the country star, the death mask, the born-again Christian, the leather-bound eighties stadium god, the blues man, the Louisiana necktie, the country gent, the jobbing musician. All of it is make-believe. Cohen was the real deal. No getting underneath that skin. Dylan was for me.

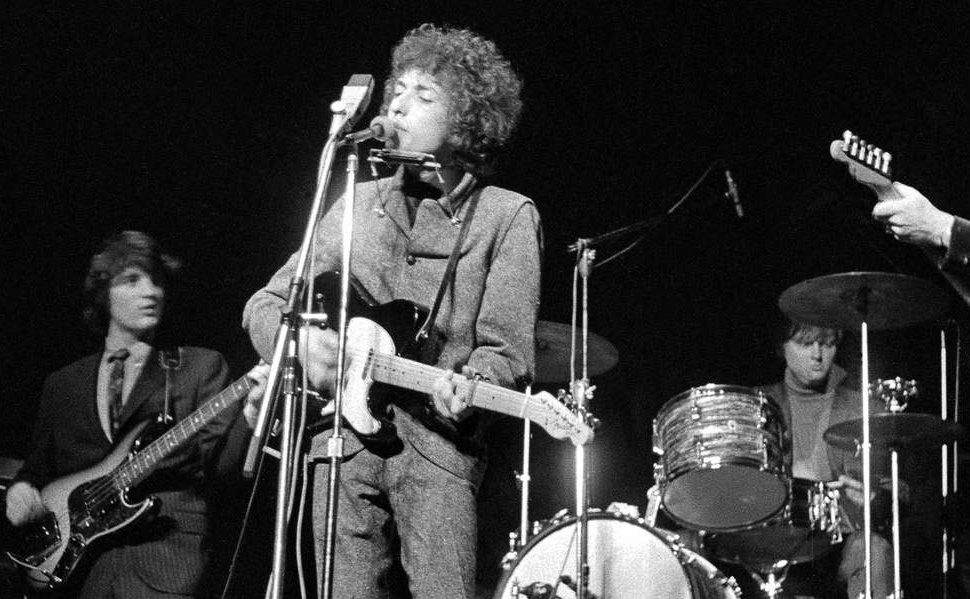

There was a restless energy to the idea of Bob Dylan, and his essence was more revolutionary, more punk than many other artists I was to get into for the first time in my teens. It wasn’t in the somewhat tame, preppy sentiment of “your sons and your daughters are beyond your command”, but it was in the self-belief that he was on the true path. In the ‘nineties hindsight was a wonderful thing. We could see he had been right all along; we could hear that he had been right. But at the time, in 1966, it must have looked borderline insane to go on that tour and have audiences pay for tickets so they could come and boo you. His backing band, The Band, reminisce about it now and you can still see them turn pale at the trauma of the memories. But Dylan wanted to go electric. Nothing was going to stop him following his gut. For a teenager that drive and passion to non-conformity, to forge a sound that kept your heart pumping was an electricity all of itself.

And it wasn’t just that go-your-own-way certainty. It was the laziness. You heard the stories and rumours of what he was like in the studio, that he didn’t do a thousand takes of one guitar track like The Beatles were doing for the white album, but you also heard it on the records, that attitude of get-it-down and move on, capture the moment like the bluesmen singing into Alan Lomax’s reel-to-reel on the porch. You can hear it in his out of tune guitar on “Queen Jane Approximately”, on Emmy Lou Harris trying to keep-up on “Oh Sister” or even in the rewritten lyrics of the live version of “Tangled Up in Blue” from Real Live (1984). That energy, that fire, that joy and grit, it was all teenager energy.

And the way he famously has had a habit of leaving some of his best songs – some of the best songs – off his records, floating in the ether for bootleggers to weave into the poetics of myth and rumour. “Mama, You Been On My Mind”, “Blind Willie McTell”, “Series of Dreams”, “Foot of Pride”, “Nobody ‘cept You” – the list is long and formidable, and for decades these songs were unobtainable but for the determined few. His attitude is singular, focussed, in the studio as on stage, he never plays to the crowd.

And his voice, the focus for Dylan detractors who “cannot get passed it”, but then you uncover a song like “Moonshiner” and hear that the charlatan has more poise, authenticity, and depth than the parade of wannabes who have tried to come after him.

And his blues harp playing. He plays it straight, a fizzled Gatling Gun of a player. Not a virtuoso harmonica player like Stevie Wonder, and not one to bend the notes like a prairie wind a la Neil Young. No, Dylan puts his harp out there, slides up and down it, but in the searching, time and time again, finds a cluster of notes to make the heart ache. Simple, no nonsense.

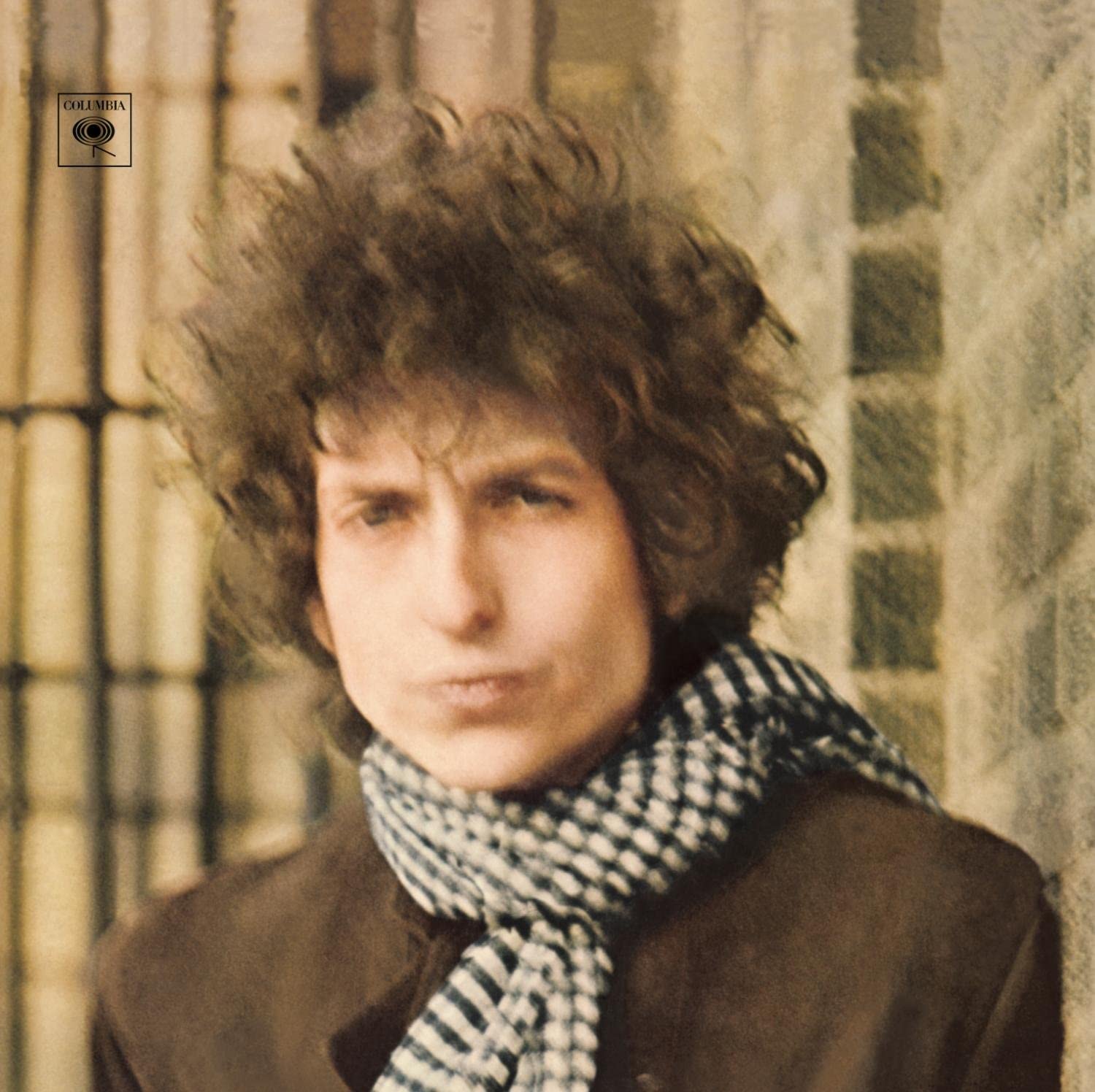

The Greatest Hits was a gateway, but also, like so much of Dylan’s amulets, it was never left behind. For years it was the only place you could hear one of his ‘sixties classics, “Positively 4th Street”, a song with lyrics and title and Hammond organ that placed it front and centre of his mid-decade high point. Blonde on Blonde, out in ’66, should have been the final word, the masterwork to which all subsequent output looks back. But it wasn’t. His next album was just as good, and then in the ‘seventies he had arguably three masterpieces in Blood on the Tracks (1975), Desire (1976), and Street Legal (1978). In the eighties, a fallow period, he ended it with the brilliant Oh, Mercy! (1989). The nineties saw him bring out two great roots albums in Good As I Been To You (1992) and World Gone Wrong (1993), and another masterpiece in Time Out of Mind (1997). But Blonde on Blonde is where it starts to get stratospheric. Those great albums before it like Freewheelin’ (1964), Bringing It All Back Home (1965), and Highway 61 Revisited (1965), they felt like boys having fun. Blonde on Blonde is like a Russian novel. A double album of sprawling absurdity, songs largely about nothing (didn’t someone once describe it as the greatest album ever made about nothing?), full of circus characters and hippies and swordsmen and princesses and roustabouts. But to me, it’s always been monochrome.

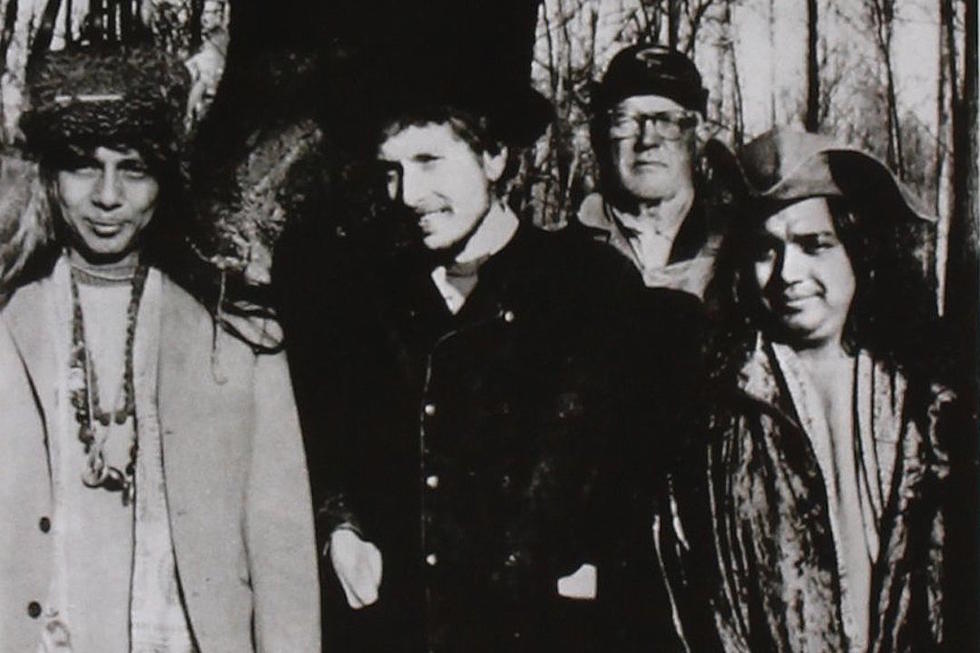

Perhaps it’s that curious out-of-focus photo of him on the cover. Maybe it’s the sound, the crisp looseness of those Nashville session players – the best in the world, used to playing to charts but here mostly improvising over a couple of takes with just the key changes for signposts. Dylan called the sound of it “wild thin mercury” which isn’t a description befitting the flower power tie-dye saturating the rest of rock music at the time. In ’67 the world of pop went technicolour. The Beatles released Sgt Pepper…, the Stones followed with Their Satanic Majesties Request. Huge concept albums full of classical pretensions in the brightest colours possible popped up all over the place. Dylan responded in ’68 with an album of Old Testament allusions played out with acoustic guitar and blues harp, bass and stripped back drum set up. On the cover, as if aiming to pastiche Pepper’s cavalcade of cardboard cutouts, Bob Dylan stands in the bleak midwinter of a black and white photo with a couple of native American trappers at his shoulders. They look like they’re about to go hunting Confederate runaways.

Another of my closest friends growing up, whose father was the foreman of the cemetery my parents’ house backed onto, showed me two CDs one day. We were about fourteen. One was N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton (1988), (which we went on to play incessantly, singing along with words no white kid should ever mouth, words which we knew if our parents heard us repeat them would have us grounded for life). The other was John Wesley Harding (1968). My mate, Rich, wasn’t so keen on the dour oppressive fire and brimstone of the Dylan album (and neither was his dad, who had given it to him), and so he said I could keep it. I read that Dylan had been holed up in his house in Woodstock, upstate New York, writing the songs that would form John Wesley Harding, leaving Country Joe and the Fish to hit the zeitgeist firmly on the nose up at Max Yasgur’s dairy farm (in reality, John Wesley Harding came out the year before Woodstock happened, but that wasn’t how I saw it back then, everything having neat significance in the building of the singular myth of Dylan). There was a photo – or at least I remember one – of Dylan bent over a family Bible with his thin beard and new crew cut, a Bible big enough for him to crawl into and sleep, the type with a plinth and lock and key, as he fashioned songs that got under my skin like nothing I’d heard before. The simplicity of “Wicked Messenger”, the drawl of the title track, the bar-room longing of “I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine”. I stared at the cover for months after Rich gifted it to me. I read about the hidden meaning those known as Dylanologists had deciphered from the shadows and dark corners of the smudged monochromatic image. That the turtle-necked faces from With the Beatles (1963) was secreted into a tree stump. Something else was somewhere else. All nonsense. I wanted to buy into it because it seems to say something supernatural, but I couldn’t see the things I was told could be seen. My eyes just wouldn’t play ball. All I could see, if I’m honest, was a splodge of shadow that kept turning my mind back to the time when we dared Rich’s kid brother to climb into the black maw of a collapsed grave. That was all I could see. The guilt. Staring back at me.

The first time I saw Dylan live was in Cardiff and I was sixteen years old. My brother-in-law, who I’d known all my life, asked if I wanted to go. He was a diminutive alcoholic who worked at the local bakery, and who was always in the background at family gatherings. But our relationship was punctuated with what can only be described as puncture marks through his veneer of the simple man living the simple, hard, troubled life of the working class. One time he sat me down and put on a CD engraved with the clasped hands of two cyborg lovers (? – that was how I saw it) and told me to “check out this arpeggio”. I would have been about thirteen or fourteen. We sat there silent for fifteen minutes as Pink Floyd’s “Shine on You Crazy Diamond” unfurled between us. (At some other point he played me the Steadman/Geldof Wall movie he’d taped off Channel 4. I still have nightmares about that sausage maker).

On other occasions he would have my sister call up my parents and ask if I wanted to go over and play chess with him. I would go. We would sit opposite each other and take it very seriously. So, my first Dylan gig I owe to these unsuspected outreaches. If my brother-in-law had been rich, a land baron or a member of the House of Lords, he would have been thought of as eccentric, rather than the man who fell out of a tree drunk at the feet of some ramblers on the Sirhowy Valley Walk at 9am one morning.

My cards were perhaps already marked out as far as my drinking future was to turn out by the time I was sixteen – listening to too much rock n roll, reading too much Kerouac, growing up in too much Newport – but that first Dylan gig was saturated in beer. We started with four pints at teatime in The Lamb near Newport train station, a coppers’ pub in which nobody batted an eyelid at underage me. Bob Dylan was to play at the venue then called the Cardiff International Arena. They’ve changed the name since, but not the famously wet and floppy acoustics that have ruined thousands of gigs over the years. I would see Dylan there again and again, the kick drum ricocheting off the back wall like air raid shells, guitar solos cutting through the fourth dimension like diamond encrusted swords of treble. It truly is an arse of a live music venue. But this night, in 1995, it was perfect, and it held its legend in the mid-air like a vessel descended from the visiting gods.

We stood so close to Dylan I could have touched him (not really – closest you could get was probably forty feet). He crooned in a billowy purple silk shirt, swung his hips, played the blues harp like it was Lester Young’s horn. By now his “All Along the Watchtower” held the form of his original but had the distorted rage of Hendrix’s re-imagining. “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” rolled and rollicked like a Kerouac road movie. When the haunted hanging of the open Dminor of “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power)” rang out, my brother-in-law put his hand on my shoulder and we lived in the rib cage of the chord for a suspended moment. Years later, my brother-in-law took a sucker punch in a pub fight and never woke up from the coma it put him in. Whenever I hear that chord, that moment, and that entire night, comes to mind.

I guess there has always been a line drawn between Bob Dylan and death. His early focus on the Civil Rights symbols of murdered African Americans like Emmet Till and Hattie Carrol etc. through to Slim Pickens slipping away on the river bank, gut shot, Katy Jurado tearfully guiding him off to “Knocking on Heaven’s Door” in Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973). Laura and Rob having sex in the car at her father’s funeral in High Fidelity (2000) because she just needs to feel something other than grief while “Most of the Time” comes in with the storm rain on the windscreen.

In 1997, on his album Time Out of Mind, Dylan sings as eloquently about mortality as anyone ever has, and he does it on several songs. “Not Dark Yet” takes the show. But then, so does “Tryin’ to Get To Heaven”. And then, so does “Standing in the Doorway”. Bob Dylan has always written most poignantly about getting old, even when he was a kid himself visiting his dying hero Woody Guthrie in hospital and coming out with the first self-penned song he ever recorded in 1961. If you have to ask what Bob Dylan has taught me over the years, it’s that he’s taught me how to process these gargantuan notions of love, sex, death and all that other stuff; and he’s given me lines of insight into what it is I aspired to be. He has given language to my unthought impulses. A desire to rage, a desire to be at peace. A desire to be in the right place for the right reasons.

When I first heard “Sign on the Window” from New Morning (1971) I heard the voice of my own heart seeing contentment in the world once the noisiness of youth had quietened down. “Build me a cabin in Utah / Marry me a wife, catch rainbow trout / Have a bunch of kids who call me pa / That must be what it’s all about.” That last line repeated euphorically as if the puzzle is solved. I used to belt it out from the shadows of the alleyways of the live-hard-die-young cliches I made the most of for a long time.

Last month my son was born, my first child, and those famed sleepless nights have given me the dubious opportunities to follow YouTube rabbit holes as far as they’ll take me. Amongst Australian news bloopers and Norm MacDonald gag reels, I’ve been watching Daniel Lanois interviews. Lanois is most important not for producing U2 or anything like that; no, he’s most important for bringing out of Bob Dylan the most important statements of his later years: Oh, Mercy! (1989) and Time Out of Mind (1997). In many of the interviews about Dylan he starts with “Most of the Time”, the first song Dylan handed to Lanois in ‘eighty-nine. He mentions the lyrics. “Most of the time / I’m clear focussed all around / Most of the time / I keep both feet on the ground / I can follow the path / I can read the signs / Stay right with it / When the road unwinds / I can handle whatever / I stumble upon / I don’t even notice / She’s gone / Most of the time”.

I don’t need thousands of pages of academic texts by hippies who grew up to be professors to tell me why Bob Dylan is a great poet, in the same way I don’t need them to tell me why Langstone Hughes, or Emily Dickinson, or William Carlos Williams are great poets. I also don’t need the other side to tell me why rock n roll isn’t poetry. Poetry helps you see round corners, and that’s all you need to know.

The predictable furore sounded when Bob Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 2016, the first songwriter to take home the medal since Rabindranath Tagore a hundred and one years earlier. For people who believe Dylan’s “Simple Twist of Fate” is worth less culturally than “…Prufrock”, or that John Wesley Harding has less literary weight than “The Second Coming”, it was a lowering of the intellectual gravity of the award. But the award was for “having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” and that he certainly has done, and for that he deserves the award. Dylan is credited (and it’s implicit in the Nobel committee’s dedication) with having coaxed rock n roll from adolescence into maturation, but he did more than this. He took Buddy Holly’s words of love and Charley Patton’s words of pain and created a mode of expression that no full generation had ever had before. He may not have any hits, but those songs inspired hit makers to evolve from moon-in-June ease to Rimbaudian explorations of themselves and the world, and they could do it all with that unshakeable feverish propulsion of the rock n roll backbeat.

When Bob Dylan won his Oscar in 2001, he delivered his ceremonial performance not at the Chinese Theatre in Hollywood like everyone else who had ever been nominated for the award before him, but via satellite beaming him in from Australia where he was currently touring. I remember sitting up to watch it, finding some half-illicit way to bypass the pay-per-view barriers of the Oscars at the time, to see Dylan, with his card-shark moustache and steamboat country and western outfit that was his thing at the time, peering in close-up to the camera for too long, his voice hitting the mic like the gravel churned up by flood waters. I remember being certain he couldn’t win it. The Oscar for best song was reserved for the likes of Celine Dion or Barbara Streisand or Carly Simon, not the likes of this grizzled old jobbing musician. But he did win. Of course he did. That’s the sort of thing Bob Dylan does. He confounds expectations, and somehow, he always manages to restore faith in the way things are. So, this is the long way round to saying that on that evening at the Hop Farm Festival in 2012 I wish I hadn’t sidled off to see Primal Scream (who were very good, by the way), but I wish I’d stayed to see Dylan out; I wish I’d been loyal, because being loyal to Bob Dylan has never not paid off.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, critic, broadcaster, and editor of Wales Arts Review.

Enjoy this exclusive playlist to compliment the article.

_______________________________________________________________________

Recommended for you:

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.