Jodie Bond investigates perhaps ecology’s first-ever buzzword, the Anthropocene, and what The Act means for Wales and our future generations.

Are we being good ancestors? A question posed by the eminent virologist Jonas Salk and one that has a tendency to give pause. We care about our children and our grandchildren – maybe some of us will ever meet our great-grandchildren and care for them too. But beyond that?

We have more information at our fingertips than ever before, the globe is more connected and we are more aware of the impact of our action and inaction than at any other time in history. As with every generation, we hold the power to change the future, but we also have the luxury of living through a crucial window in which we can have a positive influence on a planet that is on the brink of sweeping change brought about by the acceleration of human activity.

The Holocene is the name given to the last 11,700 years of the Earth’s history — the time since the end of the last ice age. Our epochs are characterised by changes to the earth’s surface and scholars now propose that we have entered a new era: the Anthropocene.

The Anthropocene is not characterised by changes to our world caused by forces of nature but is instead marked by the impact our species has had on the Earth. We have lived in a remarkably stable climate; the Holocene has played the part of a garden of Eden, allowing our species to thrive, but this stability is being threatened by our own ingenuity. We flourished under the Holocene and through innovation and our hunger for advancement we have moulded our planet to fit our needs.

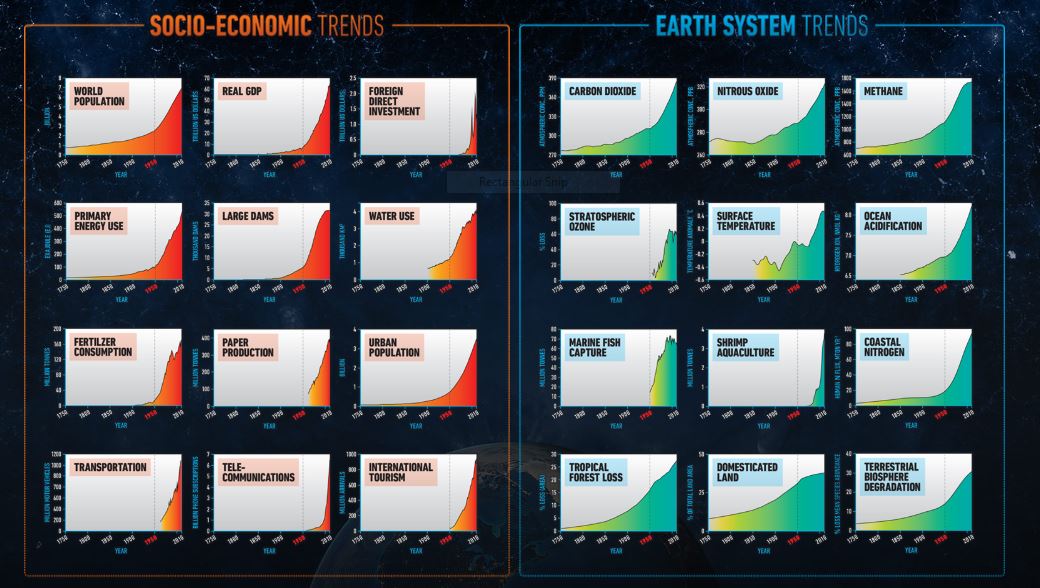

Most scholars concede that the Anthropocene began in 1945 when socio-economic and earth system trends began to increase dramatically after the second world war. Since then, we have seen sweeping changes to our planet. The period following the war has been coined the great acceleration. A sense of the problem can be established by a glance at a series of graphs, each detailing global changes. GDP, world population, ocean acidification, carbon dioxide levels, tropical rainforest loss, water use and energy consumption all rise in staggering curves after this period. Our impact on the planet has grown exponentially – and it’s continuing to rise.

A recent UN report claims that human activity has left us on track to lose one million species of plants and animals in a span of decades, a rate of destruction tens to hundreds of times higher than the average over the past 10 million years. Between 1980 and 2000, 100 million hectares of tropical forest were lost. Urban areas have doubled since 1992. We are losing sea ice at a rate of 13% per decade. Our oceans are due to containing more plastic than fish by 2050.

Closer to home, we see similar trends hitting our native animals; in Wales, one in fourteen species is at risk of disappearing altogether. Lapwing populations in Wales have dropped from 7,500 pairs in 1987 to just 700 last year. Yellowhammers have declined by 58% since 1995. Hares have declined by 98% since 1961.

Though it may seem the hour is growing darker, hope rises through our insatiable need to understand the world we live in. We have more data and processing power to understand our impact and have the expertise to roll out green technology. In the last year, we have seen a surge in urgency to repair the damage we are causing with the rise of movements such as the Extinction Rebellion and the thousands of children who have taken to climate strikes around the world.

In his latest book, Underland, Robert MacFarlane delves into the way the Anthropocene has shaped our world. “What does human behaviour matter,” he asks bleakly, “when homosapiens will have disappeared from Earth in the blink of a geological eye? Viewed from the perspective of deserts or oceans, morality looks absurd, crushed to irrelevance.” This perhaps explains our sometimes reckless behaviour as a species. Thinking in deep time is not something we are built to do. Try imagining what your hometown will look like in ten years time. Not unfeasible. But try thinking about how it will look in one hundred, one thousand or one hundred thousand years… Society, technology, the environment – all will have changed. The future branches out in myriad directions that become too numerous for us to contemplate. The effects of our actions today will cascade down the years, and though we may guess at their outcomes, they remain for the most part, unknowable.

Deep time is something we have always struggled to comprehend. Early estimates for the age of the planet were vastly miscalculated; Archbishop James Ussher pinpointed the date of creation to 4004 BC and Issac Newton elected a few years later with 3988 BC. In truth, the Earth is around 4.54 billion years old, a figure that confounds when contrasted with our own transitory time on Earth. Environmental historian John McNeil echoed the sentiment when he said, “Measuring things against a human lifespan is a normal and natural way to think.” Newton and Usher struggled to look back into deep time, just as we struggle to look forwards now. Looking so far into the past or future bears with it the prospect of giddying vertigo – we stare into an endless abyss.

In 2015, the Welsh Government sought to tackle the challenge of protecting the future by establishing the Well-being of Future Generations Act. The Act requires public bodies in Wales to think about the long-term impact of their decisions, to work better with people, communities and each other. The recent decision to reject plans for a new M4 relief road was, in part, down to this Act.

The Act is unique to Wales attracting interest from countries across the world as it offers an opportunity to make a long-lasting, positive change to current and future generations. It’s a positive step, but one that needs to be given legal powers and requires a replication across all global politics to create a positive planetary impact.

Fifteen million people have signed up to the website Ancestry.com, delving back through hundreds of years of human history. How different our ancestors must have been, in times before scientific medicine, industrialisation and digital technology. It’s no wonder the past fascinates us. But it also begs the question: how different will our descendants be? Will they look back at our generation with the same fascination we have with the past, or will they look back with resentment for the things we could have done to protect them, but failed to do?

During the Industrial Revolution, the global population stood at one billion and has since risen to seven billion. This is expected to rise again to over eleven billion by the end of the century. As each individual’s global footprint is on a trajectory to grow, the prospect of an increasing population is a worrying one. We will need to curb our “planetary spend” if we are to continue to prosper.

We must keep those eleven billion people in our thoughts. What world will we leave for them and their children? Our hunger for resources should not snatch away a future for our species, nor the 8.7 species with which we cohabit this planet. We must think beyond the boundaries of the Now and take responsibility for a future that extends beyond the lives of the present day. If we can hold onto this, perhaps the Anthropocene will mark an era that grants us the wisdom to see beyond our own lives. Perhaps we can learn to become good ancestors.

Wales Arts Review‘s News Service is supported by:

Jodie Bond‘s other Wales Arts Review articles are available here.