Gary Raymond revisits one of Ken Russell’s most controversial films, The Devils, and questions the rights of a censor to curtail the artistic vision.

In May of 1995 Alex Cox presented to the British public the most complete version of Ken Russell’s The Devils available since the early seventies as part of his ‘Forbidden Cinema’ season on BBC 2. Now, seventeen years later, an equally respectful cut makes it for the first time to DVD. Generally regarded as a masterpiece of British film-making, The Devils has a history of censorious turmoil as well as misrepresentation and misunderstanding. As Father Gene Phillips S.J. (Consultant to the New York Catholic organisation, The Legion of Decency at the time of the film’s release) points out in one of the documentaries that accompany this DVD, that the film depicts blasphemy, but is not in itself blasphemous. To the educated that much is obvious, but Russell’s ‘only political film’ has suffered for forty years at the hands of censors as well as Hollywood owners who have always felt the film strayed too far from their own stringent attempts to morally codify the parameters of art.

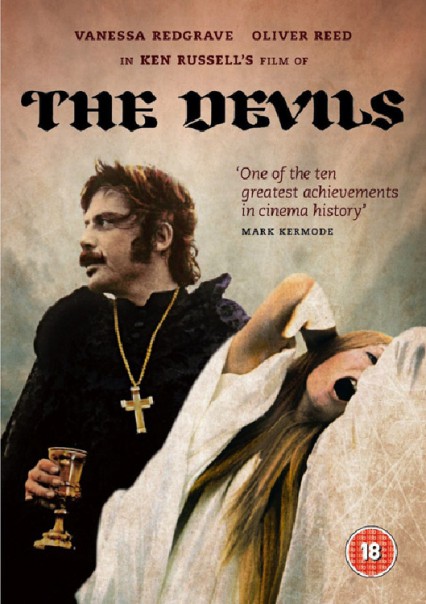

BFI

Directed by Ken Russell

Starring: Oliver Reed, Vanessa Redgrave,

Gemma Jones, Dudley Sutton

The story, as told in John Whiting’s 1960 play The Devils, and Aldous Huxley’s sumptuous documentary-

Reed’s Grandier is a complex figure, and his narrative arc is one that leads to ultimate redemption. His association to Christ, symbolically outside the narrative, as well as inside it to those who obsess over him, is a magnificently bold statement by Russell. If Jesus’ redemption is in annihilation then so is everyone’s, and the brutal torture and execution of Grandier at the stake, as he offers his condemners mercy, is a lesson to anyone who thought the puerile masochism of nonsense like Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ was a significant statement on the nature of faith and religion.

Grandier is condemned at the point we see the change in him. He is delivered from a life of carnal preoccupations by the love of a pure and righteous woman, Madeleine, to whom he becomes married in the hope of finally reaching God through love and sacrament (the historical Grandier wrote a long treatise on how there is no Biblical requisite dictating that Priests should not marry in 1630, a document from which Russell quotes in his script). As Grandier is delivered, however, the plot orchestrating his downfall is driving Loudon in the other direction. In particular those confined to the Ursuline convent in the city and their Mother Superior, Sister Jeanne of the Angels. The modern interpretation of events, from Alexandre Dumas, père, onwards, is that Sister Jeanne, having become obsessed with Grandier, accused him of possessing her with devils after he refused the convent’s invitation for him to become their Father Confessor. Russell’s dream-

Vanessa Redgrave, also in the performance of her life as the hunch-

as the hunch-backed repressed – indeed demented

– Sister Jeanne”

As history documents, Sister Jeanne, after her bitter accusation, was subjected to heinous bouts of physical abuse at the hands of Richelieu’s clerics out for Grandier’s head. Her primary examination at the hands of Inquisitor Father Barre (played in the film as a kind of Nazi pervert by Michael Gothard) was described by Huxley as no less than ‘rape in a public lavatory’. Ken Russell’s film has this description very much in mind when depicting these initial events. The result of the torture of Sister Jeanne was that the other inhabitants of the convent, made up not of devout young girls dedicating themselves to God, but of ‘noble women who have embraced the monastic life because there was not enough money at home to provide them with dowries, or they were unmarriageable because ugly or a burden to the family’, also accused Grandier of infesting their sanctuary with demons and devils. Mark Kermode’s curiously dated documentary Hell on Earth, which can be found on the second disc of this DVD production, spends a little time on the psychological connotations of the ‘possessions’ and the months of public exorcisms that followed. Mass hysteria is the most plausible explanation, caused by the releasing of a valve of almost unimaginable tension in a group of harshly repressed young women, most of who were discarded by their fathers before being forced into man-

The exorcisms themselves appeared to have been little more than orgiastic theatrics that not only helped destroy Grandier (who was cleared once of the accusations in a court-

It is the climax of Ken Russell’s wild visualisation of these public exorcisms that proved the downfall of the movie where its financiers and the censors-

In this welcomed release on DVD of Russell’s masterpiece, the scene now known simply as ‘The Rape of Christ’ is still missing, and with Russell’s death last year doing nothing to rescind the exclusion (which is the will of the American owners; Russell himself was always vehement in his support of the inclusion of the scene) it seems this may be the closest the public will get to a respectful edit of Russell’s grand vision. That you can see ‘The Rape of Christ’ in close to its entirety in the included Hell on Earth documentary renders this frustrating set of circumstances all the more ludicrous.

One of the problems may have always been that Ken Russell’s telling of this true story is highly stylised. With an enormous set designed by a young Derek Jarman, the cinematography of David Watkins, and the chaotic, visceral compositions of Peter Maxwell Davies, Russell assembled one of the finest teams of visionary film-

The public reaction at the time to The Devils included the picketing of cinemas and some exemplary critical hatchet jobs. It was perhaps understandable given that its release came at the beginning of a decade the end of which saw the banning of The Life of Brian, a rather tame satire in comparison. Ken Russell’s film is still a harrowing experience, despite its immense rewards. Perhaps the other famous cut scene, from the end of the film, where Sister Jeanne masturbates with the charred femur of Grandier as the city walls are blown down, is still taking the grief of Bob Peck in Edge of Darkness (which did not cause controversy for another fifteen years) to extremes of debauched poignancy. But who are we to curtail genius, the product of which this film most certainly is? Who gives the right to the American religious censors to snip and claw at it? The film, and this DVD, the most important release of recent times, stands tall. But it also stands wounded by ignorance. That it is available at all is something to be grateful for, but always remember that this release also stands as a testament to the power of ignorance over art.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.

Enjoyed this article? Support our writers directly by buying them a coffee and clicking this link.