Phil Morris looks back at the cinematically skilful yet thematically abhorrent film The Birth of a Nation, exploring the uncomfortable ways in which it influenced the past, and affects our present.

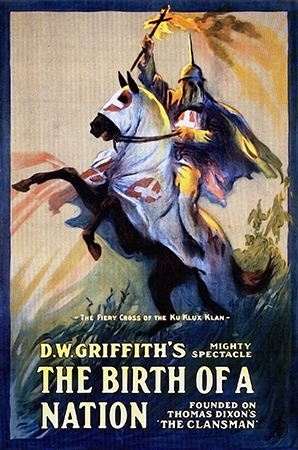

There is very little to recommend Peter Bogdanovich’s muddled comedy-drama Nickelodeon (1976) except for a late scene in which Leo Harrigan, a silent-era film-maker played by Ryan O’Neal, attends the premiere of The Clansman – to be retitled weeks later as The Birth of a Nation – directed by D.W. Griffith. We see the audience of 1915 sat open-mouthed in awe of the cinematic spectacle, breaking into rounds of rapturous applause at Griffith’s bravura set-pieces. Gunfire from the wings of the Clunes auditorium provide sound effects for panoramic battle scenes. The screening is interrupted at one point by an actor costumed in Ku Klux Klan regalia riding a horse at full gallop over a treadmill, to the giddy delight of the audience in thrall to the narrative’s epic sweep. The film ends, and almost everyone rises to noisily acclaim what they have just seen. Harrigan, however, remains seated, silent and immobile. The experience has pulverised him. He is not depressed by the racist politics of The Birth of a Nation, but by a realisation that he will never make a film that is as powerfully dramatic – or, even if he could, that Griffith had got there first as the originator of a new cinematic form. That image of a crushed, stone-faced Harrigan attests to the historical significance of Griffith’s masterpiece, which helped to found Hollywood and change cinema forever.

There is very little to recommend Peter Bogdanovich’s muddled comedy-drama Nickelodeon (1976) except for a late scene in which Leo Harrigan, a silent-era film-maker played by Ryan O’Neal, attends the premiere of The Clansman – to be retitled weeks later as The Birth of a Nation – directed by D.W. Griffith. We see the audience of 1915 sat open-mouthed in awe of the cinematic spectacle, breaking into rounds of rapturous applause at Griffith’s bravura set-pieces. Gunfire from the wings of the Clunes auditorium provide sound effects for panoramic battle scenes. The screening is interrupted at one point by an actor costumed in Ku Klux Klan regalia riding a horse at full gallop over a treadmill, to the giddy delight of the audience in thrall to the narrative’s epic sweep. The film ends, and almost everyone rises to noisily acclaim what they have just seen. Harrigan, however, remains seated, silent and immobile. The experience has pulverised him. He is not depressed by the racist politics of The Birth of a Nation, but by a realisation that he will never make a film that is as powerfully dramatic – or, even if he could, that Griffith had got there first as the originator of a new cinematic form. That image of a crushed, stone-faced Harrigan attests to the historical significance of Griffith’s masterpiece, which helped to found Hollywood and change cinema forever.

Charlie Chaplin once described D.W. Griffith as ‘the teacher of us all’, and while his reputation as the ‘father of film’ is not entirely deserved – as it would be to overlook the innovations of Georges Melies, Thomas Ince and Allan Dwan to name but a few rival directors – but it can be justifiably asserted that Griffith was the first director to deploy the techniques of the close-up, montage and cross-cut editing to such emotive effect at the service of a feature-length narrative. In a History of Narrative Film (2004) film, historian David A. Cook states:

In the brief span of six years, between directing his first one-reeler in 1908 and The Birth of a Nation in 1914, Griffith established the narrative language of cinema as we know it today.

Like Cervantes’ Don Quixote or Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, The Birth of a Nation is a paradigm shift in a nascent art form that is so influential it comes to define the form itself, foreshadowing its possibilities and outlining its potential scope. Griffith’s film is also, irredeemably, a contemptible piece of racist propaganda.

From as early as the writings of Russian formalists Sergei Eisenstein and Lev Kuleshov in the nineteen-twenties, it has been a trope of film criticism to regard Griffith’s mastery of technique and formalist innovations as qualities that can be regarded as distinct from the content of his films. In America this attitude also had its proponents, as Griffith’s manipulation in The Birth of a Nation of the racist fears of his audience, particularly their anxieties regarding miscegenation, became increasingly problematic for film historians and theorists as the history of the twentieth-century unfolded. As Scott Simon observes in his The Films of D.W. Griffith (1993):

His sentimentalisms have also been enough to turn many devotees into thoroughgoing formalists savouring his growing mastery in rhythmic editing and compositional style.

Yet such attempts to assess Griffith’s filmmaking technique, as something to be considered as separate from his ideology, were to misunderstand his work profoundly. Griffith’s innovations, deployed throughout The Birth of a Nation, were the means by which his racist message could be more deeply embedded within the darker recesses of the American collective unconscious. His cinematic technique was developed to serve his ideology and not simply as an aesthetic approach to be taken unquestioningly on its own terms. The uncomfortable truth, which must be acknowledged at the outset of any discussion of The Birth of a Nation, is that no artist, especially not one as crucial to his medium as Griffith, can be thought of as having created an aesthetic that functions independently of their political and cultural values. Both aspects of an artist’s work develop in symbiosis.

The Birth of a Nation mirrors the dichotomy at the heart of Wagner’s Ring Cycle, in that it combines aesthetic beauty with ugly politics. Like Wagner, Griffith was a nationalist whose ideals were rooted in bogus notions of racial purity and an agrarian, pre-industrial past steeped in a chivalric innocence. Both men were artistic innovators who were ahead of their time, yet in their work they were also looking to recover a past that never existed. For Griffith, the growing industrial and technological power of the twentieth-century was not attributable to its ingenuity and vast natural resources, but to the innate qualities of its ‘folk’ – a people always in danger of losing its soul to progress and modernity.

*

David Wark Llewelyn Griffith, as his full name suggests, was of Welsh descent. He was born in 1875 and raised on a farm in Kentucky. His father, Jacob ‘Roaring Jake’ Griffith, had been a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Confederate army, both wounded and decorated during the Civil War. David Griffith received little formal education, but, as a boy, he was told stories of the war and the antebellum south by his father, and devoured the popular literature of his day. We can attribute Griffith’s racism to the prevailing attitudes of the ‘Jim Crow’ south, as embodied by his father, and his populist story-telling instincts to his childhood reading; but are any traces of his ‘Welsh’ connections discernible in his work? No reference is made to the European ancestry of the white characters in The Birth of a Nation. It is ostensibly a story about American identities. Yet there are parallels that can be drawn between cultural attitudes regarding the past that are to be found, to this day, in the American south and Wales.

Southerners and the Welsh have similarly maintained deeply ambivalent relationships with the nation states within which they have been historically subsumed. For both Wales and the Deep South the claim of nationhood has been a cultural construct – though in no sense invalid for being so – that has been a point of resistance against harsh political realities. Both peoples were burdened throughout the last century with a pained sense of having lost their birth-right to self-determination, and often seemed to revel in the self-pity of the ‘lost cause’ – one that was always doomed to fail but which nevertheless was prosecuted with a glorious, even poetic, dash and spirit. There is something in Griffith’s evocation of a bucolic, agrarian antebellum south, in his depiction of a glorious-in-defeat Confederacy, and in his celebration of the rebel spirit of southerners reasserted during Reconstruction; that speaks not only of a ‘southern’ view of American history, but also of how the Welsh regard their past. Of course, the majority of southerners, and Welsh, no longer cling to such backward-looking notions of their national identities, yet there are many, in both cultures, who remain steadfast in their sense of a historical betrayal of a former ‘folk innocence’ stampeded by industrialisation, colonialism and the centralising of power within the nation state. That is not to say that there were no injustices perpetrated on the south, or Wales, at different points in their histories; rather that a nurtured sense of past injustices is not a sound basis for national or cultural self-identification.

Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation is based on two Thomas Dixon novels, The Leopard’s Spots (1902) and The Clansman (1905). The film was first shown as The Clansman in Los Angeles on February 8th 1915, but by the time the film received its east-coast premiere at the Liberty Theatre, New York, on March 3rd it had been retitled by Griffith himself, reportedly at Dixon’s suggestion. The film comprises two halves. The first part deals with the outbreak of the Civil War and concludes with the surrender of Robert E. Lee at Appomatox Courthouse. The second part concerns the period of Reconstruction, particularly the temporary post-war acquisition of political power by former slaves and its ramifications. The film’s narrative is refracted, almost entirely, through the experiences of two families who are related to each other – the Stonemans from the north and the Camerons from the south. The outbreak of civil war in part one disrupts a happy family get-together and scuppers the chance of romance between cousins Ben Cameron and Elsie Stoneman (played by the incomparable Lilian Gish). In the second half the cousins are reunited in marriage as the family, and the nation, finally reunites and heals.

The obvious message of both Dixon’s book and Griffith’s film adaptation is that the root causes of the civil war lie not with the iniquities of the slave trade, nor with northern plans to centralise power within the federal government, but with the political machinations of abolitionists and the mere presence of black slaves in America. One of the chief villains of the film is ‘radical leader’ Congressman Austin Stoneman, who is clearly based on the former House of Representatives leader Thaddeus Stevens. In Griffith’s film, the sole motivation for Stoneman/Stevens in aiding the anti-slavery cause is his sexual desire for his ambitious and manipulative ‘mulatto’ house maid – a slur on the real-life Lydia Hamilton Smith. Throughout Griffith’s film the calumny of the ‘lustful negro’ is reified and reimagined. In one devastating scene, the Cameron’s youngest daughter ‘Little Sister’ is pursued through a pine wood by Gus, a black soldier of the occupying federal army. He intends to rape her but rather than submit to him, the girl commits suicide by throwing herself from a cliff top. The would-be rapist Gus is later lynched for this crime by the Ku Klux Klan.

The climax of the film comes with another attempted rape, this time of Elsie by a black Lieutenant-Governor, personally appointed by Stoneman/Stevens. Griffith frequently and disturbingly elides black sexuality with black political power so that the enfranchisement of former slaves is presented as an inevitable precursor to miscegenation. The sexual mores and political aspirations of whites, with the single exception of Stoneman/Stevens, are presented in the film as ‘pure’ as the white of a Klansman’s robe. One of the final, terrible images of the film shows black voters being terrified from entering temporary election booths by mounted and hooded Ku Klux Klan. It is one of the most potent depictions of fascism to be found anywhere in cinema.

Which returns us to the question of whether we can, or should, separate Griffith’s formidable cinematic technique from the racist ideology of The Birth of a Nation. A close analysis of the film’s text reveals that the former is always in service of the latter. In our age of computer generated collapsing stars and fire-breathing dragons it is easy to forget that the greatest special effect the cinema possesses is the close-up – the director’s ultimate tool of control through which he can intensely focus the gaze of the audience on a single visual detail. Griffith pioneered the close-up because he fully understood the power of semiotics before the term was invented. The close-up enabled him to weave within his films a lexicography of symbols, each conjuring a range of conscious and unconscious associations that produce the binary extremes of fear and innocence, despair and hope, cynicism and idealism that are the stock-in-trade oversimplifications of the ideologue.

Griffith’s use of cross-cut editing brought a thrilling dynamism to cinema. In early filmmaking the camera remained rather static, simply recording whatever was going on in front of its lens, very often in single takes. The cross-cut edit, as pioneered by Griffith, moved the action along, built suspense and stirred excitement. As film critic James Agee observed at the time:

To watch [Griffith’s] work is like being witness to the beginning of melody, or the first conscious use of the lever or the wheel; the emergence, coordination, and first eloquence of language; the birth of an art: and to realize that this is all the work of one man.

Yet Griffith’s cross-cut editing does not operate simply as a means of pacing the film, or providing it with pulsating rhythm – it also enables him to manipulate the sympathies of his audience, perhaps against their better judgement. Take, for instance, the penultimate scene of the film in which the Stoneman-Cameron family is besieged inside a log-cabin by a crazed gang of black federal soldiers intent on murdering them. This siege, complete with swooning women fearing rape, is cross cut with a cavalry charge of Ku Klux Klan members racing to rescue them. These Klan members are presented more like the Teutonic knights of medieval legend than the paramilitary racist thugs history knows them to be. Griffith’s cinematic innovations also included commissioning a full-length score to accompany his silent masterpiece – featuring the music of Wagner among others. Perhaps a tip of the hat from one master-manipulator to another?

Contemporary reaction to The Birth of a Nation in America was divided, to say the least. The NAACP tried to get it banned because of its inflammatory stereotyping. When riots broke out in Boston, Philadelphia and other major U.S. cities following screenings of the film, the cities of Chicago, Denver, Kansas City, Minneapolis, Pittsburgh and St. Louis all refused to allow the film to open. Despite, or perhaps because of the controversy, the film was a huge commercial success. Its box office records would only be eclipsed by another civil war epic, with its own questionable racial politics, Gone with the Wind (1939). While some critics, such as Agee, saluted Griffith’s technical achievements and creative ambition, there were others who rejected its crude racism. Frances Hackett, writing in the New Republic, argued that Thomas Dixon had merely ‘displaced his own malignity onto the Negro’. A New York Globe editorial thundered that the film was an insult to the legacy of George Washington.

The most controversial review of the film, however, came from President Woodrow Wilson who, following a White House screening of the film, reportedly described the film as ‘like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.’ The line is possibly apocryphal, and a Presidential aide quickly dashed off a letter to the NAACP denying Wilson’s remarks. Yet although we cannot be certain as to whether the president offered such a sympathetic judgement on The Birth of a Nation, one of the film’s intertitles features a quote from Wilson’s A History of the American People, in which he wrote that during reconstruction, ‘In the villages [of the south] the negroes were the officeholders, men who knew nothing of the uses of authority, except its insolences.’

*

The lessons of The Birth of a Nation are sharply relevant to our current moment. Our culture is one that is becoming defined by technological advances that offer us the thrills of spectacle whilst masking the ideological underpinnings of cultural product in a haze of unthinking wonderment. In the West we face a range of complex political and social questions posed by the effects of globalisation, capitalist exploitation and mass-migration that are being defined as questions of race by lazy media organisations unable to respond with nuance and insight in a climate of 24-hour rolling news coverage that cannot settle in fear of losing viewers. Griffith’s work is a warning to us all of the dangers of using innovative technical media as the messenger of the comfy old canards of a reassuringly innocent, though entirely mythical, past. The crucial question the film poses for us now is this – Are we so different from that audience of 1915, do we applaud the notional progress of technological advance at the expense of forgetting our own histories?