Ian McEwan’s oeuvre can be split into two distinct phases: pre and post-divorce. The Penny Allen years and the Annalena McAfee years. First the mystical, then the rational.

The disintegration of his first marriage to the faith healer, Allen, which culminated in her absconding to France with one of their children (McEwan had been granted sole custody, as well as a thousand pounds for defamation of his character), led to the longest period between novels in McEwan’s career. The five years between Black Dogs (1992) and Enduring Love (1997). Black Dogs, a poetical meditation on violence – that ‘disease of the human imagination’ – represents a fitting end to the first act, with its talk of black dogs that ‘will return to haunt us one day, somewhere in Europe, in another time.’ Enduring Love represented a new focus on science and rationality, even if it was a novel based around a made-up psychological disorder, De Clerambault’s syndrome.

It is easy, then, to think of those five years as being a chrysalis-like period for McEwan, with the writer who finally emerged in 1997 being a far sunnier and more stylish proposition. Gone were the novels about incest and dismemberment that had earned him the erroneous nickname of ‘Ian Macabre.’ Here instead were novels such as his universally adored, ‘Jane Austen… country house… one-hot-day novel’, Atonement, and his novel-in-a-day, Saturday, which appeared, at first, by virtue of its exquisite prose and its tackling of the 2003 anti-war demonstration, to be a novel of some extreme cultural and social significance. Ultimately, however, it harboured the worst denouement McEwan has ever given us. Indeed, if it gave us any cultural and social news it was that McEwan could no longer write convincingly about psychopaths. Tellingly, just as Jed’s obsession in Enduring Love had to be accounted for by de Clerambault’s syndrome, so Baxter’s violence in Saturday had to be accounted for by Huntingdon’s disease. There is a tendency in this phase two McEwan to ignore the rule of the short story writer, which his phase one self so often abided by: the idea that you must ‘show and not tell.’ These days he ‘tells’ quite a lot. But then he is in the business of writing novels not short stories.

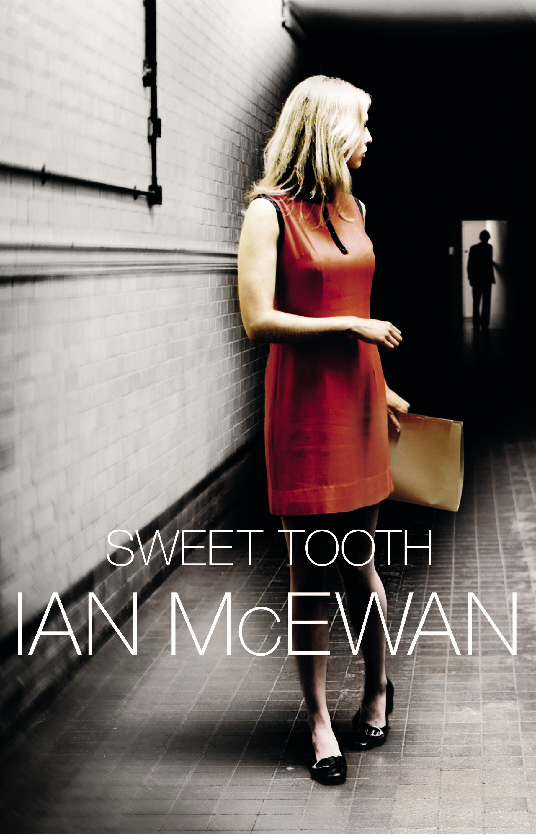

by Ian McEwan

320pp, Jonathan Cape, £18.99

It is interesting to note too that all of those novels were written in the third person whereas the majority of McEwan’s earlier works were written in the first person (from Jack in The Cement Garden to Jeremy in Black Dogs). So it is intriguing, and somewhat tantalising for fans of McEwan’s earlier fiction that Sweet Tooth is narrated by one Serena Frome – ‘rhymes with plume’. Would some of the old McEwan creep back in?

Speaking recently in the Guardian, McEwan spoke of his dislike for writing in the first person because it is ‘easy’, but that he couldn’t think of any other way to write Sweet Tooth:

I’ve got a prejudice against first-person narratives. There are too many of them. They’re too easy; it’s just ventriloquism and authors can hide their terrible style behind characterisation. Any number of clichés are permitted.

There is unquestionably some truth in this statement but at the same time unquestionably a good deal lot of nonsense too. Nobody would say, for instance, that David Copperfield was an ‘easy’ or a clichéd novel, any more than they would say Lolita or McEwan’s own Cement Garden was. But, in saying this, McEwan is giving us a good deal of information about his own project as an artist.

In ‘Mother Tongue’, the essential essay he wrote about his mother (whose ‘particular, timorous relationship with language… shaped my own’) and his beginnings as a writer, he explained how his early, minimalistic style was not born out of the scrupulous aestheticism, which the critics perceived it as, but out of anxiety:

In fact, my method represented an uncertainty that was partly social: I was joining the great conversation of literature which generally was not conducted in the language of Rose [his mother] or my not-so-distant younger self.

So we can see that it has taken McEwan a lot of hard work to get to the position he is in today, that of the most pre-eminent prose stylist of his generation, a title which had once seemed to be his friend Martin Amis’ by birth-right. And the reason his prose outshines his contemporaries is just because it is so evidently the work of a craftsman. In each book he writes, the prose feels even more fine-tuned that before. There is a fluidity and sense of possibility to his writing now which suggests he has attained maximum expression. The problem being that the things he wants to write about are maybe not as interesting as they once were. His last book, Solar, for instance, was billed as his ‘climate change’ novel – hardly a mouth-watering concept. It contained some of his most scintillating prose to date but was ultimately unsuccessful as a novel, collapsing, as with Saturday, beneath the weight of its own absurdly far-fetched denouement.

All of which brings me to the second aspect of McEwan’s ‘prejudice against first person narratives’. It often used to be said that McEwan was really a natural short story writer who is writing in the wrong medium (i.e. the novel) and certainly his first book, the short story collection First Love, Last Rites is among the most successful he has ever written. That was followed by another collection, In Between the Sheets, but since then he has only written novels, albeit ones which circle around that staple of the short story, the ‘single moment,’ to quote William Trevor, ‘that alters all subsequent time.’ This seems to suggest, again, the need to join in ‘the great conversation of literature’ as loudly and confidently as possible.’ As Frank O’Connor says, ‘Short stories are the preserve of outcasts’:

The novel can still adhere to the classical concept of civilised society… as in Jane Austen and Trollope it obviously does; but the short story remains by its very nature remote from the community – romantic, individualistic, and intransigent.

All of McEwan’s first phase novels could be described in those same terms. They are ‘remote from the community’, whereas, novels like Saturday and Solar are deliberately trying to engage with the ‘classical concept of civilised society.’

As soon as Sweet Tooth begins you are immediately struck by how similar to first phase McEwan the prose is. The language is extremely lucid, extremely pared back, cumulatively poetic, and very difficult to stop reading. You ask yourself: Is it simply because he is writing in the first person again? But no, the change is too complete. McEwan is consciously trying to write like his younger self and pulling it off with uncanny ease.

The plot of Sweet Tooth is, on the face of it, a simple one. Serena Frome, newly recruited to M16, is given the task of convincing up-and-coming young writer Tom Haley to accept a generous bursary from an independent art’s foundation. Unbeknownst to Haley the foundation is actually funded by MI6 as a part of a new campaign (the ‘Sweet Tooth’ of the title) to encourage writers who have the right sort of right-leaning politics. Serena, of course, falls in love with Haley and it is upon meeting him that we first begin to suspect that not everything is as it seems. Haley not only looks like McEwan, he writes stories like him too. Indeed, as if to emphasise the point, McEwan tells us the plots of several Haley stories in some detail. One is like a parallel dimension version of Enduring Love, while another is practically identical to McEwan’s early short story, ‘Confessions of a Kept Ape.’

The reasons for this only become fully evident at the climax of the book when there is a twist/trick which, without wanting to give too much away, readers of Atonement will be familiar with. Up until that point Sweet Tooth has been an enjoyable book – offering an exceptional portrait of Britain in the 1970s, mini-portraits of literary figures of the time like Martin Amis, Ian Hamilton and Tom Maschler – but a curiously uneventful one. The achievement of the twist/trick is to cast everything we have just read in a new, deeply profound – and even occasionally hilarious – light.

Because that ‘Sweet’ in the title doesn’t only refer to the MI5 plot Serena and Tom find themselves caught up in. It also refers to the story itself, which turns out to be the kindest and most romantic piece McEwan has ever allowed himself to write. It is ironic, and surely intentionally so, that in writing a book in the prose style of his younger self he has written a novel as far away from his younger self’s output as it is possible to imagine. A novel which is a love letter to the power of literature, and a love letter to a woman.

A real woman as it turns out. McEwan has spoken about how, in Sweet Tooth, he wanted to find a way he could ‘write a disguised autobiography’ and apparently Serena Frome is in part based on McEwan’s first love, Polly Bide, who he dated while he was an undergraduate at Sussex, and who died from cancer in 2003. Viewed in this light, McEwan’s multi-faceted, almost luminous portrait of Serena is all the more moving. It is, indeed, his most direct and successful attempt at dramatising the assertion that he made in the aftermath of 9/11. The assertion that ‘cruelty is a failure of the imagination’ and that:

Imagining what it is like to be someone else is at the core of our humanity. It is the essence of our compassion, and it is the beginning of morality.